2d Considering your purpose and stance as a communicator

Contents:

Considering purposes for academic writing

Considering your rhetorical stance

In ancient Rome, the great orator Cicero noted that a good speech generally fulfills one of three major purposes: to delight, to teach, or to move. Today, our purposes when we communicate with one another remain pretty much the same: we seek to entertain (delight), to inform or explain (teach), and to persuade or convince (move).

Whether you choose to communicate for purposes of your own or have that purpose set for you by an instructor or employer, you should consider the purpose for any communication carefully. For the writing you do that is not connected to a class or work assignment, your purpose may be very clear to you: you may want to convince neighbors to support a community garden, get others in your office to help keep the kitchen clean, or tell blog readers what you like or hate about your new phone. Even so, analyzing what you want to accomplish and why can make you a more effective communicator.

Considering purposes for academic writing

Considering purposes for academic writing

Academic work requires particular attention to your reasons for writing. On one level, you are writing to establish your credibility with your instructor, to demonstrate that you are a careful thinker and an effective communicator. On another level, though, you are writing to achieve goals of your own, to say as clearly and forcefully as possible what you think about a topic.

For most college writing, consider purpose in terms of the assignment, the instructor’s expectations, and your own goals.

- What is the primary purpose of the assignment—

to entertain? to explain? to persuade? some other purpose? What does this purpose suggest about the best ways to achieve it? If you are unclear about the primary purpose, talk with your instructor. Are there any secondary purposes to keep in mind? - What are the instructor’s purposes in giving this assignment—

to make sure you have read certain materials? to determine your understanding? to evaluate your thinking and writing? How can you fulfill these expectations? - What are your goals in carrying out this assignment—

to meet expectations? to learn? to communicate your ideas? How can you achieve these goals?

Considering your rhetorical stance

Considering your rhetorical stance

Thinking about your own position as a communicator and your attitude toward your text—

A student writing a proposal for increased services for people with disabilities, for instance, knew that having a brother with Down syndrome gave her an intense interest that her audience might not have in this topic. She needed to work hard, then, to get her audience to understand—

- What is your overall attitude toward the topic? How strong are your opinions?

- What social, political, religious, personal, or other influences have contributed to your attitude?

- How much do you know about the topic? What questions do you have about it?

- What interests you most about the topic? Why?

- What interests you least about it? Why?

- What seems important—

or unimportant— about the topic? - What preconceptions, if any, do you have about it?

- What do you expect to conclude about the topic?

- How will you establish your credibility (ethos)? That is, how will you show that you are knowledgeable and trustworthy? (See 8d and 9e.)

Purpose and stance of visuals and media

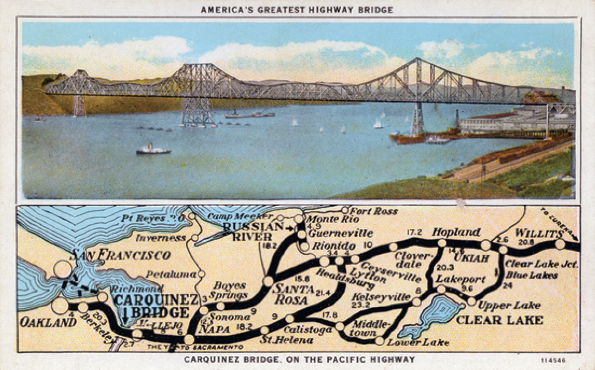

Images and media you choose to include in your writing can help establish credibility. But remember that they, too, always have a point of view or perspective. This postcard, for example, illustrates two physical perspectives—

Emily Lesk’s purposes

As she considered the assignment, Emily Lesk saw that her primary purpose was to explain the significance and implications of her topic to herself and her readers, but she recognized some other purposes as well. Because this essay was assigned early in the term, she wanted to get off to a good start; thus, one of her purposes was to write as well as she could to demonstrate her ability to her classmates and instructor. In addition, she decided that she wanted to find out something new about herself and to use this knowledge to get her readers to think about themselves.

For the first draft of Emily Lesk’s essay, see 3g. For the final draft of her essay, see 4l.