The Debate over American Imperialism

After a few brief campaigns in Cuba and Puerto Rico brought the Spanish-American War to an end, the American people woke up in possession of an empire that stretched halfway around the globe. As part of the spoils of war, the United States acquired Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. And Republicans quickly moved to annex Hawai’i in July 1898.

Contemptuous of the Cubans, whom General William Shafter declared “no more fit for self-government than gun-powder is for hell,” the U.S. government imposed a Cuban constitution and refused to give up military control of the island until the Cubans accepted the so-called Platt Amendment—a series of provisions that granted the United States the right to intervene to protect Cuba’s “independence,” as well as the power to oversee Cuban debt so that European creditors would not find an excuse for intervention. For good measure, the United States gave itself a ninety-nine-year lease on a naval base at Guantánamo. In return, McKinley promised to implement an extensive sanitation program to clean up the island, making it more attractive to American investors.

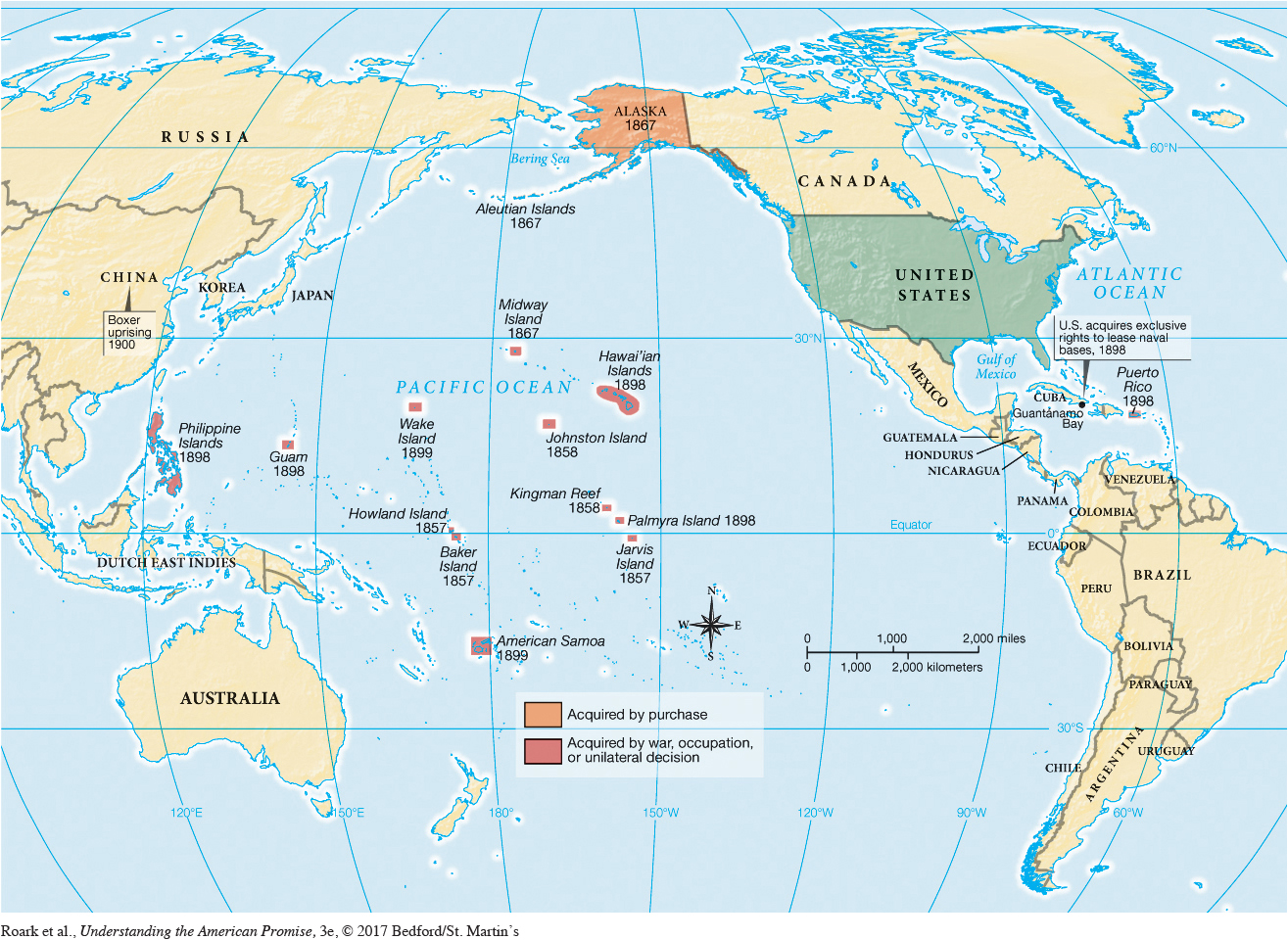

In the formal Treaty of Paris (1898), Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States along with the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico and Guam (Map 20.4). Empire did not come cheap. When Spain initially balked at these terms, the United States agreed to pay an indemnity of $20 million for the islands. Nor was the cost measured in money alone. Filipino revolutionaries under Emilio Aguinaldo, who had greeted U.S. troops as liberators, bitterly fought the new masters. It would take seven years and 4,000 American dead—almost ten times the number killed in Cuba—not to mention an estimated 20,000 Filipino casualties, to defeat Aguinaldo and secure American control of the Philippines. [[LP Map: M20.04 U.S. Overseas Expansion Through 1900 – MAP ACTIVITY/

At home, a vocal minority, mostly Democrats and former Populists, resisted the country’s foray into overseas empire, judging it unwise, immoral, and unconstitutional. William Jennings Bryan, who enlisted in the army but never saw action, concluded that American expansionism only distracted the nation from problems at home. Pointing to the central paradox of the war, Representative Bourke Cockran of New York admonished, “We who have been the destroyers of oppression are asked now to become its agents.” But the expansionists won the day. As Senator Knute Nelson of Minnesota assured his colleagues, “We come as ministering angels, not as despots.” Fresh from its conquest of Native Americans in the West, the nation largely embraced the heady mixture of racism and missionary zeal that fueled American adventurism abroad. The Washington Post trumpeted, “The taste of empire is in the mouth of the people,” thrilled at the prospect of “an imperial policy, the Republic renascent, taking her place with the armed nations.”

> QUICK REVIEW

How did Americans respond to U.S. overseas expansion?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 578

Section Chronology