Grant Takes Command

Printed Page 450

Section Chronology

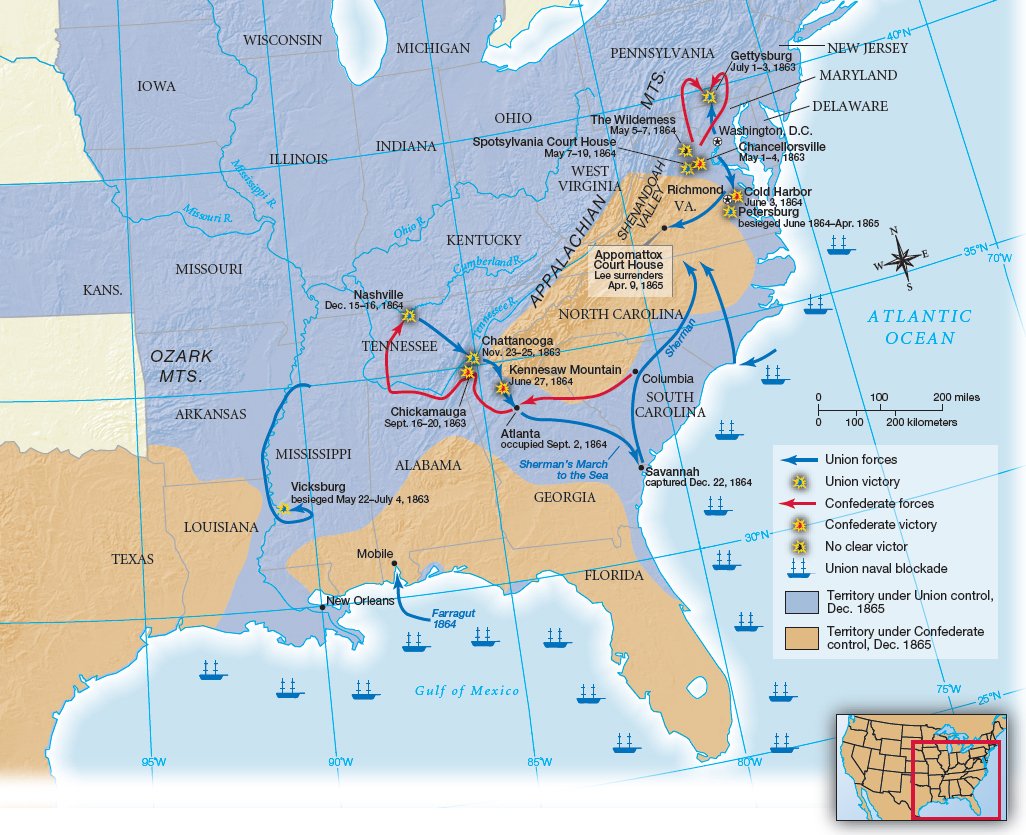

In September 1863, Union general William Rosecrans placed his army in a dangerous situation in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he had retreated after defeat at the battle of Chickamauga (Map 15.3). Rebels surrounded the disorganized bluecoats and threatened to starve them into submission. Grant, now commander of Union forces between the Mississippi River and the Appalachians, arrived in nearby Chattanooga in October. Within weeks, he opened an effective supply line, broke the siege, and routed the Confederate army. The victory at Chattanooga on November 25 opened the door to Georgia. In March 1864, Lincoln asked Grant to come east to become the general in chief of all Union armies.

In Washington, General Grant implemented his grand strategy for a war of attrition. He ordered a series of simultaneous assaults from Virginia all the way to Louisiana. Two actions proved particularly significant. In one, General William Tecumseh Sherman, whom Grant appointed his successor to command the western armies, plunged southeast toward Atlanta. In the other, Grant, who took control of the Army of the Potomac, went head-to-head with Lee in Virginia in May and June of 1864.

The fighting between Grant and Lee was particularly savage. At the battle of the Wilderness, where a dense tangle of forest often made it impossible to see more than ten paces, the armies pounded away at each other until approximately 18,000 Yankees and 11,000 rebels had fallen. At Spotsylvania Court House, frenzied men fought hand to hand for eighteen hours in the rain. One veteran remembered men “piled upon each other in some places four layers deep, exhibiting every ghastly phase of mutilation.” Spotsylvania cost Grant another 18,000 casualties and Lee 10,000. Grant kept moving and attacked Lee again at Cold Harbor, where he suffered 13,000 additional casualties to Lee’s 5,000.

Twice as many Union soldiers as rebel soldiers died in four weeks of fighting in Virginia, but because Lee had only half as many troops as Grant, his losses were equivalent to Grant’s. Grant knew that the South could not replace the losses. Moreover, the campaign carried Grant to the outskirts of Petersburg, just south of Richmond, where he abandoned the costly tactic of the frontal assault and began a siege that immobilized both armies and dragged on for nine months.

Simultaneously, Sherman invaded Georgia. Skillful maneuvering, constant skirmishing, and one pitched battle, at Kennesaw Mountain, brought Sherman to Atlanta, which fell on September 2. Intending to “make Georgia howl,” Sherman marched out of Atlanta on November 15 with 62,000 battle-hardened veterans, heading for Savannah, 285 miles away on the Atlantic coast. One veteran remembered, “[We] destroyed all we could not eat, stole their niggers, burned their cotton & gins, spilled their sorghum, burned & twisted their R. Roads and raised Hell generally.” Sherman's March to the Sea aimed at destroying the will of white Southerners to continue the war. A few weeks earlier, General Philip H. Sheridan had carried out his own scorched-earth campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. When Sherman’s troops entered an undefended Savannah in mid-December, the general telegraphed Lincoln that he had “a Christmas gift” for him. A month earlier, Union voters had bestowed on the president an even greater gift.

Sherman’s March to the Sea

Military campaign from September through December 1864 in which Union forces under General William Tecumseh Sherman marched from Atlanta, Georgia, to the coast at Savannah. Carving a path of destruction as it progressed, Sherman’s army aimed at destroying white Southerners’ will to continue the war.

Military campaign from September through December 1864 in which Union forces under General William Tecumseh Sherman marched from Atlanta, Georgia, to the coast at Savannah. Carving a path of destruction as it progressed, Sherman’s army aimed at destroying white Southerners’ will to continue the war.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

Why did both the Union and the Confederacy consider control of the border states crucial?

Why did each side expect to win?

How did each side fare in the early years of the war?

How did the war for union become a fight for black freedom?

What problems did the Confederacy face at home?

How did the war affect the economy and politics of the North?

How did the Union finally win the war?

Conclusion: In what ways was the Civil War a “Second American Revolution”?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.

Major Battles of the Civil War, 1863–1865

> Major Battles of the Civil War, 1863–1865

| May 1–4, 1863 | Battle of Chancellorsville |

| July 1–3, 1863 | Battle of Gettysburg |

| July 4, 1863 | Fall of Vicksburg |

| September 16–20, 1863 | Battle of Chickamauga |

| November 23–25, 1863 | Battle of Chattanooga |

| May 5–7, 1864 | Battle of the Wilderness |

| May 7–19, 1864 | Battle of Spotsylvania Court House |

| June 3, 1864 | Battle of Cold Harbor |

| June 27, 1864 | Battle of Kennesaw Mountain |

| September 2, 1864 | Fall of Atlanta |

| November–December 1864 | Sheridan sacks Shenandoah Valley Sherman’s March to the Sea |

| December 15–16, 1864 | Battle of Nashville |

| December 22, 1864 | Fall of Savannah |

| April 2–3, 1865 | Fall of Petersburg and Richmond |

| April 9, 1865 | Lee surrenders at Appomattox Court House |