Consumer Culture

Mass production fueled corporate profits and national economic prosperity. During the 1920s, per capita income increased by a third, the cost of living stayed the same, and unemployment remained low. But the rewards of the economic boom were not evenly distributed. Americans who labored with their hands inched ahead, while white-collar workers enjoyed significantly more money and more leisure time to spend it. Mass production of a broad range of new products—automobiles, radios, refrigerators, electric irons, washing machines—produced a consumer goods revolution.

In this new era of abundance, more people than ever conceived of the American dream in terms of the things they could acquire. Middletown (1929), a study of the inhabitants of Muncie, Indiana, revealed that Muncie had become, above all, “a culture in which everything hinges on money.” Moreover, faced with technological and organizational change beyond their comprehension, many citizens had lost confidence in their ability to play an effective role in civic affairs. More and more they became passive consumers, deferring to the supposed expertise of leaders in politics and economics.

The rapidly expanding business of advertising stimulated the desire for new products and attacked the traditional values of thrift and saving. Advertising linked material goods to the fulfillment of every spiritual and emotional need. Americans increasingly defined and measured their social status, and indeed their personal worth, on the yardstick of material possessions. Happiness itself rode on owning a car and choosing the right cigarettes and toothpaste. (See “Analyzing Historical Evidence: Advertising in a Consumer Age.”)

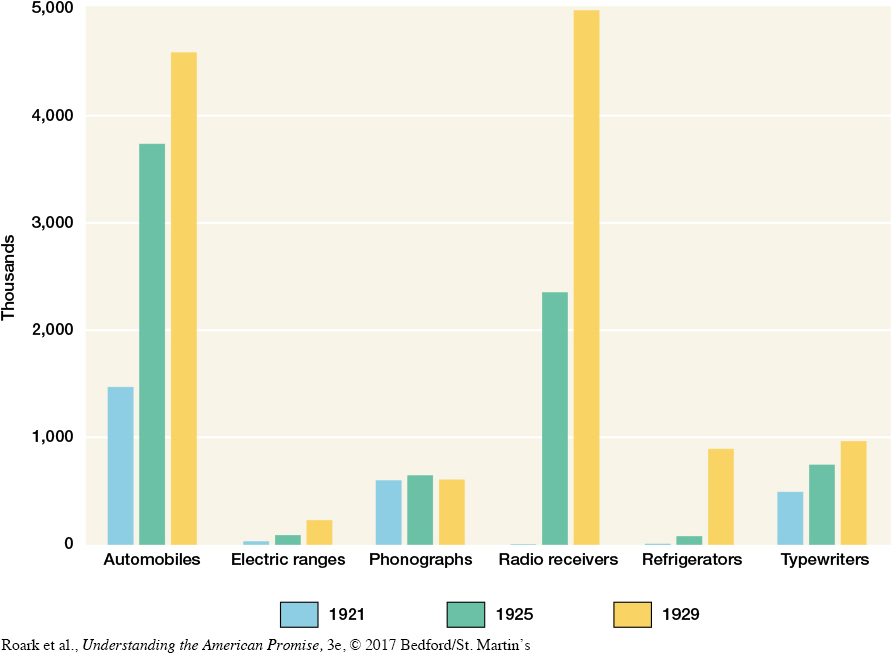

By the 1920s, the United States had achieved the physical capacity to satisfy Americans’ material wants (Figure 23.1). The economic problem shifted from production to consumption: Who would buy the goods flying off American assembly lines? One solution was to expand America’s markets in foreign countries, and government and business joined in that effort. Another solution to the problem of consumption was to expand the market at home. [[LP Figure: F23.01 Production of Consumer Goods, 1921–1929/

Henry Ford realized early on that “mass production requires mass consumption.” He understood that automobile workers not only produced cars but would also buy them if they made enough money. “One’s own employees ought to be one’s own best customers,” Ford said. In 1914, he raised wages in his factories to $5 a day, more than twice the going rate. High wages made for workers who were more loyal and more exploitable, and high wages returned as profits when workers bought Fords.

Many people’s incomes, however, were too puny to satisfy the growing desire for consumer goods. The solution was installment buying—a little money down, a payment each month—which allowed people to purchase expensive items they could not otherwise afford or to purchase items before saving the necessary money. As one newspaper announced, “The first responsibility of an American to his country is no longer that of a citizen, but of a consumer.” During the 1920s, America’s motto became spend, not save. Old values—“Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without”—seemed about as pertinent as a horse and buggy. American culture had shifted.

> QUICK REVIEW

How did the spread of the automobile transform the United States?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 652

Section Chronology