The War in France

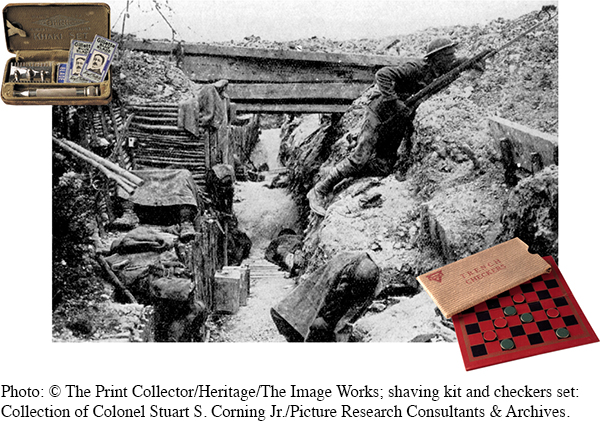

At the front, the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) discovered a desperate situation. The war had degenerated into a stalemate of armies dug into hundreds of miles of trenches that stretched across France. Huddling in the mud among the corpses and rats, soldiers were separated from the enemy by only a few hundred yards of “no-man’s-land.” When ordered “over the top,” troops raced desperately toward the enemy’s trenches, only to be entangled in barbed wire, enveloped in poison gas, and mowed down by machine guns. The three-day battle of the Somme in 1916 cost the French and British forces 600,000 dead and wounded and the Germans 500,000. The deadliest battle of the war allowed the Allies to advance their trenches only a few meaningless miles.

Still, U.S. troops saw almost no combat in 1917. Troops continued to train and used much of their free time to explore places that most of them could otherwise never hope to see. True to the crusader image, American officials allowed only uplifting tourism. The temptations of Paris were off-limits. French premier Georges Clemenceau’s offer to supply American troops with licensed prostitutes was declined with the half-serious remark that if Wilson found out he would stop the war. [[LP Photo: P22.03 Life in the Trenches (photo)/

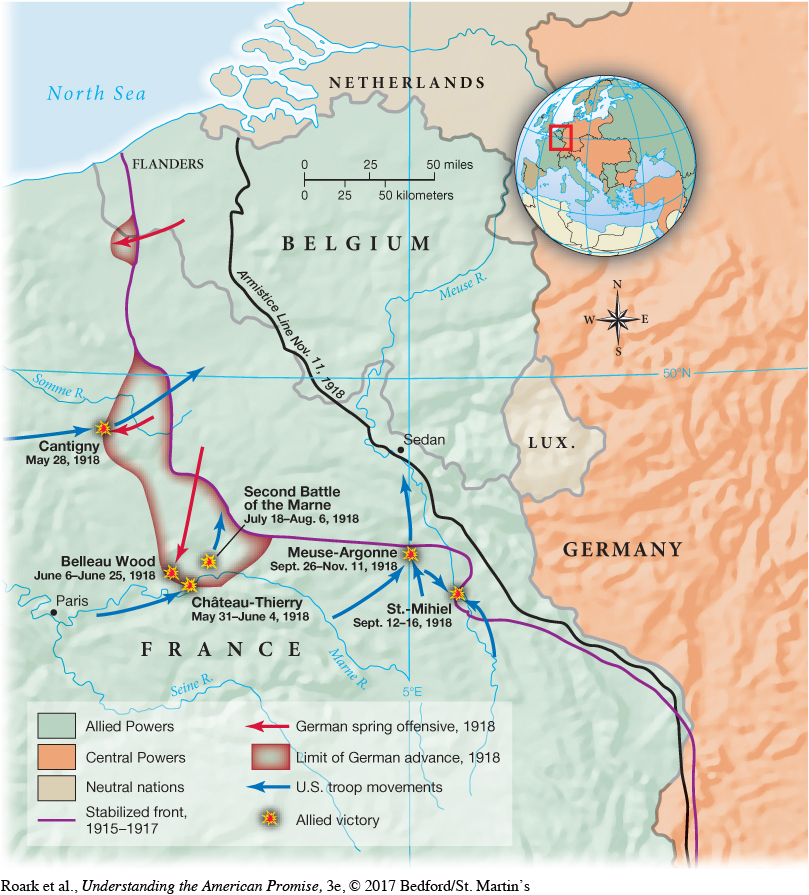

Sightseeing ended abruptly in March 1918 when a million German soldiers punched a hole in the Allied lines. Pershing finally committed the AEF to combat. In May and June, at Cantigny and then at Château-Thierry, the eager but green Americans checked the German advance with a series of assaults (Map 22.3). Then they headed toward the forest stronghold of Belleau Wood, moving against streams of retreating Allied soldiers who cried defeat: “La guerre est finie!” (The war is over!) A French officer commanded the Americans to retreat with them, but the American commander replied sharply, “Retreat, hell. We just got here.” After charging through a wheat field against withering machine-gun fire, the Marines plunged into hand-to-hand combat. Victory came hard, but a German report praised the enemy’s spirit, noting that “the Americans’ nerves are not yet worn out.” Indeed, it was German morale that was on the verge of cracking. [[LP Map: M22.03 The American Expeditionary Force, 1918 – MAP ACTIVITY/

In the summer of 1918, the Allies launched a massive counteroffensive that would end the war. A quarter of a million U.S. troops joined in the rout of German forces along the Marne River. In September, more than a million Americans took part in the assault that threw the Germans back from positions along the Meuse River. In four brutal days, the AEF sustained 45,000 casualties. In November, a revolt against the German government sent Kaiser Wilhelm II fleeing to Holland. On November 11, 1918, a delegation from the newly established German republic met with the French high command to sign an armistice that brought the fighting to an end.

> COMPARE AND CONTRAST

How did the experiences of AEF soldiers in World War I differ from those of Europeans, and what, if anything, did they have in common?

The adventure of the AEF was brief, bloody, and victorious. When Germany had resumed unrestricted U-boat warfare in 1917, it had been gambling that it could defeat Britain and France before the Americans could raise and train an army and ship it to France. The German military had miscalculated badly. By the end, 112,000 AEF soldiers perished from wounds and disease, while another 230,000 Americans suffered casualties but survived. Only the Civil War, which lasted much longer, had cost more American lives. European nations, however, suffered much greater losses: 2.2 million Germans, 1.9 million Russians, 1.4 million French, and 900,000 Britons. Where they had fought, the landscape was as blasted and barren as the moon.

> QUICK REVIEW

How did the AEF contribute to the defeat of Germany?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 623

Section Chronology