Meeting the “Hour of Maximum Danger”

Underlying Kennedy’s foreign policy was an assumption that the United States had “gone soft—physically, mentally, spiritually soft,” as he put it in 1960. Calling the Eisenhower era “years of drift and impotency,” Kennedy warned in his inaugural address that the nation faced a grave peril: “Each day the crises multiply. . . . Each day we draw nearer the hour of maximum danger.”

Although the president exaggerated the threat to national security, several developments in 1961 heightened the sense of crisis and provided a rationalization for his military buildup. Shortly before Kennedy’s inauguration, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev publicly encouraged “wars of national liberation,” thereby aligning the Soviet Union with independence movements in the third world that were often anti-Western. His statement reflected in part the Soviet competition with China for the allegiance of emerging nations, but U.S. officials saw it as a threat to the status quo of containment.

Cuba, just ninety miles off the Florida coast, posed the first crisis for Kennedy. The revolution led by Fidel Castro had moved Cuba into the Soviet orbit, and Eisenhower’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had planned an invasion of the island by Cuban exiles living in Florida. Kennedy ordered the invasion to proceed even though his military advisers deemed its success uncertain.

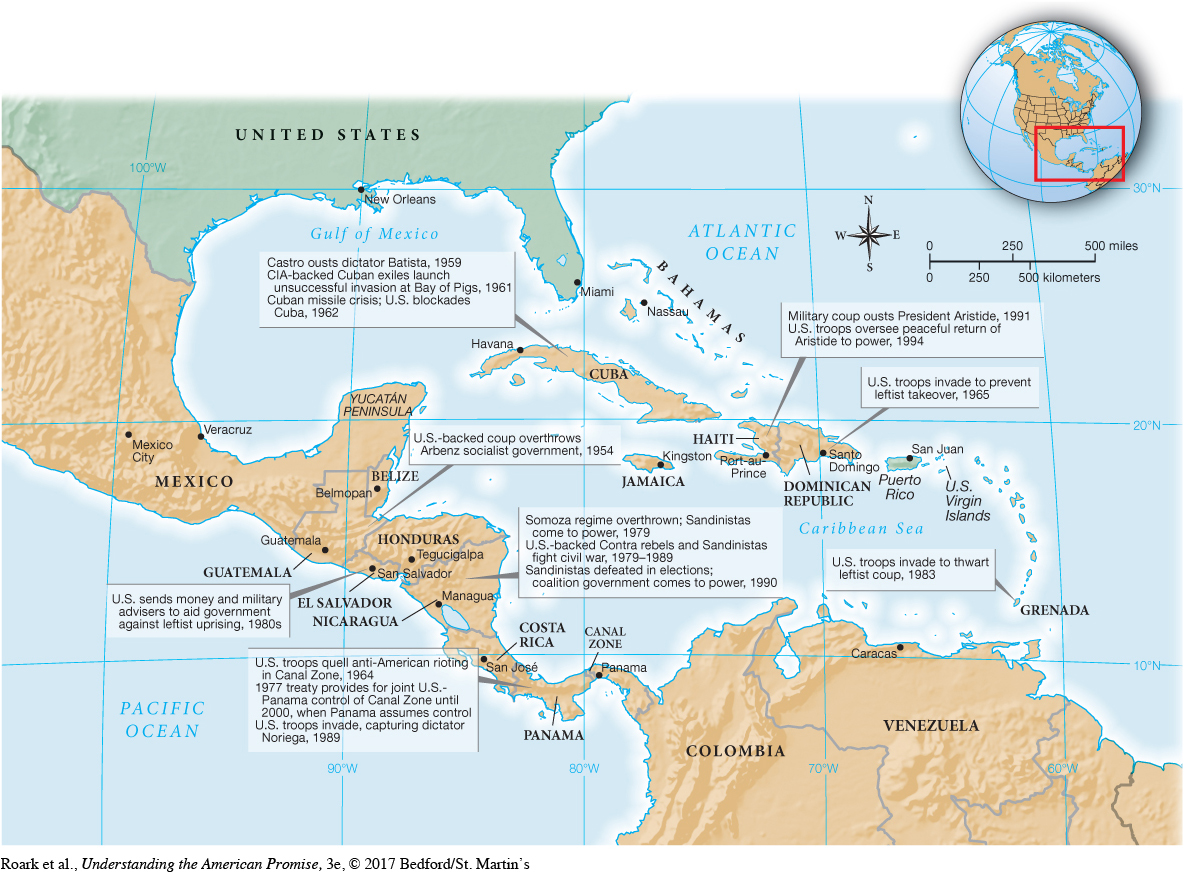

In April 1961, about 1,400 anti-Castro exiles trained and armed by the CIA landed at the Bay of Pigs on the south shore of Cuba (Map 29.1). Contrary to U.S. expectations, no popular uprising materialized to support the anti-Castro brigade. Kennedy refused to provide direct military support, and the invaders quickly fell to Castro’s forces. The disaster humiliated Kennedy and the United States, posing a stark contrast to the president’s inaugural promise of a new, more effective foreign policy. And it alienated Latin Americans who saw it as another example of Yankee imperialism. [[LP Map: M29.01 U.S. Involvement in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1954–1994 – MAP ACTIVITY/

Days before the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Soviet Union dealt a psychological blow when a Soviet astronaut became the first human to orbit the earth. Kennedy then called for a huge new commitment to the space program, with the goal of sending a man to the moon by 1970. Congress authorized the Apollo program and boosted appropriations for space exploration. John H. Glenn orbited the earth in 1962, and the United States beat the Soviets to the moon, landing two astronauts there in 1969.

Kennedy was determined to show American toughness to Khrushchev, but when the two met in June 1961 in Vienna, Austria, Khrushchev took the offensive. The stunned Kennedy reported privately, “He just beat [the] hell out of me. . . . If he thinks I’m inexperienced and have no guts . . . we won’t get anywhere with him.” Khrushchev demanded an agreement recognizing the existence of two Germanys, and he threatened U.S. occupation rights in and access to West Berlin.

The Soviet premier was concerned about the massive exodus of East Germans into West Berlin, a major embarrassment for the Communists. To stop this flow, in August 1961 East Germany erected a wall between the sectors. With the Berlin Wall stemming the tide of escapees and Kennedy declaring West Berlin “the great testing place of Western courage and will,” Khrushchev backed off from his threats. A decade later the superpowers recognized East and West Germany as separate nations and guaranteed Western access to West Berlin.

Kennedy used the Berlin crisis to add $3.2 billion to the defense budget. He increased draft calls and mobilized the reserves and National Guard, adding 300,000 troops to the military. This buildup of conventional forces provided for a “flexible response,” offering “a wider choice than humiliation or all-out nuclear action,” yet Kennedy also more than doubled the nation’s nuclear force within three years.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 829

Section Chronology