ANALYZING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE: The Flash and the Birth of Photojournalism

ANALYZING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

The Flash and the Birth of Photojournalism

Photography changed the way Americans viewed their world. By the 1890s, any amateur could purchase the Kodak camera that George Eastman marketed with the slogan “You push the button, we do the rest.” As the poet Oliver Wendell Holmes observed, the camera became not just “the mirror of reality” but “the mirror with a memory.”

Yet for Jacob Riis, a progressive reformer wishing to document the grim horrors of tenement life, photography was useless because it required daylight or careful studio lighting. He could only crudely sketch the dim hovels, the criminal nightlife, and the windowless tenement rooms of New York. Then came the breakthrough: “One morning scanning my newspaper at my breakfast table, I put it down with an outcry. . . . There it was, the thing I had been looking for all these years. . . . A way had been discovered to take pictures by flashlight.”

Riis set out to shine light in the dark corners of New York. “Our party carried terror wherever it went,” Riis recalled. “The spectacle of strange men invading a house in the midnight hours armed with [flash] pistols which they shot off recklessly was hardly reassuring.” But the results were a huge step forward for photojournalism.

Riis’s book How the Other Half Lives (1890) made photographic history. Along with Riis’s text and engravings of his drawings, it contained reproductions of seventeen photographs taken with his camera and flash. By looking at a line drawing side by side with the corresponding photograph, we can compare the impact of the two mediums.

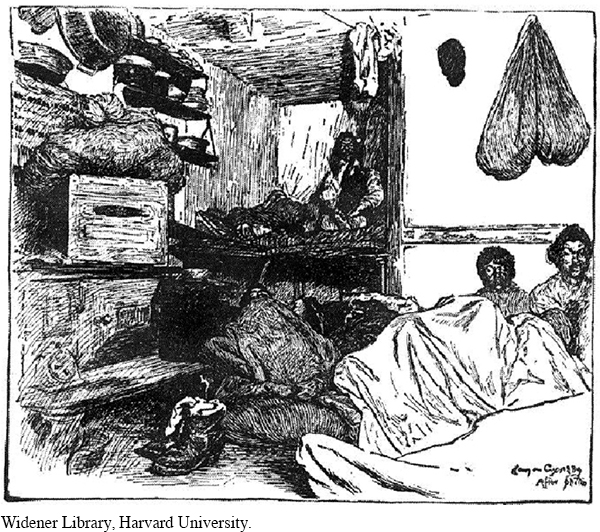

DOCUMENT 1

In his early work, Riis had to rely on his own sketches of the conditions he encountered in New York’s tenements. Riis is a careful draughtsman, but how much detail can you see in the line drawing above? [[LP Photo: P21.05 Five Cents a Spot (Drawing) - Analyzing Historical Evidence/

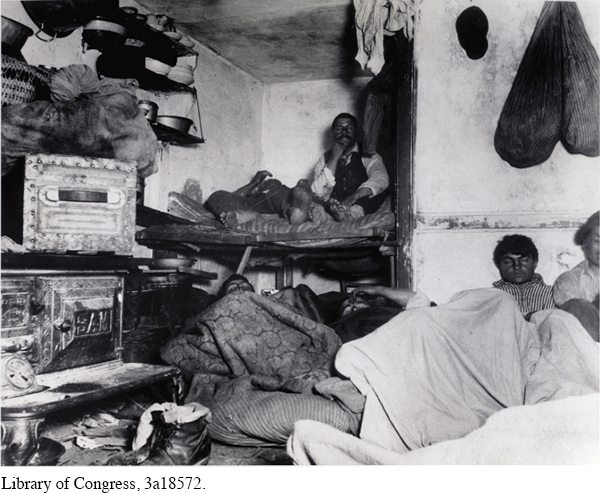

DOCUMENT 2

On a police raid to evict tenement lodgers, Riis describes the room as “not thirteen feet either way,” in which “slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor.” Note how the flash catches the sleepy faces and tired bodies, the crowding, dirt, and disorder above. Once Riis adopted the flash, he was able to show more graphically life in the tenements. What details are visible in the photograph that are missing in the line drawing? [[LP Photo: P21.06 Five Cents a Spot (Photo) - Analyzing Historical Evidence/

DOCUMENT 3

Riis took his camera into Baxter Street Court and recorded these observations: “I counted the other day the little ones up to ten years old in a . . . tenement that for a yard has a . . . space in the center with sides fourteen or fifteen feet long, just enough for a row of ill-smelling closets [toilets] . . . and a hydrant. There was about as much light in the ‘yard’ as in the average cellar. . . . I counted one hundred twenty eight [children] in forty families.” Riis’s pioneering photojournalism shocked the nation and led not only to tenement reform but also to the development of city playgrounds, neighborhood parks, and child labor laws.

Questions for Analysis

SUMMARIZE THE ARGUMENT: How significant is the advent of flash photography? Compare the drawn image with the photograph. Why is the photo so much more dramatic?

ANALYZE THE EVIDENCE: Would you agree that Riis’s photographs are “a mirror of reality,” or did he interpret and frame the “reality” he photographed?

ASK HISTORICAL QUESTIONS: How do you think photography affected Americans’ views of their society?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 595

Section Chronology