The Pilgrims and Plymouth Colony

One of the first Protestant groups to emigrate, later known as Pilgrims, professed an unorthodox view known as separatism. These Separatists sought to withdraw—or separate—from the Church of England, which they considered hopelessly corrupt. In 1608 they moved to Holland; by 1620 they realized that they could not live and worship there as they had hoped. William Bradford, a leader of the Separatists, recalled that “many of their children, by . . . the great licentiousness of youth [in Holland], and the manifold temptations of the place, were drawn away by evil examples.” Bradford and other Separatists believed that America promised to better protect and preserve their children and their community. Separatists obtained permission to settle in the extensive territory granted to the Virginia Company (see “The Fragile Jamestown Settlement” in chapter 3). In August 1620, Pilgrim families boarded the Mayflower, and after eleven weeks at sea all but one of the 102 immigrants arrived at the outermost tip of Cape Cod in present-day Massachusetts.

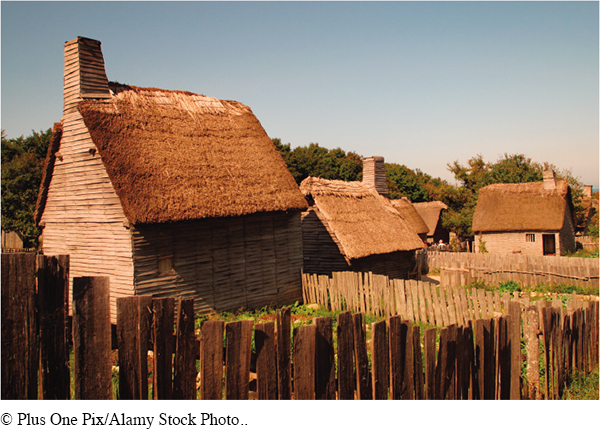

The Pilgrims realized immediately that they had landed far north of the Virginia grants and had no legal authority to settle in the area. To provide order, security, and a claim to legitimacy, they drew up the Mayflower Compact on the day they arrived. They pledged to “covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation.” The signers (all men) agreed to enact and obey necessary and just laws. [[LP Photo: P04.03 Plymouth Village/

The Pilgrims settled at Plymouth and elected William Bradford their governor. That first winter, which they spent aboard their ship, “was most sad and lamentable,” Bradford wrote later. “In two or three months’ time half of [our] company died . . . being the depth of winter, and wanting houses . . . [and] being infected with scurvy and other diseases.”

In the spring, Indians rescued the floundering Plymouth settlement. First Samoset and then Squanto befriended the settlers. Samoset had learned English from previous contacts with sailors and fishermen who had visited the coast to dry fish before the Plymouth settlers arrived. Squanto had been kidnapped by an English trader in 1614 and taken as a slave to Spain, where he escaped to London and learned English before finally making his way back home. Samoset arranged for the Pilgrims to meet and establish good relations with Massasoit, the chief of the Wampanoag Indians, whose territory included Plymouth. Squanto, Bradford wrote, “was a special instrument sent of God for their [the Pilgrims’] good. . . . He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities.” With the Indians’ guidance, the Pilgrims managed to harvest enough food to guarantee their survival through the coming winter, an occasion they celebrated in the fall of 1621 with a feast of thanksgiving attended by Massasoit and other Wampanoags.

Plymouth colony remained precarious for years, but the Pilgrims persisted, living simply and coexisting in relative peace with the Indians. One settler contrasted the group’s improved circumstances with their former homes in England by noting, “We are all free-holders [here], the [landlords’] rent-day doth not trouble us.” By 1630, Plymouth had become a small permanent settlement, but it failed to attract many other English Puritans.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 80

Section Chronology