An Election and a Compromise

The year 1876 witnessed one of the most tumultuous elections in American history. The election took place in November, but not until March 2 of the following year did the nation know who would be inaugurated president on March 4. Sixteen years after Lincoln’s election, Americans feared that a presidential election would again precipitate civil war.

The Democrats nominated New York’s governor, Samuel J. Tilden, who immediately targeted the corruption of the Grant administration and the “despotism” of Republican reconstruction. The Republicans put forward Rutherford B. Hayes, governor of Ohio. Privately, Hayes considered “bayonet rule” a mistake but concluded that waving the bloody shirt remained the Republicans’ best political strategy.

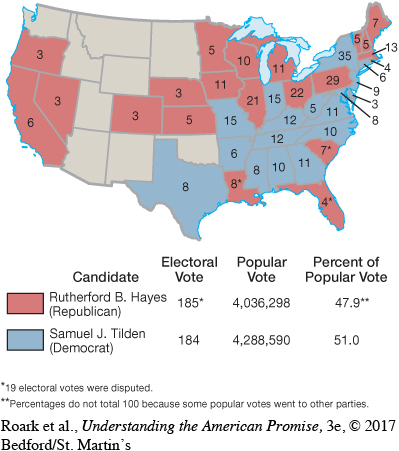

On election day, Tilden tallied 4,288,590 votes to Hayes’s 4,036,298. But in the all-important electoral college, Tilden fell one vote short of the majority required for victory. The electoral votes of three states—South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida, the only remaining Republican governments in the South—remained in doubt because both Republicans and Democrats in those states claimed victory. To win, Tilden needed only one of the nineteen contested votes. Hayes had to have all of them.

Congress had to decide who had actually won the elections in the three southern states and thus who would be president. The Constitution provided no guidance for this situation. Moreover, Democrats controlled the House, and Republicans controlled the Senate. Congress created a special electoral commission to arbitrate the disputed returns. All of the commissioners voted their party affiliation, giving every state to the Republican Hayes and putting him over the top in electoral votes (Map 16.4). [[LP Map: M16.04 The Election of 1876/

Some outraged Democrats vowed to resist Hayes’s victory. Rumors flew of an impending coup and renewed civil war. But the impasse was broken when negotiations behind the scenes resulted in an informal understanding known as the Compromise of 1877. In exchange for a Democratic promise not to block Hayes’s inauguration and to deal fairly with the freedmen, Hayes vowed to refrain from using the army to uphold the remaining Republican regimes in the South and to provide the South with substantial federal subsidies for railroads.

Stubborn Tilden supporters bemoaned the “stolen election” and damned “His Fraudulency,” Rutherford B. Hayes. Old-guard Radicals such as William Lloyd Garrison denounced Hayes’s bargain as a “policy of compromise, of credulity, of weakness, of subserviency, of surrender.” But the nation as a whole celebrated, for the country had weathered a grave crisis. The last three Republican state governments in the South fell quickly once Hayes abandoned them and withdrew the U.S. Army. Reconstruction came to an end.

> QUICK REVIEW

How did the Supreme Court undermine Reconstruction?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 464

Section Chronology