The Homestead Lockout

In 1892, steelworkers in Pennsylvania squared off against Andrew Carnegie in a decisive struggle over the right to organize in the Homestead steel mills. Carnegie resolved to crush the Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers, one of the largest and richest craft unions in the American Federation of Labor (AFL). When the Amalgamated attempted to renew its contract at Carnegie’s Homestead mill, its leaders were told that since “the vast majority of our employees are Non union, the Firm has decided that the minority must give place to the majority.” While it was true that only 800 skilled workers belonged to the elite Amalgamated, the union had long enjoyed the support of the plant’s 3,000 non-union workers. Slavs, who did much of the unskilled work, made common cause with the Welsh, Scottish, and Irish skilled workers who belonged to the union.

Carnegie, who often praised labor unions, preferred not to be directly involved in the union busting, so that spring he sailed to Scotland and left Henry Clay Frick, the toughest antilabor man in the industry, in charge. By summer, a strike looked inevitable. Frick prepared by erecting a fifteen-foot fence around the Homestead plant and topping it with barbed wire. Workers aptly dubbed it “Fort Frick.” Frick then hired 316 mercenaries from the Pinkerton National Detective Agency at the rate of $5 per day, more than double the wage of the average Homestead worker.

On June 28, the Homestead lockout began when Frick locked the doors of the mills and prepared to bring in strikebreakers. Hugh O’Donnell, the young Irishman who led the union, vowed to prevent “scabs” from entering the plant. On July 6 at 4 a.m., a lookout spotted two barges moving up the Monongahela River in the fog. Frick was attempting to smuggle his Pinkertons into Homestead.

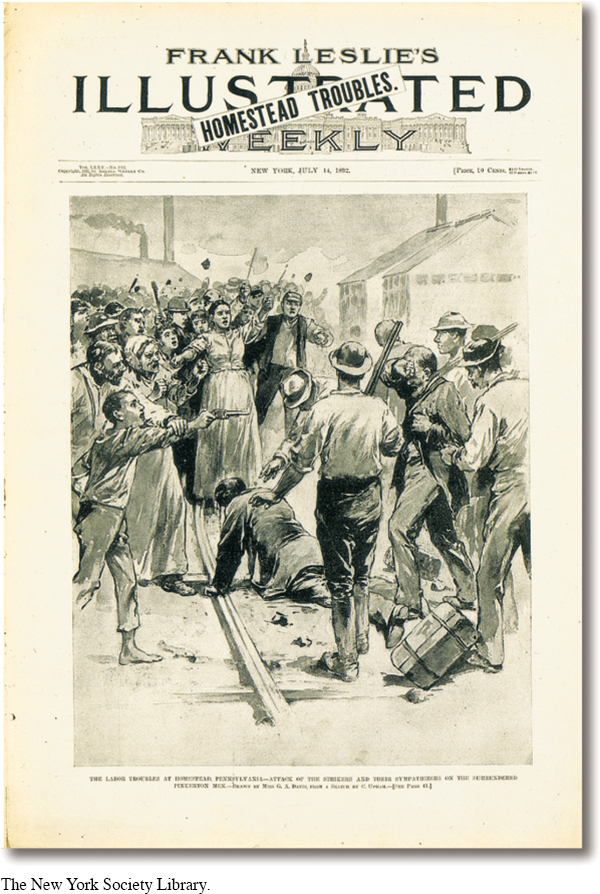

Workers sounded the alarm, and within minutes a crowd of more than a thousand, hastily armed with rifles, hoes, and fence posts, rushed to the riverbank. When the scabs attempted to come ashore, gunfire broke out, and more than a dozen Pinkertons and some thirty strikers fell, killed or wounded. The Pinkertons retreated to the barges. For twelve hours, the workers, joined by their family members, threw everything they had at the barges, from fireworks to dynamite. Finally, the Pinkertons hoisted a white flag and arranged with O’Donnell to surrender. With three workers dead and scores wounded, the crowd, numbering perhaps ten thousand, was in no mood for conciliation. As the hated “Pinks” came up the hill, they were forced to run a gantlet of screaming, cursing men, women, and children. When a young guard dropped to his knees, weeping for mercy, a woman used her umbrella to poke out his eye. One Pinkerton had been killed in the siege on the barges. In the grim rout that followed their surrender, not one avoided injury. The workers took control of the plant and elected a council to run the community. At first, public opinion favored their cause. A congressman castigated Carnegie for “skulking in his castle in Scotland.” Populists, meeting in St. Louis, condemned the use of “hireling armies.” [[LP Photo: P20.03 Homestead Workers Attack the Pinkertons/

The action of the Homestead workers struck at the heart of the capitalist system, pitting the workers’ right to their jobs against the rights of private property. The workers’ insistence that “we are not destroying the property of the company—merely protecting our rights” did not prove as compelling to the courts and the state as the property rights of the owners. Four days after the confrontation, Pennsylvania’s governor, who sympathized with the workers, nonetheless yielded to pressure from Frick and ordered eight thousand National Guard troops into Homestead to protect Carnegie’s property. The workers, thinking they had nothing to fear from the militia, welcomed the troops with a brass band. But the troops’ occupation not only protected Carnegie’s property but also enabled Frick to reopen the mills and bring in strikebreakers. “We have been deceived,” one worker complained bitterly. “We have stood idly by and let the town be occupied by soldiers who come here, not as our protectors, but as the protectors of non-union men. . . . If we undertake to resist the seizure of our jobs, we will be shot down like dogs.”

Then, in a misguided effort to ignite a general uprising, Alexander Berkman, a Russian immigrant and anarchist, attempted to assassinate Frick. Berkman bungled his attempt. Shot twice and stabbed with a dagger, Frick survived and showed considerable courage, allowing a doctor to remove the bullets but refusing to leave his desk until the day’s work was completed. “I do not think that I shall die,” Frick remarked coolly, “but whether I do or not, the Company will pursue the same policy and it will win.”

After the assassination attempt, public opinion turned against the workers. Berkman was quickly tried and sentenced to prison. Although the Amalgamated and the AFL denounced his action, the incident linked anarchism and unionism. O’Donnell later wrote, “The bullet from Berkman’s pistol, failing in its foul intent, went straight through the heart of the Homestead strike.” The Homestead mill reopened in November, and the men returned to work, except for the union leaders, now blacklisted in every steel mill in the country. With the owners firmly in charge, the company slashed wages, reinstated the twelve-hour day, and eliminated five hundred jobs.

The workers at Homestead had been taught a lesson. They would never again, in the words of the National Guard commander, “believe the works are theirs quite as much as Carnegie’s.” Another forty-five years would pass before steelworkers, unskilled as well as skilled, successfully unionized. In the meantime, Carnegie’s production tripled, even in the midst of a depression. “Ashamed to tell you profits these days,” Carnegie wrote a friend in 1899. And no wonder: Carnegie’s profits had grown from $4 million in 1892 to $40 million in 1900.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 559

Section Chronology