30d Using figurative language

Contents:

Using similes

Using metaphors

Using analogies

Avoiding clichés and mixed metaphors

Using allusions

Signifying

Figurative language, or figures of speech, can paint pictures in our minds, allowing us to “see” a point readily and clearly. For example, an economist might explain that if you earned one dollar per second, you would need nearly thirty-

In important ways, all language is metaphoric, referring to something beyond the word itself for which the word is a symbol. Particularly helpful in building understanding are specific types of figurative language, including similes, metaphors, and analogies.

Using similes

Using similes

Similes use like, as, as if, or as though to make an explicit comparison between two things.

Rain slides slowly down the glass, as if the night is crying.

—PATRICIA CORNWELL

You can tell the graphic-

—PETER SCHJELDAHL

Using metaphors

Using metaphors

Metaphors are implicit comparisons, omitting the like, as, as if, or as though of similes.

The Internet is the new town square.

—JEB HENSARLING

Often, metaphors are more elaborate.

Black women are called, in the folklore that so aptly identifies one’s status in society, “the mule of the world,” because we have been handed the burdens that everyone else—

—ALICE WALKER, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens

Using analogies

Using analogies

Analogies compare similar features of two dissimilar things; they explain something unfamiliar by relating it to something familiar. Analogies are often several sentences or paragraphs in length. Here, the writer draws an analogy between corporate pricing strategies and nuclear war:

One way to establish that peace-

—JAMES SUROWIECKI

Before you use an analogy, make sure that the two things you are comparing have enough points of similarity to justify the comparison.

Avoiding clichés and mixed metaphors

Avoiding clichés and mixed metaphors

Just as effective figurative language can create the right impression, ineffective figures of speech—

A cliché is a frequently used expression such as busy as a bee or children are the future. By definition, we use clichés all the time, especially in speech, and many serve usefully as shorthand for familiar ideas. If you use too many clichés in your writing, however, readers may conclude that what you are saying is not very new or interesting—

Since people don’t always agree on what is a cliché and what is a fresh image, how can you check your writing for clichés? Here is a rule to follow: if you can predict exactly what the upcoming word(s) in a phrase will be, it is probably a cliché.

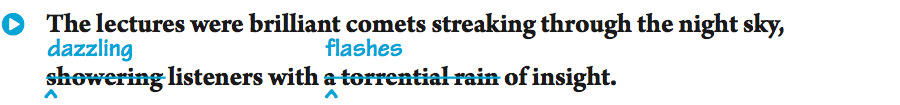

Mixed metaphors are comparisons that are not consistent. Instead of creating a clear impression, they confuse the reader by pitting one image against another.

The images of streaking light and heavy precipitation are inconsistent; in the revised sentence, all of the images relate to light.

Using allusions

Using allusions

Allusions are indirect references to cultural works, people, or events. When a sports commentator said, “If the Georgia Tech men have an Achilles heel, it is their inexperience, their youth,” he alluded to the Greek myth in which the hero Achilles was fatally wounded in his single vulnerable spot, his heel.

You can draw allusions from history, literature, sacred texts, common wisdom, or current events. Many movies and popular songs are full of allusions. The Simpsons episode called “Eternal Moonshine of the Simpson Mind,” for example, alludes to the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Remember, however, that allusions work only if your audience recognizes them.

Signifying

Signifying

One distinctive use of figurative language found extensively in African American English is signifying, in which a speaker cleverly needles or insults the listener. In the following passage, two African American men (Grave Digger and Coffin Ed) signify on their white supervisor (Anderson), who ordered them to discover the originators of a riot:

“I take it you’ve discovered who started the riot,” Anderson said.

“We knew who he was all along,” Grave Digger said.

“It’s just nothing we can do to him,” Coffin Ed echoed.

“Why not, for God’s sake?”

“He’s dead,” Coffin Ed said.

“Who?”

“Lincoln,” Grave Digger said.

“He hadn’t ought to have freed us if he didn’t want to make provisions to feed us,” Coffin Ed said. “Anyone could have told him that.”

—CHESTER HIMES, Hot Day, Hot Night

Coffin Ed and Grave Digger demonstrate the major characteristics of effective signifying: indirection, ironic humor, fluid rhythm—

For Multilingual Writers: Mastering idioms