Why did the United States largely abandon its isolationist foreign policy in the 1890s?

Printed Page 598

CHRONOLOGY

1894

- – President Grover Cleveland nixes attempt to annex Hawai’i.

1895

- – Cleveland enforces Monroe Doctrine in border dispute between British Guiana and Venezuela.

1898

- – U.S. battleship Maine explodes in Havana harbor.

- – Congress declares war on Spain.

- – U.S. Navy destroys Spanish fleet in Manila Bay, the Philippines.

- – U.S. troops defeat Spanish forces in Cuba.

- – Treaty of Paris ends war with Spain.

- – United States annexes Hawai’i.

1899–1900

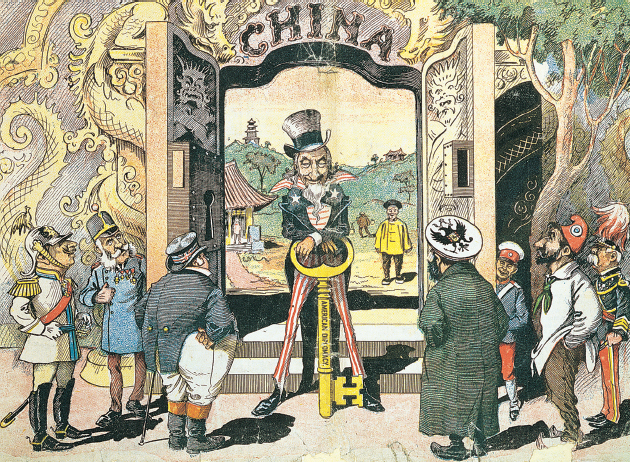

- – Secretary of State John Hay enunciates Open Door policy in China.

- – Boxer uprising in China.

1901

- – European powers impose Boxer Protocol on Chinese government.

THROUGHOUT MUCH OF THE SECOND HALF of the nineteenth century, U.S. interest in foreign policy took a backseat to territorial expansion in the American West. The United States fought the Indian wars while European nations carved out empires in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the United States pursued a foreign policy consisting of two currents — isolationism and expansionism. Although the determination to remain detached from European politics had been a hallmark of U.S. foreign policy since the nation’s founding, Americans simultaneously believed in manifest destiny — the “obvious” right to expand the nation from ocean to ocean. With its own inland empire secured, the United States looked outward. Determined to protect its sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere and to expand its trading in Asia, the nation moved away from isolationism and toward a more active role on the world stage that led to intervention in China’s Boxer uprising and war with Spain.