The Arms Race and the Nuclear Brink

The final piece of Kennedy’s foreign policy was to strengthen American nuclear dominance. He tripled the number of nuclear weapons based in Europe to 7,200 and multiplied fivefold the supply of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Concerned that this buildup would enable the United States to launch a first strike and wipe out Soviet missile sites before they could respond, the Soviet Union stepped up its own ICBM program. Thus began the most intense arms race in history.

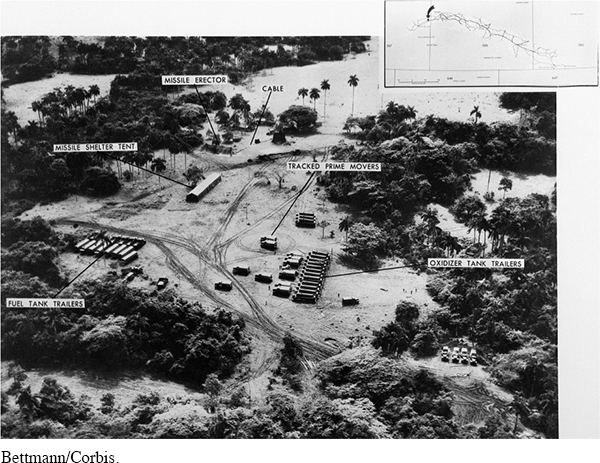

The superpowers came perilously close to using their weapons during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. Khrushchev decided to install nuclear missiles in Cuba to protect Castro’s regime from further U.S. attempts at invasion and to balance the U.S. missiles aimed at the Soviet Union from Europe. On October 22, after the CIA showed Kennedy aerial photographs of missile launching sites under construction in Cuba, Kennedy announced that the military was on full alert and that the navy would turn back any Soviet vessel suspected of carrying missiles to Cuba. He warned that any attack launched from Cuba would trigger a full nuclear assault against the Soviet Union. [[LP Spot Map: SM29.01 Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962/

With the superpowers on the brink of nuclear war, both Kennedy and Khrushchev also exercised caution. Kennedy refused advice from the military to bomb the missile sites. On October 24, Russian ships carrying nuclear warheads toward Cuba suddenly turned back. When one ship crossed the blockade line, Kennedy ordered the navy to follow it rather than confront it. [[LP Photo: P29.02 Cuban Missile Crisis/

While Americans experienced the Cold War’s most dangerous days, Kennedy and Khrushchev negotiated an agreement. The Soviets removed the missiles and pledged not to introduce new offensive weapons into Cuba. The United States promised not to invade the island. Secretly, Kennedy also agreed to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey. The Cuban crisis contributed to Khrushchev’s fall from power two years later, while Kennedy emerged triumphant. The image of an inexperienced president fumbling the Bay of Pigs invasion gave way to that of a strong leader.

> ANALYZE EVIDENCE

To what extent does the compromise agreement made by Khrushchev and Kennedy support Kennedy’s claim that the resolution of the Cuban missile crisis was a major American victory?

Having proved his toughness, Kennedy worked to ease superpower hostilities. In June 1963, Kennedy called for a reexamination of Cold War assumptions, asking Americans “not to see conflict as inevitable.” Acknowledging the superpowers’ differences, Kennedy stressed what they had in common: “We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future and we are all mortal.” In August 1963, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Great Britain signed a limited nuclear test ban treaty, reducing the threat of radioactive fallout and raising hopes for further superpower accord.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 831

Section Chronology