ANALYZING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE: Advertising in a Consumer Age

ANALYZING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

Advertising in a Consumer Age

Just as American business changed dramatically in the early decades of the twentieth century, so, too, did advertising. Businesses in the New Era sought to attract customers in new and different ways. Before the 1920s, advertising had focused on production. Even small businesses presented themselves as powerful and efficient producers of consumer goods such as stoves and furniture. But beginning in the consumer society of the 1920s, companies sought to teach Americans to judge themselves and others not by what they produced but by what they bought.

DOCUMENT 1

The Art of Making People Uneasy

In their study of Muncie, Indiana, sociologists Robert and Helen Merrell Lynd found that “advertising is to a business what fertilizer is to a farm” and examined the ways that large-scale advertising—in popular magazines, movies, radio, and elsewhere—was rapidly changing ideas about “what things are essential to living.”

[A]dvertising is concentrating increasingly upon a type of copy aiming to make the reader emotionally uneasy, to bludgeon him with the fact that decent people don’t live the way he does; decent people ride on balloon tires, have a second bathroom, and so on. The copy points an accusing finger at the stenographer as she reads her Motion Picture Magazine and makes her acutely conscious of her unpolished finger nails, or a worn place in the living room rug, and sends the housewife peering anxiously in the mirror to see if her wrinkles look like those that made Mrs. X—in the ad “old at thirty-five” because she did not have a Leisure Hour electric washer.

Source: Robert S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, Middletown: A Study in Contemporary American Culture (New York: 1928), 47, 82.

DOCUMENT 2

Unmasking Advertising

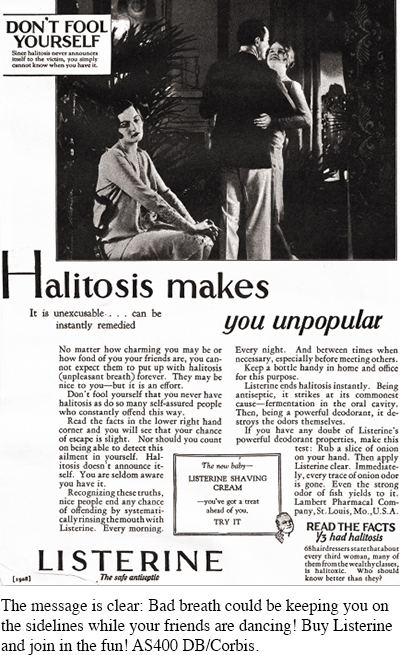

Frederick Lewis Allen, a journalist and historian, was an acute observer of contemporary life. In his enormously popular Only Yesterday, published only two years after the 1920s ended, he contemplates an advertising campaign based on anxiety about bad breath.

By far the most famous of these dramatic advertisements of the Post-war Decade was the long series in which the awful results of halitosis were set forth through the depiction of a gallery of unfortunates whose closest friends would not tell them. “Often a bridesmaid but never a bride. . . . Edna’s case was really a pathetic one.” . . . “Why did she leave him that way?” . . . “That’s why you’re a failure,” . . . and then that devilishly ingenious display which capitalized on the fears aroused by earlier tragedies in the series: the picture of a girl looking at a Listerine advertisement and saying to herself, “This can’t apply to me!” Useless for the American Medical Association to insist that Listerine was “not a true deodorant,” that it simply covered one smell with another. Just as useless as for the Life Extension Institute to find “one out of twenty with pyorrhea [gum disease], rather than Mr. Forhan’s [a mouth product] famous four-out-of-five.” . . . Halitosis had the power of dramatic advertising behind it, and Listerine swept to greater and greater profits on a tide of public trepidation.

Source: Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (New York: 1931), 144–45.

DOCUMENT 3

“Messenger to the King”

Not every observer of the avalanche of new advertising found it objectionable. William Chenery, editor and publisher of Collier’s, a national magazine, sang advertising’s praises in this 1930 article in his magazine.

Advertising, essentially, is the awakening of human desire. There is no stronger force in this new world of ours.

The successful advertisement makes you crave new things. The motive is frankly commercial but the consequences reach far beyond trade. . . . [T]he byproducts of the [advertiser’s] efforts have had prodigious effects upon our opinions, our standards of taste, our habits, and even upon our picture of a good life.

We arise in the morning and we bathe. Why? Merely because soap makers have taught us the importance of cleanliness. . . .

Beards and even mustaches have gone out of fashion because razor manufacturers persuaded us to shave.

We clean our teeth because toothpaste manufacturers have made us believe in the importance of oral hygiene. They have saved us from more aches than the dentists could cure.

Our breakfast habits are the results of the teaching of food manufacturers. The old heavy American breakfast has gone the way of the hoop skirt. Our health is better. Advertising did it.

The clothes we wear, the houses we live in, the furniture we use, our very conception of a home is the product of advertising. . . .

If journalism is the little sister of literature, advertising began certainly as the Cinderella of selling. Now it is the great motive force in our commercial life. It is the life blood of public demand. Our material civilization has been made possible by it.

Source: William Chenery, “Messenger to the King,” Collier’s, May 3, 1930.[[LP Photo P23.04 Ad for breath freshener – AHE Illustration/

Questions for Analysis

ANALYZE THE EVIDENCE: According to the critics—Frederick Lewis Allen and the Lynds—what is the most pernicious feature of modern advertising?

RECOGNIZE VIEWPOINTS: How might William Chenery’s job have helped shape his positive opinion of advertising? How might the other writers included here dispute his argument?

CONSIDER THE CONTEXT: How did the rise of mass production translate into the rise of mass advertising and mass consumption?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 654

Section Chronology