Family and Religion

From dawn to dusk, slaves worked for the master, but at night and all day Sunday and usually Saturday afternoon, slaves were left largely to themselves. Bone tired perhaps, they nonetheless used the time to develop what mattered most to them. Over the generations, they created a community and a culture of their own that sustained them.

Slavery was a severe assault on the slave family. African Americans were bought and sold at public auctions and at private sales. Between 1820 and 1860, while some one million slaves entered the interstate slave trade that fed labor to the booming Cotton South, perhaps twice as many slaves were sold locally. Every slave dreaded the appearance of a slave trader at the gate of the plantation. Falling into the hands of a trader meant separation from family, probably for life, and a new existence under an unknown master.

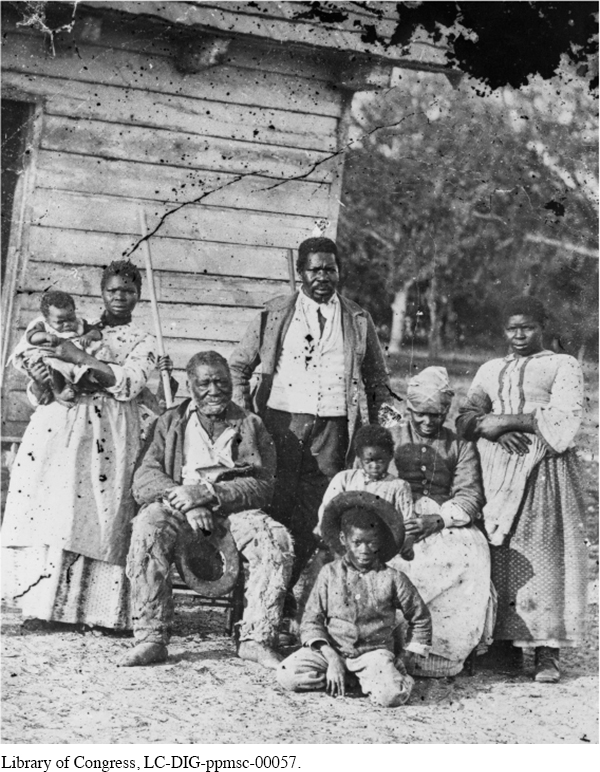

Though severely battered, the black family survived slavery. Young men and women in the quarter fell in love, married, and set up housekeeping in cabins of their own. But no laws recognized slave marriage, and therefore no master was legally obligated to honor the bond. While plantation records show that some slave marriages were long-lasting, the massive deportation associated with the Second Middle Passage and local sales destroyed hundreds of thousands of slave families. [[LP Photo: P13.06 “Family Outside Cabin, 1862”/

In 1858, a slave named Abream Scriven wrote to his wife, who lived on a neighboring plantation in South Carolina. “My dear wife,” he began, “I take the pleasure of writing you . . . with much regret to inform you I am Sold to man by the name of Peterson, a Treader and Stays in New Orleans.” Before he left for Louisiana, Scriven asked his wife to “give my love to my father and mother and tell them good Bye for me. And if we do not meet in this world I hope to meet in heaven. . . . My dear wife for you and my children my pen cannot express the griffe I feel to be parted from you all.” He closed with words no master would have permitted in a slave’s marriage vows: “I remain your truly husband until Death.” The letter makes clear Scriven’s love for and commitment to his family; it also demonstrates slavery’s massive assault on family life in the quarter.

Masters sometimes permitted slave families to work on their own, “overwork,” as it was called. In the evenings and on Sundays, they tilled gardens, raised pigs and fowl, and chopped wood, selling the products in the market for a little pocket change. “Den each fam’ly have some chickens and sell dem and de eggs and maybe go huntin’ and sell de hides and git some money,” a former Alabama slave remembered. “Den us buy what am Sunday clothes with dat money, sech as hats and pants and shoes and dresses.” Slave children remembered the extraordinary efforts their parents made to sustain their families, and they held them in high esteem.

Religion also provided slaves with a refuge and a reason for living. In the nineteenth century, evangelical Baptists and Methodists had great success in converting slaves from their African beliefs. Planters promoted Christianity in the quarter because they believed that the slaves’ salvation was part of the obligation of paternalism; they also hoped that religion would make slaves more obedient. South Carolina slaveholder Charles Colcock Jones, the leading missionary to the slaves, instructed them “to count their Masters ‘worthy of all honour,’ as those whom God has placed over them in this world.” But slaves laughed up their sleeves at such messages. “That old white preacher just was telling us slaves to be good to our masters,” one ex-slave said with a chuckle. “We ain’t cared a bit about that stuff he was telling us ’cause we wanted to sing, pray, and serve God in our own way.”

Meeting in their cabins or secretly in the woods, slaves created an African American Christianity that served their needs, not the masters’. Laws prohibited teaching slaves to read, but a few could read enough to struggle with the Bible. They interpreted the Christian message themselves. Rather than obedience, their faith emphasized justice. Slaves believed that God kept score and that the accounts of this world would be settled in the next. “God is punishing some of them old suckers and their children right now for the way they use to treat us poor colored folks,” one ex-slave declared. But the slaves’ faith also spoke to their experiences in this world. In the Old Testament, they discovered Moses, who delivered his people from slavery, and in the New Testament, they found Jesus, who offered salvation to all. Jesus’ message of equality provided a potent antidote to the planters’ claim that blacks were an inferior people whom God condemned to slavery.

Christianity did not entirely drive out traditional African beliefs. Even slaves who were Christians sometimes continued to believe that conjurers, witches, and spirits possessed the power to injure and protect. Moreover, slaves’ Christian music, preaching, and rituals reflected the influence of Africa, as did many of their secular activities, such as wood carving, quilt making, dancing, and storytelling. But by the mid-nineteenth century, black Christianity had assumed a central place in slaves’ quest for freedom. In the words of one spiritual, “O my Lord delivered Daniel /

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 361