Postwar Politics and the Election of 1920

A thousand miles away in Washington, D.C., President Woodrow Wilson, bedridden and paralyzed, ignored the mountain of domestic troubles—labor strikes, the Red scare, race riots, immigration backlash—and insisted that the 1920 election would be a “solemn referendum” on the League of Nations. Dutifully, the Democratic nominees for president, James M. Cox of Ohio, and for vice president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt of New York, campaigned on Wilson’s international ideals. The Republican Party chose the handsome, gregarious Warren Gamaliel Harding, senator from Ohio.

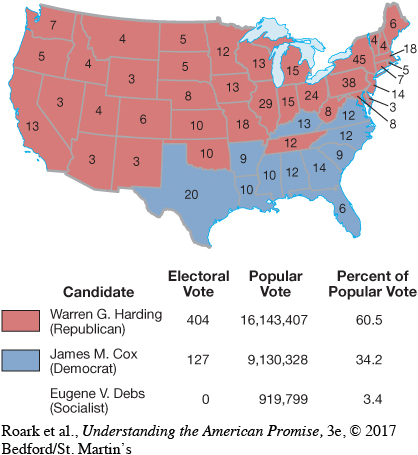

Harding found the winning formula when he declared that “America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums [questionable remedies] but normalcy.” But what was “normalcy”? Harding explained: “By ‘normalcy’ I don’t mean the old order but a regular steady order of things. I mean normal procedure, the natural way, without excess.” Eager to put wartime crusades and postwar strife behind them, voters responded by giving Harding the largest presidential victory ever: 60.5 percent of the popular vote and 404 out of 531 electoral votes (Map 22.6). Harding’s election lifted the national pall, signaling a new, more easygoing era. [[LP Map: M22.06 The Election of 1920/

> QUICK REVIEW

How did the Red scare contribute to the erosion of civil liberties after the war?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 642

Section Chronology