Pontiac’s Rebellion and the Proclamation of 1763

One glaring omission marred the Treaty of Paris: The major powers at the treaty table failed to include or consult the Indians. Minavavana, an Ojibwa chief of the Great Lakes region, put it succinctly to an English trader: “Englishman, although you have conquered the French, you have not yet conquered us! We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods and mountains were left to us by our ancestors . . . ; and we will part with them to none.” Furthermore, Minavavana pointedly noted, “your king has never sent us any presents, nor entered into any treaty with us, wherefore he and we are still at war.”

Minavavana’s complaint about the absence of British presents was significant. To Indians, gifts cemented social relationships, symbolizing honor and establishing obligation. Over many decades, the French had mastered the subtleties of gift exchange, distributing textiles and hats and receiving calumets (ceremonial pipes) in return. British military leaders, new to the practice, often discarded the calumets as trivial trinkets, thereby insulting the givers. From the British view, a generous gift might signify tribute (thus demeaning the giver), or it might be positioned as a bribe. “It is not my intention ever to attempt to gain the friendship of Indians by presents,” Major General Jeffery Amherst declared. The Indian view was the opposite: Generous givers expressed dominance and protection, not subordination, in the ceremonial practices of giving.

Despite Minavavana’s confident words, Indians north of the Ohio River had cause for concern. Old French trading posts all over the Northwest were beefed up by the British into military bases. Fort Duquesne, renamed Fort Pitt to honor the victorious leader, gained new walls sixty feet thick at their base, announcing that this was no fur trading post. Tensions between the British and the Indians in this area ran high.

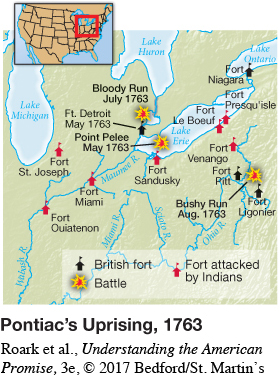

A religious revival among the Indians magnified feelings of antagonism toward the British. In 1763, the renewal of commitment to Indian ways and the formation of tribal alliances led to open warfare, which the British called Pontiac’s Rebellion, named for the chief of the Ottawas. In mid-May, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Huron warriors attacked Fort Detroit. Six more attacks on forts followed within weeks, and frontier settlements were raided by tribes from western New York, the Ohio Valley, and the Great Lakes region. By fall, Indians had captured every fort west of Detroit. More than four hundred British soldiers were dead and another two thousand colonists killed or taken captive. [[LP Spot Map: SM06.02 Pontiac’s Uprising, 1763/

Some Americans exacted revenge. The worst violent aggression occurred in late 1763, when some fifty Pennsylvania vigilantes known as the Paxton Boys descended on a peaceful village of friendly Conestoga Indians, murdering twenty. The vigilantes, now numbering five hundred, marched on Philadelphia to try to capture and murder some Christian Indians held in protective custody there. British troops prevented that, but the Paxton Boys escaped punishment for their murderous attack on the Conestoga village.

In early 1764, the uprising faded. The Indians were short on ammunition, and the British were tired and broke. The British government recalled the imperious general Amherst, blaming him for mishandling the conflict, and his own soldiers toasted his departure. A new military leader, Thomas Gage, took command and began distributing gifts profusely among the Indians.

To minimize violence, the British government issued the Proclamation of 1763, forbidding colonists to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains in order to protect Indian territory. But the Proclamation’s language also took care not to identify western lands as belonging to the Indians. Instead, it spoke of lands that “are reserved to [Indians], as their Hunting Grounds.”[[LP Photo: P06.03 Silver Medal to Present to Indians (King George II)/

> CONSIDER CAUSE

AND EFFECT

How did Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War transform its North American empire and relationship to Native Americans?

Other parts of the Proclamation of 1763 referred to American and even French colonists in Canada as “our loving subjects,” entitled to English rights and privileges. In contrast, the Indians were rejected as British subjects and described more vaguely as “Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected.” Of course, the British were not really well connected with any Indians, nor did they wish connections to form among the tribes. As William Johnson, the superintendent of northern Indian affairs, advised in 1764, “It will be expedient to treat with each nation separately . . . for could they arrive at a perfect union, they must prove very dangerous Neighbours.”

The 1763 boundary was a further provocation to American settlers and also to land speculators who (like the men of the Ohio Company) had already staked claims to huge tracts of western lands in hopes of profitable resale. Yet the boundary proved impossible to enforce. Surging population growth had already sent many hundreds of settlers, many of them squatters, west of the Appalachians. Periodic bloodshed continued and left the settlers fearful, uncertain about their futures, and increasingly wary of British claims to be a protective mother country.

> QUICK REVIEW

How did the Seven Years’ War erode relations between colonists and British authorities?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 142

Section Chronology