12g Taking notes and annotating sources

Contents:

Using quotations

Using paraphrases

Using summaries

Taking other kinds of notes

Annotating source material

Quick Help: Guidelines for quotation notes

Quick Help: Guidelines for paraphrase notes

Quick Help: Guidelines for summaries

Note-

The following example shows the major items a note should include:

Use a subject heading. Label or title each note with a brief, descriptive heading so that you can group similar subtopics together.

Use a subject heading. Label or title each note with a brief, descriptive heading so that you can group similar subtopics together.

Identify the source. List the author’s name and a shortened title of the source, and a page number, if available. Your working-

Identify the source. List the author’s name and a shortened title of the source, and a page number, if available. Your working-

Indicate whether the note is a direct quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Make sure quotations are copied accurately. Put square brackets around any change you make, and use ellipses if you omit material.

Indicate whether the note is a direct quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Make sure quotations are copied accurately. Put square brackets around any change you make, and use ellipses if you omit material.

Taking complete notes will help you digest the source information as you read and incorporate the material into your text without inadvertently plagiarizing the source (see Chapter 14). Be sure to reread each note carefully, and recheck it against the source to make sure quotations, statistics, and specific facts are accurate. (For more information on working with quotations, paraphrases, and summaries, see Chapter 13.)

Using quotations

Using quotations

Some of the notes you take will contain quotations, which give the exact words of a source.

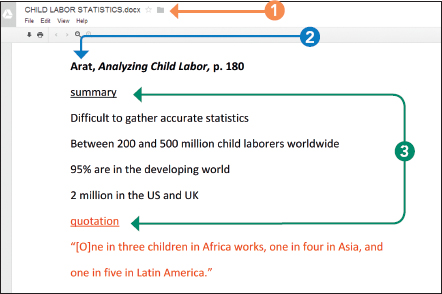

Here is a note with a quotation that student Benjy Mercer-

Name of document indicates subject

Name of document indicates subject

Author and short title of source (no page number for electronic source)

Author and short title of source (no page number for electronic source)

Direct quotation

Direct quotation

Using paraphrases

Using paraphrases

A paraphrase accurately states all the relevant information from a passage in your own words and sentence structures, without any additional comments or elaborations. A paraphrase is useful when the main points of a passage, their order, and at least some details are important but—

To paraphrase without plagiarizing inadvertently, do not simply substitute synonyms, and do not imitate an author’s style. If you wish to cite some of an author’s words within a paraphrase, enclose them in quotation marks. The following examples of paraphrases resemble the original either too little or too much:

ORIGINAL

Language play, the arguments suggest, will help the development of pronunciation ability through its focus on the properties of sounds and sound contrasts, such as rhyming. Playing with word endings and decoding the syntax of riddles will help the acquisition of grammar. Readiness to play with words and names, to exchange puns and to engage in nonsense talk, promotes links with semantic development. The kinds of dialogue interaction illustrated above are likely to have consequences for the development of conversational skills. And language play, by its nature, also contributes greatly to what in recent years has been called metalinguistic awareness, which is turning out to be of critical importance in the development of language skills in general and of literacy skills in particular.

—DAVID CRYSTAL, Language Play (180)

UNACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE: STRAYING FROM THE AUTHOR’S IDEAS

Crystal argues that playing with language—

This paraphrase starts off well enough, but it moves away from paraphrasing the original to inserting the writer’s ideas; Crystal says nothing about learning new languages or pursuing education.

UNACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE: USING THE AUTHOR’S WORDS

Crystal suggests that language play, including rhyme, helps children improve pronunciation ability, that looking at word endings and decoding the syntax of riddles allows them to understand grammar, and that other kinds of dialogue interaction teach conversation. Overall, language play may be of critical importance in the development of language and literacy skills (180).

Because the highlighted phrases are either borrowed from the original without quotation marks or changed only superficially, this paraphrase plagiarizes.

UNACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE: USING THE AUTHOR’S SENTENCE STRUCTURES

Language play, Crystal suggests, will improve pronunciation by zeroing in on sounds such as rhymes. Having fun with suffixes and analyzing riddle structure will help a person acquire grammar. Being prepared to play with language, to use puns and talk nonsense, improves the ability to use semantics. These playful methods of communication are likely to influence a person’s ability to talk to others. And language play inherently adds enormously to what has recently been known as metalinguistic awareness, a concept of great magnitude in developing speech abilities generally and literacy abilities particularly (180).

Although this paraphrase does not rely explicitly on the words of the original, it does follow the sentence structures too closely. Substituting synonyms while keeping the original paragraph structure is not enough to avoid plagiarism. The paraphrase must represent your own interpretation of the material and thus must show your own thought patterns.

Here are two paraphrases of the same passage that express the author’s ideas accurately and acceptably, the first completely in the writer’s own words and the second, from David Craig’s notes (32e), including a quotation from the original.

ACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE: IN THE STUDENT WRITER’S OWN WORDS

Crystal argues that playing with language—

ACCEPTABLE PARAPHRASE: QUOTING SOME OF THE AUTHOR’S WORDS

Crystal argues that playing with language—

Using summaries

Using summaries

A summary is a significantly shortened version of a passage or even of a whole chapter or work that captures main ideas in your own words. Unlike a paraphrase, a summary uses just the main points of a source. Your goal is to keep the summary as brief as possible without distorting the author’s meaning.

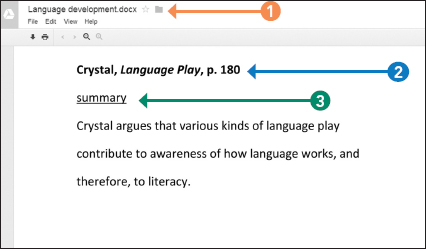

Here is David Craig’s note recording a summary of the Crystal passage. The note states the author’s main points selectively—

Subject heading

Subject heading

Author, title, page reference

Author, title, page reference

Summary of source

Summary of source

Taking other kinds of notes

Taking other kinds of notes

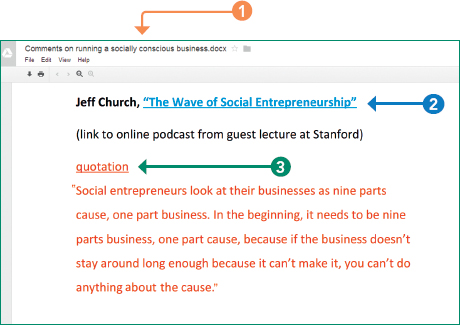

Many researchers take notes that don’t fall into the categories of quotations, paraphrases, or summaries. Those who work with media sources, especially, need alternatives. Some researchers take key-

David Craig’s notes

As part of his study on messaging language and youth literacy, David Craig analyzed messaging conversations and kept notes on each occurrence of nonstandard English spellings and words and their frequencies. Since he was attempting to categorize these occurrences as well as quantify them, he labeled each note with the type of change that he was noticing. David’s notes not only helped him synthesize his data; they also made it easier for him to present the data in a clear, concise chart (32e). Researchers also take field notes, which record their firsthand observations or the results of their surveys or interviews (11e).

Whatever form your notes take, be sure to list the source’s title, author, and a way to find the information again, such as page number(s), links, or time codes. In addition, check that you have carefully distinguished your own thoughts and comments from those of the source itself.

Annotating source material

Annotating source material

Sometimes you may photocopy or print out a source you intend to use. In such cases, you can annotate the photocopies or printouts with your thoughts and questions and highlight interesting quotations and key terms. You can also use video or audio annotation tools to take notes on media sources.

If you take notes in a computer file, you may be able to copy online sources electronically, paste them into the file, and annotate them there. Try not to rely too heavily on copying or printing out whole pieces, however; you still need to read the material very carefully. Also resist the temptation to treat copied material as notes, an action that could lead to inadvertent plagiarizing. (In a computer file, using a different color for text pasted from a source will help prevent this problem.)