Haymarket and the Specter of Labor Radicalism

While the AFL and the Knights of Labor competed for members, more radical labor groups, including socialists and anarchists, believed that reform was futile and called instead for social revolution. Both the socialists and the anarchists, sensitive to criticism that they preferred revolution in theory to improvements here and now, rallied around the popular issue of the eight-hour day.

Since the 1840s, labor had sought to end the twelve-hour workday, which was standard in industry and manufacturing. By the mid-1880s, it seemed clear to many workers that labor shared too little in the new prosperity of the decade, and pressure mounted for the eight-hour day. Labor championed the popular issue and launched major rallies in cities across the nation. Supporters of the movement set May 1, 1886, as the date for a nationwide general strike in support of the eight-hour workday.

All factions of the labor movement came together in Chicago on May Day. A group of labor radicals led by anarchist Albert Parsons, a Mayflower descendant, and August Spies, a German socialist, spearheaded the eight-hour movement in Chicago. Chicago’s Knights of Labor rallied to the cause even though Powderly and the union’s national leadership, worried about the increasing activism of the rank and file, refused to endorse the movement for shorter hours. Gompers was also on hand to lead the city’s trade unionists, although he privately urged the AFL assemblies not to participate in the general strike.

The cautious labor leaders in their frock coats and starched shirts stood in sharp contrast to the dispossessed workers out on strike across town at Chicago’s huge McCormick reaper works. There strikers watched helplessly as the company brought in strikebreakers to take their jobs and marched the “scabs” to work under the protection of the Chicago police and security guards supplied by the Pinkerton Detective Agency. Cyrus McCormick Jr., son of the inventor of the mechanical reaper, viewed labor organization as a threat to his power as well as to his profits; he was determined to smash the union.

During the May Day rally, 45,000 workers paraded peacefully down Michigan Avenue in support of the eight-hour day. Many sang what had become the movement’s anthem:

We want to feel the sunshine;

We want to smell the flowers,

We’re sure that God has willed it,

And we mean to have eight hours.

Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest,

Eight hours for what we will!

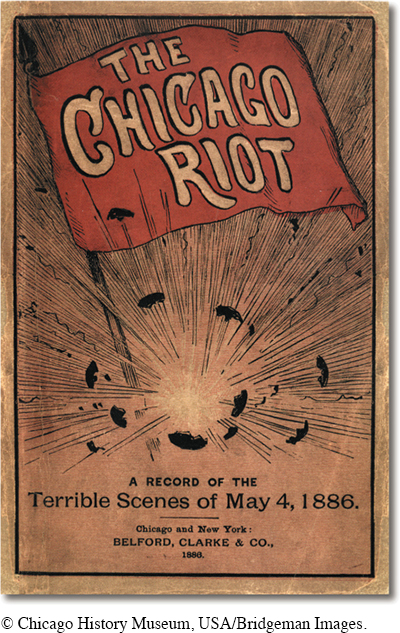

Trouble came two days later, when strikers attacked strikebreakers outside the McCormick works and police opened fire, killing or wounding six men. Angry radicals urged workers to “arm yourselves and appear in full force” at a rally in Haymarket Square.[[LP Photo: P19.06 “The Chicago Riot” – VISUAL ACTIVITY/

> PLACE EVENTS

IN CONTEXT

Why were so many of the labor struggles of the late nineteenth century marked by violence?

On the evening of May 4, the turnout at Haymarket was disappointing. No more than two or three thousand gathered in the drizzle to hear Spies, Parsons, and the other speakers. Mayor Carter Harrison, known as a friend of labor, mingled conspicuously in the crowd, pronounced the meeting peaceable, and went home to bed. Sometime later, police captain John “Blackjack” Bonfield marched his men into the crowd, by now fewer than three hundred people, and demanded that it disperse. Suddenly, someone threw a bomb into the police ranks. After a moment of stunned silence, the police drew their revolvers. “Fire and kill all you can,” shouted a police lieutenant. When the melee ended, seven policemen and an unknown number of others lay dead. An additional sixty policemen and thirty or forty civilians suffered injuries.

News of the “Haymarket riot” provoked a nationwide convulsion of fear, followed by blind rage directed at anarchists, labor unions, strikers, immigrants, and the working class in general. Eight men, including Parsons and Spies, went on trial in Chicago. “Convict these men,” thundered the state’s attorney, Julius S. Grinnell, “make examples of them, hang them, and you save our institutions.” Although the state could not link any of the defendants to the Haymarket bombing, the jury nevertheless found them all guilty. Four men hanged, one committed suicide, and three received prison sentences.

The bomb blast at Haymarket had lasting repercussions. To commemorate the death of the Haymarket martyrs, labor made May 1 an annual international celebration of the worker. But the Haymarket bomb, in the eyes of one observer, proved “a godsend to all enemies of the labor movement.” It effectively scotched the eight-hour-day movement and dealt a blow to the Knights of Labor. With the labor movement everywhere under attack, many skilled workers turned to the AFL. Gompers’s narrow economic strategy made sense at the time and enabled one segment of the workforce—the skilled—to organize effectively and achieve tangible gains.

> QUICK REVIEW

What were the long-term effects of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Haymarket bombing of 1886?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 542

Section Chronology