Burgoyne’s Army and the Battle of Saratoga

In 1777, British general John Burgoyne, commanding a considerable army, began the northern squeeze on the Hudson River valley. Coming from Canada, he marched south hoping to capture Albany, near the intersection of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers (see Map 7.1). Accompanied by 1,000 “camp followers” (cooks, laundresses, musicians) and some 400 Indian warriors, mostly Mohawks, Burgoyne’s army of 7,800 men did not travel light. Food had to be packed in, not only for people but for 400 horses hauling heavy artillery.

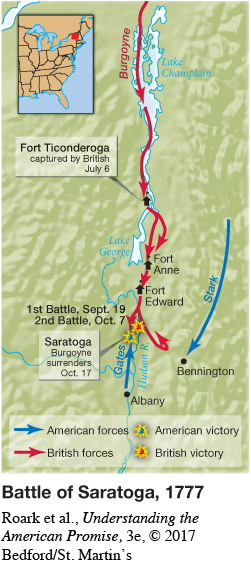

In July, Burgoyne captured Fort Ticonderoga with ease. American troops stationed there spotted the approaching British and abandoned the fort without a fight. The British continued to move south, but they lost a month hacking their way through dense forests. Supply lines back to Canada were severely stretched, and soldiers sent out to forage for food were beaten back by local militia units.

The logical second step in isolating New England should have been to advance troops up the Hudson from New York City to meet Burgoyne. American surveillance indicated that General Howe in Manhattan was readying his men for a major move in August 1777. But Howe surprised everyone by sailing south to attack Philadelphia.

To reinforce Burgoyne, British and Hessian troops from Montreal came from the west along the Mohawk River, aided by some thousand Mohawks and Senecas of the Iroquois Confederacy. A hundred miles west of Albany, the British encountered American Continental soldiers at Fort Stanwix and laid siege, causing hundreds of local patriot German militiamen and a number of Oneida Indians to rush to the Continentals’ support. On August 6, 1777, Mohawk chief Joseph Brant led his large force of warriors in an ambush on the patriot fighters in a narrow ravine called Oriskany. The result was one of the bloodiest battles of the entire war. Of the 800 local militiamen, nearly 400 were killed and another 50 were wounded in the carnage, while on Brant’s side, some 90 warriors died. The defenders of Fort Stanwix ultimately repelled their attackers, who retreated north to Canada. The deadly battle of Oriskany and battle of Fort Stanwix were complexly multiethnic, pitting German Americans against Hessian mercenaries, New York patriots against New York loyalists, English Americans against British soldiers, and Indians against Indians. They marked the beginning of the end of the Iroquois Confederacy, ruptured by lethal violence between members of the constituent tribes. By January 1779, the eternal flame of the council fire at Onondaga, which had symbolized the unity of the six confederated tribes of Iroquoia, was extinguished. [[LP Photo: UTAP3 07.06 Joseph Brandt /

The British retreat at Fort Stanwix deprived General Burgoyne of the additional troops he expected. Camped at a small village called Saratoga, he was isolated, with food supplies dwindling and men deserting. His adversary at Albany, General Horatio Gates, began moving his army toward Saratoga. Burgoyne decided to attack first, and the British prevailed, but at the great cost of 600 dead or wounded. Three weeks later, an American attack on Burgoyne’s forces in the second stage of the battle of Saratoga cost the British another 600 men and most of their cannons. General Burgoyne finally surrendered to the American forces on October 17, 1777. It was the first decisive victory for the American Continentals, touching off great celebration throughout the colonies. [[LP Spot Map: SM07.02 Battle of Saratoga, 1777/

General Howe, meanwhile, had succeeded in occupying Philadelphia in September 1777. Figuring that the Saratoga loss was balanced by the capture of Philadelphia, the British government proposed a negotiated settlement—not including independence—to end the war. The American side refused.

Patriot optimism was not well founded. Spirits ran high, but supplies of arms and food ran precariously low. Washington moved his troops into winter quarters at Valley Forge, just west of Philadelphia. Quartered in drafty huts, the men lacked blankets, boots, stockings, and food. Some 2,000 men at Valley Forge died of disease; another 2,000 deserted over the bitter six-month encampment.

Washington blamed the citizenry for lack of support; indeed, evidence of corruption and profiteering was abundant. Army suppliers too often provided defective food, clothing, and gunpowder. One shipment of bedding arrived with blankets one-quarter their customary size. Food supplies arrived rotten. As one Continental officer said, “The people at home are destroying the Army by their conduct much faster than Howe and all his army can possibly do by fighting us.”

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 184

Section Chronology