White Supremacy Triumphs

Reconstruction was a massive humiliation to most white Southerners. Republican rule meant intolerable insults: Black militiamen patrolled town streets, black laborers negotiated contracts with former masters, black maids stood up to former mistresses, black voters cast ballots, and black legislators such as James T. Rapier enacted laws. Whites fought back by extolling the “great Confederate cause,” or Lost Cause. They celebrated their soldiers, “the noblest band of men who ever fought,” and by making an idol of Robert E. Lee, the embodiment of the southern gentleman.

But the most important way white Southerners responded to reconstruction was their assault on Republican governments in the South. These Republican governments attracted more hatred than did any other political regimes in American history. The northern retreat from reconstruction permitted southern Democrats to set things right. Taking the name Redeemers, Democrats in the South promised to replace “bayonet rule” (a few federal troops continued to be stationed in the South) with “home rule.” They promised that honest, thrifty Democrats would supplant corrupt tax-and-spend Republicans. Above all, Redeemers swore to save southern civilization from a descent into “African barbarism.” As one man put it, “We must render this either a white man’s government, or convert the land into a Negro man’s cemetery.”

Southern Democrats adopted a multipronged strategy to overthrow Republican governments. First, they sought to polarize the parties around race. They went about gathering all the South’s white voters into the Democratic Party, leaving the Republicans to depend on blacks, who made up a minority of the population in almost every southern state. To dislodge whites from the Republican Party, Democrats fanned the flames of racism. A South Carolina Democrat crowed that his party appealed to the “proud Caucasian race, whose sovereignty on earth God has proclaimed.” Ostracism also proved effective. Local newspapers published the names of whites who kept company with blacks. So complete was the ostracism that one of its victims said, “No white man can live in the South in the future and act with any other than the Democratic party unless he is willing and prepared to live a life of social isolation.”

Democrats also exploited the severe economic plight of small white farmers by blaming it on Republican financial policy. Government spending soared during Reconstruction, and small farmers saw their tax burden skyrocket. “This is tax time,” a South Carolinian reported. “We are nearly all on our head about them. They are so high & so little money to pay with” that farmers were “selling every egg and chicken they can get.” In 1871, Mississippi reported that one-seventh of the state’s land—3.3 million acres—had been forfeited for nonpayment of taxes. The small farmers’ economic distress had a racial dimension. Because few freedmen succeeded in acquiring land, they rarely paid taxes. In Georgia in 1874, blacks made up 45 percent of the population but paid only 2 percent of the taxes. From the perspective of a small white farmer, Republican rule meant that he was paying more taxes and paying them to aid blacks.

If racial pride, social isolation, and financial hardship proved insufficient to drive yeomen from the Republican Party, Democrats turned to terrorism. “Night riders” targeted white Republicans as well as blacks for murder and assassination. Whether white or black, a “dead Radical is very harmless,” South Carolina Democratic leader Martin Gary told his followers.

But the primary victims of white violence were black Republicans. Violence escalated to an unprecedented ferocity on Easter Sunday in 1873 in tiny Colfax, Louisiana. The black majority in the area had made Colfax a Republican stronghold until 1872, when Democrats turned to intimidation and fraud to win the local election. Republicans refused to accept the result and occupied the courthouse in the middle of the town. After three weeks, 165 white men attacked. They overran the Republicans’ defenses and set the courthouse on fire. When the blacks tried to surrender, the whites murdered them. At least 81 black men were slaughtered that day. Although the federal government indicted the attackers, the Supreme Court ruled that it did not have the right to prosecute. And since local whites would not prosecute neighbors who killed blacks, the defendants in the Colfax massacre went free.

> CONSIDER CAUSE

AND EFFECT

What factors led to the demise of Reconstruction, and which played the most important role?

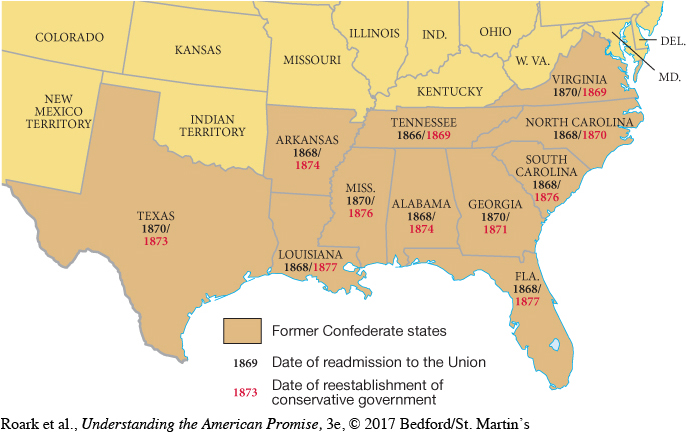

Even before adopting the all-out white supremacist tactics of the 1870s, Democrats had taken control of the governments of Virginia, Tennessee, and North Carolina. The new campaign brought fresh gains. The Redeemers retook Georgia in 1871, Texas in 1873, and Arkansas and Alabama in 1874. As the state election approached in Mississippi in 1876, Governor Adelbert Ames appealed to Washington for federal troops to control the violence, only to hear from the attorney general that the “whole public are tired of these annual autumnal outbreaks in the South.” Abandoned, Mississippi Republicans succumbed to the Democratic onslaught in the fall elections. By 1876, only three Republican state governments survived in the South (Map 16.3). [[LP Map: M16.03 The Reconstruction of the South – MAP ACTIVITY/

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 462

Section Chronology