4i Revising paragraphs, sentences, words, and tone

Contents:

Revising paragraphs

Revising sentences

Revising words

Revising for tone

In addition to examining the larger issues of logic, organization, and development, effective writers look closely at the smaller elements: paragraphs, sentences, and words. Many writers, in fact, look forward to this part of revising and editing because its results are often dramatic. Turning a weak paragraph into a memorable one—

Revising paragraphs

Revising paragraphs

Paragraphing serves the reader by visually breaking up long expanses of writing and signaling a shift in focus. Readers expect a paragraph to develop an idea, a process that usually requires several sentences or more. These guidelines can help you revise your paragraphs:

- Look for the topic or main point of each paragraph, whether it is stated or implied. Does every sentence expand, support, or otherwise relate to the topic?

- Check to see how each paragraph is organized—

spatially, chronologically, associationally, or by some logical relationship (3e). Is this organization appropriate to the topic of the paragraph? - Note any paragraphs that have only a few sentences. Do these paragraphs sufficiently develop the topic of the paragraph?

For additional guidelines on editing paragraphs, see Quick Help: Editing the paragraphs in your writing.

Paragraph 5 in Emily Lesk’s draft (3g) contains only two sentences, and they don’t lead directly into the next paragraph. In her revision, Emily lengthened (and strengthened) the paragraph by adding a sentence that points out the result of Coca-

But while countless campaigns with this general strategy have together shaped the Coca-

Revising sentences

Revising sentences

As with life, variety is the spice of sentences. You can add variety to your sentences by looking closely at their length, opening patterns, and structure. (See the guidelines for editing sentences in Chapter 52.)

Sentence length

Too many short sentences, especially one after another, can sound like a series of blasts on a car horn, whereas a steady stream of long sentences may tire or confuse readers. Most writers aim for some variety of length.

Emily Lesk found that all the sentences in one paragraph were fairly long:

In other words, Coca-

In an early revision of her draft, Emily decided to shorten the second sentence, thereby inserting a short, easy-

In other words, Coca-

Sentence openings

Most sentences in English follow subject-

Emily Lesk’s second paragraph (see 3g) tells the story of how she got her Coke T-

Even before setting foot in Israel three years ago, I knew exactly where I could find the Coke T-

Sentences opening with it or there

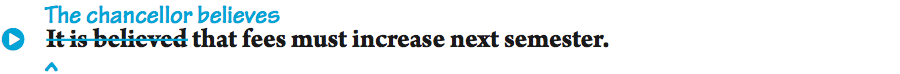

As you go over the sentences of your draft, look especially at those beginning with it is, it was, there is, there was, there are, or there were. Sometimes these words can create a special emphasis, as in “It was a dark and stormy night.” But they can also cause problems (50b). A reader doesn’t know what it means, for instance, unless the writer has already pointed out exactly what the word stands for. A more subtle problem with these openings, however, is that they may allow a writer to avoid taking responsibility for a statement:

The original sentence avoids responsibility by failing to tell us who believes that fees must increase.

Sentence structure

Using only simple sentences can be very dull, but overusing compound sentences may result in a singsong or repetitive rhythm. At the same time, strings of complex sentences may sound, well, overly complex. Try to vary your sentence structure (see Chapter 52).

Revising words

Revising words

Maybe even more than paragraphs and sentences, word choice—

- Do you use too many abstract and general nouns rather than concrete and specific ones? Saying that you bought a car is much less memorable than saying you bought a used Mini Cooper (30c).

- Are there too many nouns in relation to the number of verbs? The effect of the overuse of nouns in writing is the placing of too much strain on the inadequate number of verbs and the resultant prevention of movement of the thought. In the preceding sentence, the verb is carries the entire weight of all those nouns (in italics). The result is a heavy, boring sentence. Why not say instead, Overusing nouns places a big strain on the verbs and slows down the prose?

- How many verbs are forms of be—

be, am, is, are, was, were, being, been? If be verbs account for more than about a third of your total verbs, you are probably overusing them. (See 36a, 37c, Chapter 39, and 53b.) - Are most of your verbs active rather than passive? Although the passive voice has many uses (39g), your writing will generally be stronger and more energetic if you use active verbs.

- Are your words appropriate? Check to be sure they are not too fancy—

or too casual (30a).

Emily Lesk made a number of changes in word choice. She decided to change Promised Land to Israel since some of her readers might not regard these two as synonymous. She also made her diction more lively, changing from Fords to Tylenol to from Allstate insurance to Ziploc bags to take advantage of the A-

Revising for tone

Revising for tone

Word choice is closely related to tone, the attitude that a writer’s language carries toward the topic and the audience. In examining the tone of your draft, think about the nature of the topic, your own attitude toward it, and that of your intended audience. Check for connotations of words as well as for slang, jargon, emotional language, and your level of formality. Does your language create the tone you want to achieve (humorous, serious, impassioned, and so on)? Is that tone appropriate, given your audience and topic? (For more on creating an appropriate tone through word choice, see Chapter 30.)

Although Emily Lesk’s peer reviewers liked the overall tone of her essay, one reviewer had found her opening sentence abrupt. To make her tone friendlier, she decided to preface I don’t drink Coke with another clause, resulting in America, I have a confession to make: I don’t drink Coke. Emily also shortened her first paragraph considerably, in part to eliminate the know-