Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and the Movement for Woman Suffrage

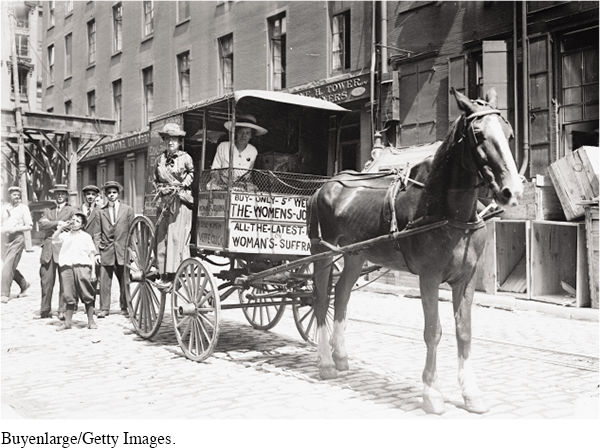

Unlike the WCTU, the organized movement for woman suffrage remained small and relatively weak in the late nineteenth century. In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her ally, Susan B. Anthony, launched the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) demanding the vote for women (see chapter 18). A more conservative group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), formed the same year. Composed of men as well as women, the AWSA believed that women should stick with the Republican Party and make suffrage the Sixteenth Amendment. Their optimism proved misplaced. [[LP Photo: P20.06 Women’s Suffrage Campaigners/

By 1890, the split had healed, and the newly united National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) launched campaigns on the state level to gain the vote for women. Twenty years had made a great change. Woman suffrage, though not yet generally supported, was no longer considered a crackpot idea, thanks in part to the WCTU’s support of the “home protection” ballot. The NAWSA honored Elizabeth Cady Stanton by electing her its first president, but Susan B. Anthony, who took the helm in 1892, emerged as the leading figure in the new united organization.

Stanton and Anthony, both in their seventies, were coming to the end of their public careers. Since the days of the Seneca Falls woman’s rights convention, they had worked for reforms for their sex, including property rights, custody rights, and the right to education and gainful employment. But the prize of woman suffrage still eluded them. Suffragists won victories in Colorado in 1893 and Idaho in 1896. One more state joined the suffrage column in 1896 when Utah entered the Union. But women suffered a bitter defeat in a California referendum on woman suffrage that same year. Never losing faith, Anthony remarked in her last public appearance, in 1906, “Failure is impossible.”

> QUICK REVIEW

How did women’s temperance activism contribute to the cause of woman suffrage?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 567

Section Chronology