Pursuing Both War and Peace

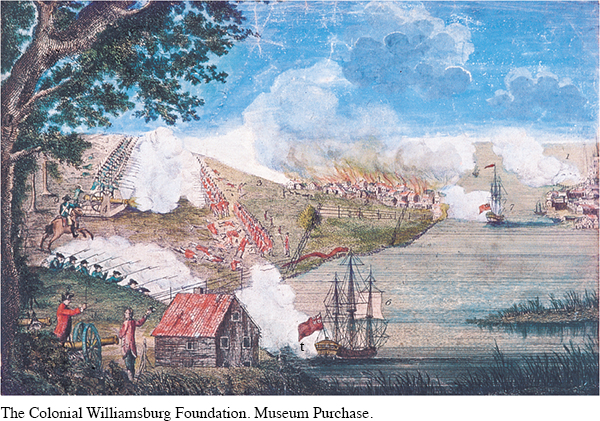

The second battle of the Revolution occurred on June 17 in Boston. New England militia units had fortified the hilly terrain of the peninsula of Charlestown, which faced the city, and Thomas Gage, still commander in Boston, prepared to attack, aided by the arrival of new troops and three talented generals, William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton. [[LP Photo: P07.02 An Exact View of the Late Battle at Charlestown, June 17th 1775 –/

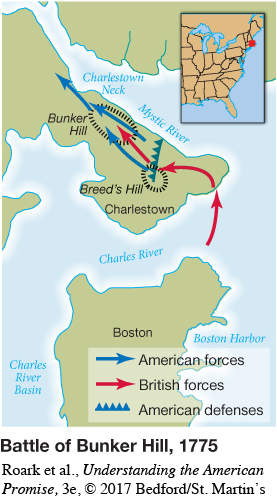

General William Howe insisted on a bold frontal assault, sending 2,500 soldiers across the water and up Bunker Hill in an intimidating but potentially costly attack. Three bloody assaults were needed before the British took the hill, the third succeeding mainly because the American ammunition supply gave out, and the defenders quickly retreated. The battle of Bunker Hill was thus a British victory, but an expensive one. The dead numbered 226 on the British side, with more than 800 wounded; the Americans suffered 140 dead, 271 wounded, and 30 captured. As General Clinton later remarked, “It was a dear bought victory; another such would have ruined us.” [[LP Spot Map: SM07.01 Battle of Bunker Hill, 1775/

Instead of pursuing the fleeing Americans, Howe retreated to Boston, unwilling to risk more raids into the countryside. If the British had had any grasp of the basic instability of the American units around Boston, they might have decisively defeated the Continental army in its infancy. Instead, they lingered in Boston, abandoning it without a fight nine months later.

Howe used the time in Boston to inoculate his army against smallpox because a new epidemic of the deadly disease was spreading in port cities along the Atlantic. Inoculation worked by producing a mild but real (and therefore risky) case of smallpox, followed by lifelong immunity. Howe’s instinct was right: During the American Revolution, some 130,000 people on the American continent, most of them Indians, died of smallpox.

A week after Bunker Hill, when General Washington arrived to take charge of the new Continental army, he found enthusiastic but undisciplined troops. Sanitation was an unknown concept, with inadequate latrines fouling the campground. Washington attributed the disarray to the New England custom of letting militia units elect their own officers, which he felt undermined deference. Washington spotted a militia captain, a barber in civilian life, shaving an ordinary soldier, and he moved quickly to impose more hierarchy and authority. “Be easy,” he advised his newly appointed officers, “but not too familiar, lest you subject yourself to a want of that respect, which is necessary to support a proper command.”

While military plans moved forward, the Second Continental Congress pursued its contradictory objective: reconciliation with Britain. Delegates from the middle colonies (Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New York), whose merchants depended on trade with Britain, urged that channels for negotiation remain open. In July 1775, congressional moderates led by John Dickinson engineered an appeal to the king called the Olive Branch Petition, affirming loyalty to the monarchy and blaming all the troubles on the king’s ministers and on Parliament. It proposed that the American colonial assemblies be recognized as individual parliaments under the umbrella of the monarchy. King George III rejected the Olive Branch Petition and heatedly condemned the Americans as traitors.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 170

Section Chronology