29c Using varieties of English to evoke a place or community

“Ever’body says words different,” said Ivy. “Arkansas folks says ’em different from Oklahomy folks says ’em different. And we seen a lady from Massachusetts, an’ she said ’em differentest of all. Couldn’ hardly make out what she was sayin’.”

—JOHN STEINBECK, The Grapes of Wrath

Using the language of a local community is an effective way to evoke a character or place. Author and radio host Garrison Keillor, for example, peppers his tales of his native Minnesota with the homespun English spoken there: “I once was a tall dark heartbreaker who, when I slouched into a room, women jumped up and asked if they could get me something, and now they only smile and say, ‘My mother is a big fan of yours. You sure are a day-

Weaving together regionalisms and standard English can also be effective in creating a sense of place. Here, an anthropologist writing about one Carolina community takes care to let the residents speak their minds—

For Roadville, schooling is something most folks have not gotten enough of, but everybody believes will do something toward helping an individual “get on.” In the words of one oldtime resident, “Folks that ain’t got no schooling don’t get to be nobody nowadays.”

—SHIRLEY BRICE HEATH, Ways with Words

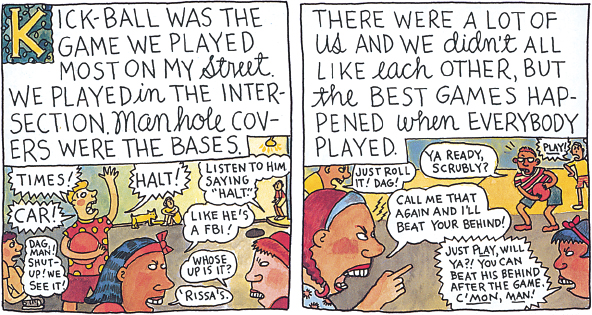

Varieties of language can also help writers evoke other kinds of communities. In this panel from One! Hundred! Demons!, Lynda Barry uses playground language to present a vivid image of remembered childhood games. See how kids’ use of slang (“Dag”) and colloquialisms (“Whose up is it?”) helps readers join in the experience.

For Multilingual Writers: Global varieties of English