Modern Republicanism

In contrast to the old guard conservatives in his party who criticized containment and wanted to repeal much of the New Deal, Dwight D. Eisenhower preached “modern Republicanism.” This meant resisting additional federal intervention in economic and social life, but not turning the clock back to the 1920s. “Should any political party attempt to abolish social security and eliminate labor laws and farm programs,” he wrote privately in 1954, “you would not hear of that party again in our political history.” Democratic control of Congress after the elections of 1954 further contributed to Eisenhower’s moderate approach.

The new president attempted to distance himself from the anti-Communist fervor that had plagued the Truman administration, even as he intensified Truman’s loyalty program, allowing federal executives to dismiss thousands of employees on grounds of loyalty, security, or “suitability.” Reflecting his inclination to avoid controversial issues, Eisenhower refused to denounce Senator Joseph McCarthy publicly. But, in 1954, McCarthy began to destroy himself when he hurled reckless charges of communism against military personnel during televised hearings. When the army’s lawyer demanded of McCarthy, “Have you left no sense of decency?” those in the hearing room applauded. A Senate vote in 1954 to condemn him marked the end of his influence but not the end of harassing dissenters on the left.

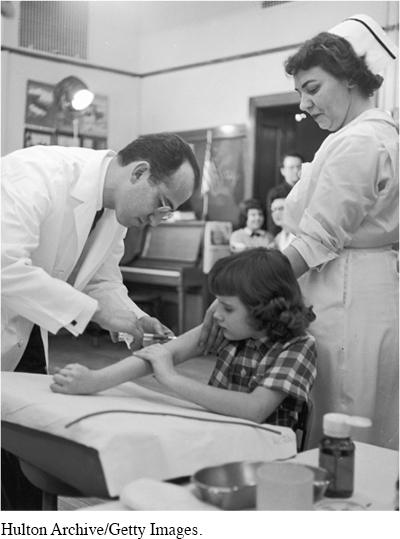

Eisenhower sometimes echoed conservative Republicans’ conviction that government was best left to the states and economic decisions to private business. Yet he signed laws bringing ten million more workers under Social Security, increasing the minimum wage, and creating a new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. And when the spread of polio neared epidemic proportions, Eisenhower obtained funds from Congress to distribute a vaccine, even though conservatives wanted the states to bear that responsibility. [[LP Photo: P27.02 The Polio Vaccine/

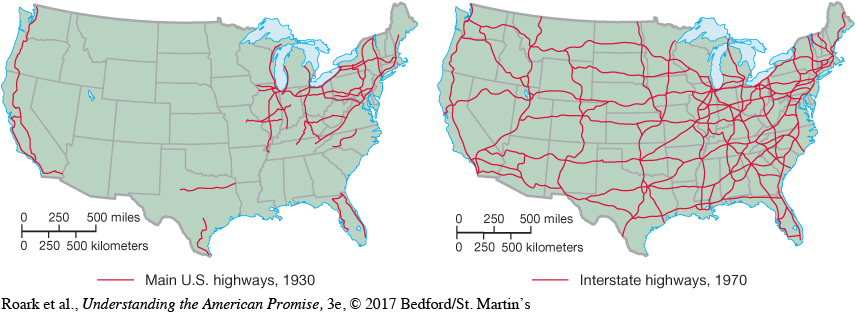

Eisenhower’s greatest domestic initiative was the Interstate Highway and Defense System Act of 1956 (Map 27.1). Promoted as essential to national defense and an impetus to economic growth, the act authorized construction of a national highway system, with the federal government paying most of the costs through increased fuel and vehicle taxes. The new highways accelerated the mobility of people and goods, spurred suburban expansion, and benefited the trucking, construction, and automobile industries that had lobbied hard for the law. Eventually, the monumental highway project exacted unforeseen costs in the form of air pollution, energy consumption, declining railroads and mass transportation, and decay of central cities.[[LP Map: M27.01 The Interstate Highway System, 1930 and 1970 – MAP ACTIVITY/

> PLACE EVENTS

IN CONTEXT

How did the implementation of Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway and Defense System Act of 1956 reflect the major domestic and international concerns of the 1950s?

In other areas, Eisenhower restrained federal activity in favor of state governments and private enterprise. His large tax cuts directed most benefits to business and the wealthy, and he resisted federal aid to primary and secondary education as well as strong White House leadership on behalf of civil rights. Eisenhower opposed national health insurance, preferring the growing practice of private insurance provided by employers. Although Democrats sought to keep nuclear power in government hands, Eisenhower signed legislation authorizing the private manufacture and sale of nuclear energy. The first commercial nuclear power plant opened in 1958 in northwest Pennsylvania.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 769

Section Chronology