Automobiles, Mass Production, and Assembly-Line Progress

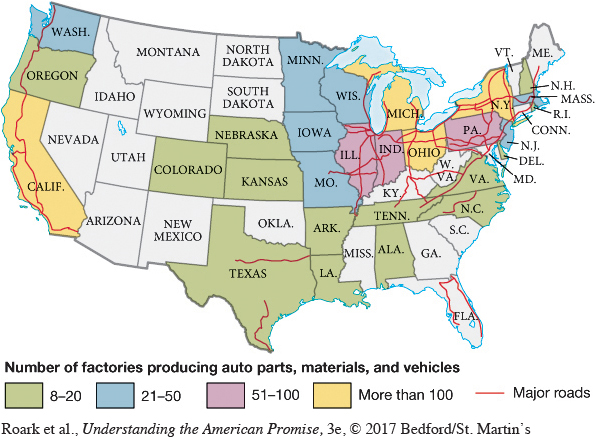

The automobile industry emerged as the largest single manufacturing industry in the nation. Henry Ford shrewdly located his company in Detroit, knowing that key materials for his automobiles were manufactured in nearby states (Map 23.1). Keystone of the American economy, the automobile industry not only employed hundreds of thousands of workers directly but also brought whole industries into being—filling stations, garages, fast-food restaurants, and “guest cottages” (motels). The need for tires, glass, steel, highways, oil, and refined gasoline for automobiles provided millions of related jobs. By 1929, one American in four found employment directly or indirectly in the automobile industry. “Give us our daily bread” was no longer addressed to the Almighty, one commentator quipped, but to Detroit.[[LP Map: M23.01 Auto Manufacturing – MAP ACTIVITY/

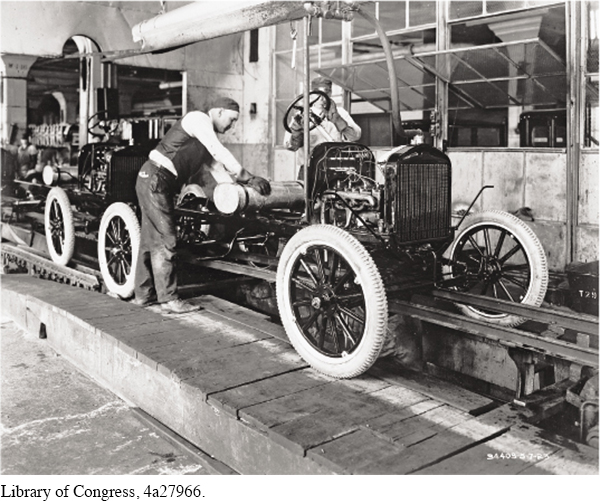

Automobiles changed where people lived, what work they did, how they spent their leisure, even how they thought. Hundreds of small towns decayed because the automobile enabled rural people to bypass them in favor of more distant cities and towns. In cities, streetcars began to disappear as workers moved to the suburbs and commuted to work along crowded highways. Nothing shaped modern America more than the automobile, and efficient mass production made the automobile revolution possible.[[LP Photo: P23.03 Auto assembly line/

Mass production by the assembly-line technique became standard in almost every factory, from automobiles to meatpacking to cigarettes. To improve efficiency, corporations reduced assembly-line work to the simplest, most repetitive tasks. Changes on the assembly line and in management, along with technological advances, significantly boosted overall efficiency. Between 1922 and 1929, productivity in manufacturing increased 32 percent. Average wages, however, increased only 8 percent.

> UNDERSTAND

POINTS OF VIEW

What motivated American industrial leaders in the 1920s to develop welfare capitalism programs? What did business owners think they had to gain by creating such programs, and what did they fear they might lose if they did not do so?

Industries also developed programs for workers that came to be called welfare capitalism. Some businesses improved safety and sanitation inside factories. They also instituted paid vacations and pension plans. Welfare capitalism encouraged loyalty to the company and discouraged traditional labor unions. One labor organizer in the steel industry bemoaned the success of welfare capitalism. “So many workmen here had been lulled to sleep by the company union, the welfare plans, the social organizations fostered by the employer,” he declared, “that they had come to look upon the employer as their protector, and had believed vigorous trade union organization unnecessary for their welfare.”

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 651

Section Chronology