Emergence of a Grassroots Movement

Hidden beneath Lyndon B. Johnson’s landslide victory over Arizona senator Barry Goldwater in 1964 lay a rising conservative movement. Defining his purpose as “enlarging freedom at home and safeguarding it from the forces of tyranny abroad,” Goldwater argued that government intrusions into economic life hindered prosperity, stifled personal responsibility, and interfered with citizens’ rights to determine their own values. Conservatives assailed big government in domestic affairs but demanded a strong military to eradicate “Godless communism.”

The grassroots movement supporting Goldwater’s nomination was especially vigorous in the South and West, and it included middle-class suburban women and men, members of the rabidly anti-Communist John Birch Society, and college students in the new Young Americans for Freedom (YAF). In 1966, California conservatives helped Ronald Reagan defeat the liberal incumbent governor, whom Reagan linked to the Watts riot, student disruptions at California universities, and rising taxes.

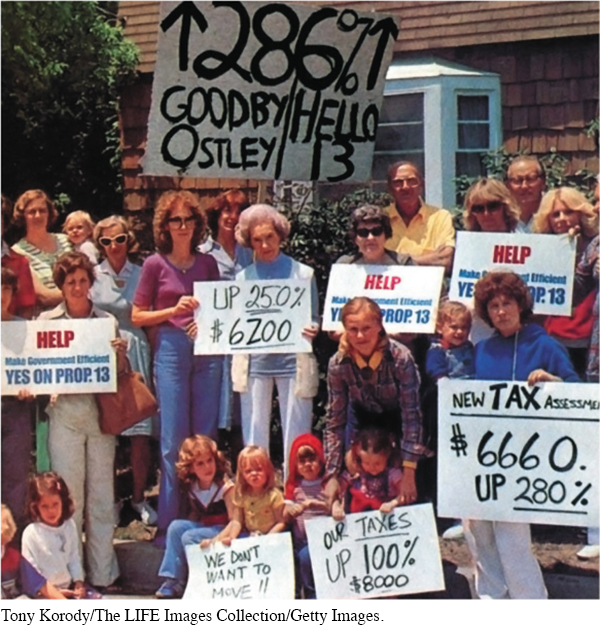

A number of Sun Belt characteristics made conservatism strong in places such as Orange County, California; Dallas, Texas; and Scottsdale, Arizona. These predominantly white areas contained relatively homogeneous, skilled, and economically comfortable populations, as well as military bases and defense plants. The West harbored a long-standing tradition of Protestant morality, individualism, and opposition to interference by a remote federal government, although that tradition was hardly consistent with the Sun Belt’s economic dependence on defense spending and on huge federal projects providing water and power for the burgeoning region. The South, which also benefited from military bases and the space program, shared the West’s antipathy toward the federal government, but hostility to racial change was much more central to the South’s conservatism. After signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, President Johnson remarked privately, “I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party.” [[LP Photo: P30.02 The Tax Revolt/

Grassroots movements proliferated around what conservatives believed marked the “moral decline” of their nation. For example, in 1962 Mel and Norma Gabler got the Texas Board of Education to drop books that they believed undermined “the Christian-Judeo morals, values, and standards as given to us by God through . . . the Bible.” Sex education roused the ire of Eleanor Howe in Anaheim, California, who felt that “nothing [in the sex education curriculum] depicted my values.” The U.S. Supreme Court’s liberal decisions on school prayer, obscenity, and abortion also galvanized conservatives to restore “traditional values.”

> COMPARE AND CONTRAST

How did the emerging New Right of the 1960s and 1970s mirror some of the perspectives that economic and cultural conservatives expressed in the 1920s? In what ways did they differ, and why?

In the 1970s, grassroots protests against taxes grew alongside concerns about morality. As Americans struggled with inflation and unemployment, many found themselves paying higher taxes, especially higher property taxes as the value of their homes increased. Some were incensed to see their taxes fund government programs for people they considered undeserving. In 1978, Californians revolted in a popular referendum, slashing property taxes and limiting the state legislature’s ability to raise other taxes. What a newspaper called a “primal scream by the People against Big Government” spread to other states.

Law and order was yet another rallying cry of the right, reflecting concerns about rising rates of crime, which were due in part to baby boomers maturing into the age group most prone to crime. Conservatives lumped common crime with civil disobedience and antiwar protest into a cry for law and order, and blamed liberals for Great Society programs that had failed to reduce crime, permissive attitudes toward protesters, and Supreme Court decisions that coddled criminals. A Pennsylvania man called “crime, the streets being unsafe, strikes, the trouble with the colored, all this dope-taking . . . a breakdown of the American way of life.”

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 857

Section Chronology