ANALYZING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE: Custer’s Last Stand

ANALYZING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

Custer’s Last Stand

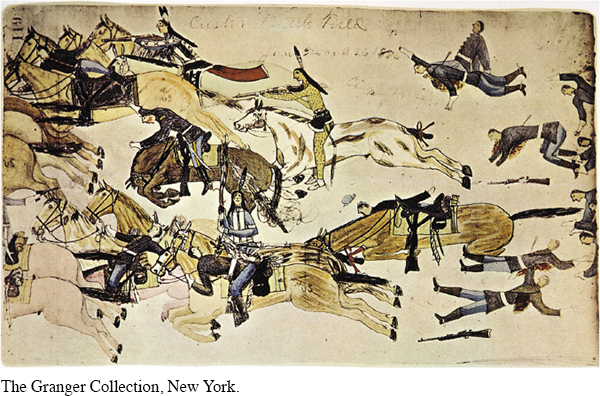

Only one American soldier survived the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Yet many Indians remembered the battle and depicted it in illustrations. In this pictograph, Amos Bad Heart Bull, an Oglala Sioux from the Pine Ridge Reservation, dramatized the battle at the river the Indians called the Greasy Grass. Although the artist was only seven years old in 1876 when the battle occurred, he based his pictures on the recollections of his uncle and other Oglala elders. Crazy Horse ritually prepared for battle by painting hailstones on his body, wearing a small stone tied behind one ear, and placing a single eagle feather in his hair. Featured at the center of the pictograph, he can be identified by his unique war paint. According to one Arapaho warrior who fought beside him, Crazy Horse “was the bravest man he ever saw.” [[LP Photo: P17.04 Crazy Horse at the Little Big Horn, Amos Bad Heart Bull – AHE Illustration/

Even at the time, Indian and white participants interpreted events differently. One of the soldiers cut off from Custer’s group feared for his life as he heard “wild victory dances” coming from the Lakota camp. But what he heard, according to a Cheyenne warrior named Wooden Leg, were the songs of the Lakota and Cheyenne, mourning their sons, husbands, and fathers. The soldier, who huddled on Reno Hill praying throughout the night, not only survived but lived until 1950, making him the only white survivor of “Custer’s Last Stand.”

Many of the battle depictions by whites were little more than romantic idealism, with Custer on horseback leading a valiant charge. In this 1889 lithograph of the battle, Custer and his men are shown dismounted, firing at Indians on horseback. A much more accurate portrayal than many of the others in circulation at the time, the lithograph shows how badly Custer was outnumbered when he divided his forces and led a contingent into the largest gathering of Indians ever to meet on the plains. [[LP Photo: P17.05 The Battle of Little Big Horn, 1889 – AHE Illustration/

Popular portrayals of the battle proliferated. Buffalo Bill Cody staged a reenactment of the battle as a centerpiece of his Wild West show. At least one poster from the 1880s shows a Custer who looks remarkably like Buffalo Bill. Both men were famous for their long blonde hair. Remarkably, Custer did not lose his scalp, as did most of his men. By all accounts, Custer’s body was not mutilated (except for one fingertip and a pierced eardrum). Why did the Indians not take his scalp as a trophy? In large part, the answer has changed as Custer’s fortunes with historians and the public have waxed and waned. At the time of his death and for decades after, Custer was viewed as a hero and martyr. Writers explained that his Indian foes respected the man they called Phuska, or Long Hair, and refused to take his scalp. A century later, Custer’s reputation sank to a low ebb as historians began to focus on the Indians’ experience in the West. One author speculated that Custer, who was balding by 1879, was spared because from a warrior’s point of view his scalp made a poor trophy.

Questions for Analysis

ANALYZE THE EVIDENCE: Compare the portrayals of Custer’s Last Stand. What strikes you about the Indian version in relationship to the Anglo lithograph?

RECOGNIZE VIEWPOINTS: Who is the center of focus for the Indians? Who for the Anglos? How does this reflect the two sides’ different interpretations of this dramatic encounter?

CONSIDER THE CONTEXT: In what ways does the comparison of the depictions of the Battle of the Little Big Horn point to conflicting interpretations of the larger history of the American West?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 478

Section Chronology