4b Reviewing peer writers' work

Contents:

Understanding the role of the peer reviewer

Working with peer reviewers in an online course

Using tools for peer review

Conducting a peer review

Basing responses on the stage of the draft

Quick Help: Guidelines for peer review

Storyboard on being a peer reviewer

Video Prompt: Lessons from being a peer reviewer

Whether you are part of a small peer-

Understanding the role of the peer reviewer

Understanding the role of the peer reviewer

The most helpful reviewers are interested in the topic and the writer’s approach to it. They ask questions, make concrete suggestions, report on what is confusing and why, and offer encouragement. Good reviewers give writers a new way to see their drafts so that they can revise effectively. After reading an effective review, writers should feel confident about taking the next step in the writing process.

Peer review is difficult for two reasons. First, offering writers a way to imagine their next draft is just hard work. Unfortunately, there’s no formula for giving good writing advice. But you can always do your best to offer your partner a careful, thoughtful response to the draft and a reasonable sketch of what the next version might contain. Second, peer review is challenging because your job as a peer reviewer is not to grade the draft or respond to it as an instructor would. As a peer reviewer, you will have a chance to think alongside writers whose writing you may consider much better or far worse than your own. Don’t dwell on these comparisons. Instead, remember that a thesis is well supported by purposefully arranged details, not by punctuation or impressive vocabulary. Your goal is to read the writer’s draft closely enough to hear what he or she is trying to say and to suggest a few strategies for saying it better.

Being a peer reviewer should improve your own writing as you see how other writers approach the same assignment. So make it a point to tell writers what you learned from their drafts; as you express what you learned, you’ll be more likely to remember their strategies. Also, you will likely begin reading your own texts in a new way. Although all writers have blind spots when reading their own work, you will gain a better sense of where readers expect cues and elaboration.

Working with peer reviewers in an online course

Working with peer reviewers in an online course

If you are taking an online writing class or MOOC, you can still take advantage of peer reviews. In an online course, you may be assigned to a peer-

Using tools for peer review

Using tools for peer review

Remember that one of your main goals as a peer reviewer is to help the writer see his or her draft differently. You want to show the writer what does and doesn’t work about particular aspects of the draft. Visually marking a draft can help the writer know at a glance what revisions the reviewer suggests. (Remember that visual mark-

Marking up a print draft

If you are reviewing a hard copy of a draft, write compliments in the left margin and critiques, questions, and suggestions in the right margin. As long as you explain what your symbols mean, you can also use circles, underlining, highlighting, or other visual annotations to point out patterns to the writer. If an idea is mentioned in several paragraphs, for example, you can circle those sentences and suggest that the writer use them to form a new paragraph.

Marking up a digital draft

If the draft comes to you as a digital file, save the document in a folder under a name you will recognize. It’s wise to include the writer’s name, the assignment, the number of the draft, and your initials. For example, Ann G. Smith might name the file for the first draft of Javier Jabari’s first essay jabari essay1 d1 ags.doc.

You can use the TRACK CHANGES function of your word-

For media drafts that are difficult to annotate visually, ask the writer about preferred ways to offer suggestions—

You should also consider using highlighting in written-

| Color | Revision Suggestion |

| Yellow | Read this sentence aloud, and then revise for clarity. |

| Green | This material seems out of place. Reorganize? |

| Blue | This idea isn’t clearly connected to your thesis. Cut? |

Conducting a peer review

Conducting a peer review

Whenever you respond to a piece of writing, think of the response you are giving—

Before you read the draft, ask the writer for any feedback instructions. Take the writer’s requests seriously. If, for example, the writer asks you to look at specific aspects of his or her writing and to ignore others, be sure to respond to that request.

To begin your review, read straight through the project and think about the writer’s specific instructions as well as these general guidelines.

A summary of the draft

After reading the draft, begin by summarizing the main idea(s) of the piece of writing. You might begin by writing I think the main argument is . . . or In this draft, you promise to. . . . Then outline the main points that support the thesis (3e and f).

Once you prepare the outline, your most important work as a peer reviewer can begin. You need to think alongside the writer about how to support the thesis and arrange details most effectively for the audience. Ask yourself the following questions and make notes that you can include in the letter to the writer:

- If I heard this topic mentioned in another situation, what would I expect the conversation to include? Would any of those ideas strengthen this writing?

- If I had not read this draft, what order would I expect these ideas to follow?

- Are any ideas or connections missing?

Your mark-

Next, as you reread the draft, use the mark-

Unlike in the personal letter, where you try to help the writer imagine the next draft, your comments, annotations, and other markings should respond to what is already written. Aim for a balance between compliments and constructive criticism. If you think the author has stated something well, comment on why you like it. If you have trouble understanding or following the writer’s ideas, comment on what you think may be causing problems. The chart here provides several examples of ways to frame effective marginal comments.

| Compliments | Constructive Criticism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A letter to the writer

Begin by addressing the writer by name (Dear Javier). Using your outline, identify the main points of the draft, and write your suggestions in the letter. You might use sentences like I didn’t understand ________. Could you explain it differently? I think ________ is your strongest point, and I recommend you move ________. This portion of the letter will help the writer make the most significant changes to the argument and supporting evidence.

After you have added all your mark-

- The strengths of the current draft. Refer to the outline you developed and your compliments.

- Two or three things you think will significantly improve the draft’s effectiveness. Refer to your constructive criticism.

- Areas on which the writer asked you to focus (if any).

Read over your comments once more, checking your tone and clarity. Close by signing your name. Save your response, and send it to the writer using the method recommended by your instructor.

Basing responses on the stage of the draft

Basing responses on the stage of the draft

You may be asked to review your peers’ work at any stage of the writing—

Early-

Writers of early-

Approach commenting on and marking up an early draft with three types of questions in mind:

- Fit. How does this draft fit the assignment? In what areas might the writer struggle to meet the criteria? How does this draft fit the audience? What else does the writer need to remember about the audience’s expectations and needs?

- Potential. What ideas in this draft are worth developing more? What other ideas or details could inform the argument? Are there other viewpoints on this topic that the writer should explore?

- Order. Considering only the parts that are worth keeping, what sequence do you recommend? What new sections do you think need to be added?

Intermediate-

Writers of intermediate-

Approach commenting on and marking up an intermediate draft with these types of questions in mind:

- Topic sentences and transitions. Topic sentences introduce the idea of a paragraph, and transitions move the writing smoothly from one paragraph or section or idea to the next (5b, e, and f). How well does the draft prepare readers for the next set of ideas by explaining how they relate to the overall claim? Look for ideas or details that don’t seem to fit into the overall structure of the draft. Is the idea or detail out of place because it is not well integrated into this paragraph? If so, recommend a revision or a new transition. Is it out of place because it doesn’t support the overall claim? If so, recommend deletion.

- Supporting details. Well-

developed paragraphs and arguments depend on supporting details (5c and d). Does the writer include an appropriate number and variety of details? Could the paragraph be improved by adding another example, a definition, a comparison or contrast, a cause- effect relationship, an analogy, a solution to a problem, or a personal narrative?

Late-

Writers of late-

Reviews of Emily Lesk’s draft

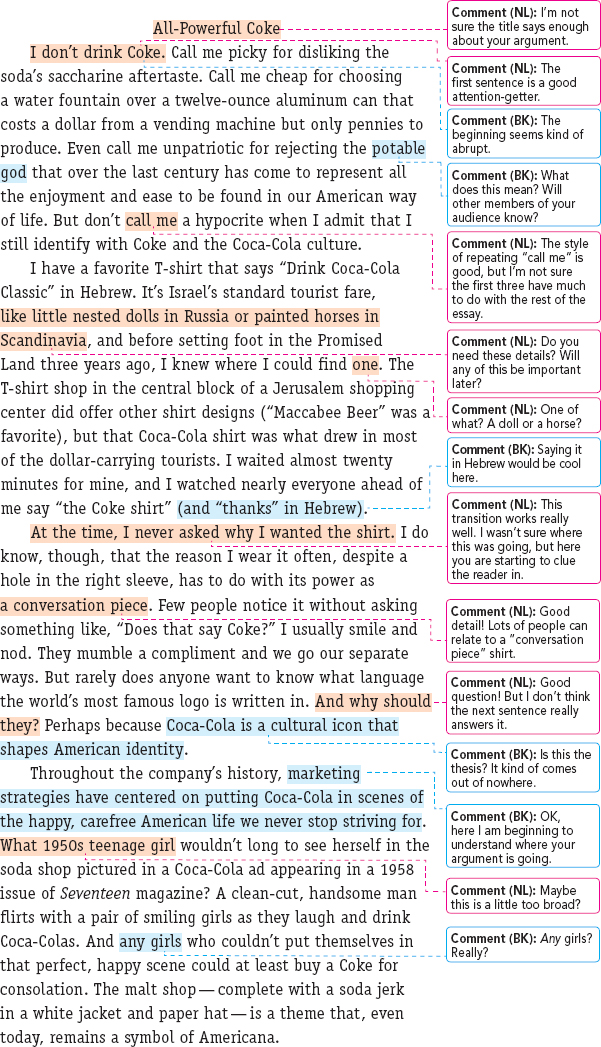

On the following pages are the first paragraphs of Emily Lesk’s draft, as reviewed by two students, Beatrice Kim and Nastassia Lopez. Beatrice and Nastassia reviewed the draft separately and combined their comments on the draft they returned to Emily. As this review shows, Nastassia and Bea agreed on some of the major problems—

The following is the text of an email message that Emily’s two peer-

Hi Emily:

We’re attaching your draft with our comments. Good luck on revising!

First, we think this is a great draft. You got us interested right away with the story about your T-

Your stance, though, is very clear, and we liked that you talked about how you were pulled into the whole Coke thing even though you don’t particularly like the soda. Sometimes we got bogged down in a ton of details, though, and felt like maybe you were telling us too much.

We were impressed with some of the words you use—

See you in class.

Nastassia and Bea

P.S. Could you add a picture of your T-

Emily also got advice from her instructor, who suggested that Emily do a careful outline of this draft to check for how one point led to another and to see if the draft stayed on track.

Based on her own review of her work as well as all of the responses she received, Emily decided to (1) make her thesis more explicit, (2) delete some extraneous information and examples, (3) integrate at least one visual into her text, and (4) work especially hard on the tone and length of her introduction and on word choice.

For Multilingual Writers: Understanding peer reviews

For Multilingual Writers: Reviewing a draft

For Multilingual Writers: Asking an experienced writer to review your draft