Building a Citizen Army

In 1940, Roosevelt encouraged Congress to pass the Selective Service Act to register men of military age who would be subject to a draft if the need arose. More than 6,000 local draft boards registered more than 30 million men and, when the war came, rapidly inducted them into military service. In all, more than 16 million men and women served in uniform during the war, two-thirds of them draftees, mostly young men. Women were barred from combat duty, but they worked at nearly every noncombatant task, eroding traditional barriers to women’s military service.

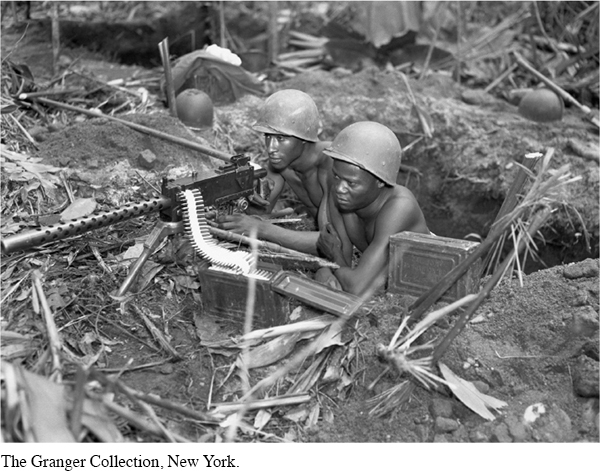

The Selective Service Act prohibited discrimination “on account of race or color,” and almost a million African American men and women donned uniforms, as did half a million Mexican Americans, 25,000 Native Americans, and 13,000 Chinese Americans. The racial insults and discrimination suffered by all people of color made some soldiers ask, as a Mexican American GI did on his way to the European front, “Why fight for America when you have not been treated as an American?” Only black Americans were trained in segregated camps, confined in segregated barracks, and assigned to segregated units.

Most black Americans were consigned to manual labor, and relatively few served in combat until late in 1944, when the need for military manpower in Europe intensified. Then, as General George Patton told black soldiers in a tank unit in Normandy, “I don’t care what color you are, so long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sonsabitches.”[[LP Photo: P25.04 African American Machine Gunners/

> PLACE EVENTS

IN CONTEXT

How did the U.S. military’s mobilization for war both challenge and reflect contemporary attitudes about race, gender, and sexuality?

Homosexuals also served in the armed forces, although in much smaller numbers than black Americans. Allowed to serve as long as their sexual preferences remained covert, gay Americans, like other minorities, sought to demonstrate their worth under fire. “I was superpatriotic,” a gay combat veteran recalled. Another gay GI remarked, “Who in the hell is going to worry about [homosexuality]” in the midst of the life-or-death realities of war?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 718

Section Chronology