CHAPTER 4: Getting Started with the Task Schedule

Chapter 4

Getting Started with the Task Schedule

The task schedule, which has been mentioned several times in previous chapters, is the most important document a team produces for managing itself. A task schedule keeps the team on track by documenting who does what by when. Moreover, a task schedule helps the team plan the details of the project so that there are no surprises at the end. This chapter takes you through the steps of producing a task schedule that will help your team implement a layered collaboration. This chapter focuses on four steps:

- Identifying major tasks

- Assigning tasks to team members

- Scheduling the tasks in layers, providing multiple opportunities to comment or revise one another’s work

- Balancing the workload

Identifying Major Tasks

The first step in producing a task schedule is to brainstorm the major tasks that the team will have to perform. Resist assigning tasks to individual team members at this point. Instead, concentrate on making sure that all parts of the project are covered. Listing tasks is a brainstorming activity and is appropriate for face-to-face collaboration.

For example, a team working on a scientific research report might identify the following tasks:

Project management

Collect data

Write

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Abstract

Initial topic proposal

Works cited

A team working on a proposal might identify the following tasks:

Project management

Research

Identify audience needs and all relevant stakeholders

Identify problems with status quo and collect documentation of problems

Investigate potential solutions and costs

Write

Statement of problem and justification for proposal

Overview of options

Cost-benefit analysis and breakdown

Recommendation and rationale

Cover letter

Executive summary

Create presentation slides

Rehearse and deliver final presentation

A team creating a Web site might identify the following tasks:

Project management

Write initial topic proposal

Research client

Obtain technical information for site from client

Find out client’s needs and preferences for the site

Design

Site layout (number of links or sections on home page)

Home page layout

Content page layout

Graphics

Revise content from client for consistency, Web-friendliness

Assemble the site on test server

Test and revise the site

Create usability script and set up tests

Run tests with three users for usability, broken links

Make revision tests

Upload to live site

Write instructions for maintaining the site

Write final report for instructor

As the differences in these three task lists demonstrate, your task list needs to be specific to your team’s project. Some projects will consist primarily of research and writing; other projects will involve additional components, such as preparing presentations, uploading Web sites, or coordinating with other people and teams. Be sure to read your assignment guidelines carefully, and work together with your team to come up with a complete list of tasks. The more complete your list is now, the less you will have to figure out on the spur of the moment later.

Assigning Roles: Motivation versus Experience

Christopher Avery, a consultant on leadership and teamwork, states that when a team assigns roles, matching motivation is far more important than matching skills: “If members don’t have the required skills, a high performance team will improvise. The same is not true for motivation, however. Every team performs to the level of its least invested member” (2001). In other words, it is more important to assign team members to tasks that they are motivated to learn or do than to tasks with which they already have experience.

One of the biggest problems with layered collaboration in educational settings is that team members often divide up tasks by expertise (that is, the most experienced writer does most of the writing; the most experienced technical person does most of the computer work) rather than by what will make for the best learning experience. Although this division certainly makes sense and is efficient, it also limits team members’ opportunities to develop skills in their weak spots. Team members need to take responsibility for making their time on the project a productive learning experience. Such “on the job” training mirrors the corporate world, where managers will sometimes assign tasks to particular workers in order to make them better-rounded employees.

Not only does dividing tasks up by motivation rather than experience benefit individual team members, but it may also benefit the team. Often, a motivated novice will perform at least as well as a bored expert, especially if the novice can contact an expert as a resource for specific questions. An expert who is bored with a task will put in less effort and be less receptive to the team’s feedback than a novice who is eager to show that he or she is able to do the job.

Teams can avoid having to choose between motivation and experience by assigning members a primary task that they are motivated to learn and a secondary, advisory task that makes use of their existing expertise. The assignment of a secondary task allows each team member to serve as an adviser or primary “go to” person in case another team member completing a given task has questions or runs into difficulties. This structuring is similar to that of workplace teams, in which experienced employees focus on gaining new, more complex skills while at the same time helping newer employees learn more routine skills.

For example, if someone on your team has done numerous PowerPoint presentations or has years of experience writing proposals, this person should serve as an adviser to another team member who is eager to learn this skill. Not only will the novice be able to draw on the expert’s advice, but the expert will also have the opportunity to consolidate his or her knowledge on the topic by teaching someone else. Novices often ask interesting questions that challenge more experienced colleagues to reexamine what they think they know and approach the problem from a new perspective. This explains the adage “If you want to truly learn something, then teach it!”

Assigning roles by motivation rather than experience may also help your team avoid a problem that is particularly common in student teams: a gendered division of labor, in which women complete writing tasks and men complete technical work. This tendency is at least partly due to a culture that associates tools and equipment with men and language skills with women and is often reinforced on student teams, particularly when team members do not know one another well. Assigning tasks according to what team members want to learn rather than what they already know how to do can help a team break out of traditional, gendered role assignments.

As a team, review the team preparation worksheets that team members completed in Chapter 3, “Getting Started with the Team Charter” (see Figure 3.1), examining what each person perceived as his or her strengths and learning goals for the project. Then discuss how to arrange the project so that motivated teammates can acquire new skills while still having the security of a more experienced adviser who can answer questions or help out if they get “stuck.” This information about primary and secondary roles (and any concerns about these roles) should be added to the team charter.

Scheduling the Tasks

Once your team has assigned primary and secondary roles and recorded these in the charter, look over the team preparation worksheets (Figure 3.1) and team charter again to refresh your memory about any scheduling concerns the team needs to keep in mind. Be sure to also review all of the instructor’s deadlines in the assignment guidelines.

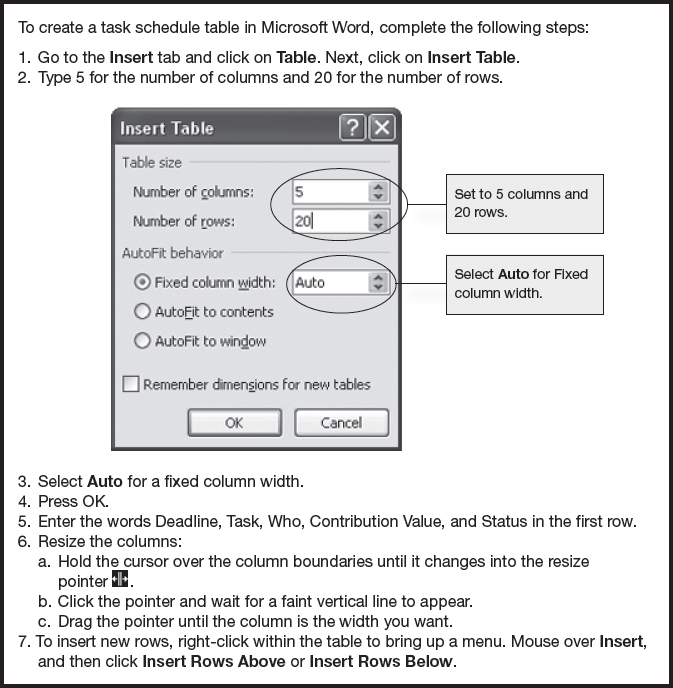

The project manager should prepare a rough draft of the task schedule, being sure to include plenty of opportunities for team members to revise and comment on one another’s work. Although you can find complicated project-management software for maintaining an updated task schedule, a simple table prepared as a word-processing document or a spreadsheet is just as effective for most school projects. Figure 4.1 gives instructions for creating a task schedule in Microsoft Word. Download a spreadsheet formatted for a task schedule.

Once the project manager has created a rough draft of the task schedule, he or she should send it to team members for review before their next meeting. This gives them a chance to reflect on the task schedule and think of ways it might be improved. At the next meeting, the team can work together to revise the schedule to everyone’s satisfaction and assign contribution values (discussed in the next section).

Balancing the Workload

One of the biggest problems with collaboration in student teams is the unequal division of labor. Unequal division of labor is also present in workplace settings, but typically this is not a problem because it is common for employees to dedicate different amounts of time or effort to a project. In the classroom, however, the assumption usually is that everyone will contribute equally to the project. Thus, student teams have a challenge not often found in workplace teams: distributing the workload so that everybody contributes roughly equally to the project.

To help balance the workload fairly, the team can work together to estimate a contribution value for each task. Contribution values can be measured on a five-point scale (where 5 = difficult, time-consuming task critical to group success and 1 = relatively easy, noncritical task). These contribution values can then be totaled for each team member to get an approximation of how much everyone is contributing to the group. The goal should be for each team member to contribute roughly equivalent amounts (unless one team member has negotiated to receive a lower grade in exchange for less work—see Chapter 3, “Getting Started with the Team Charter”).

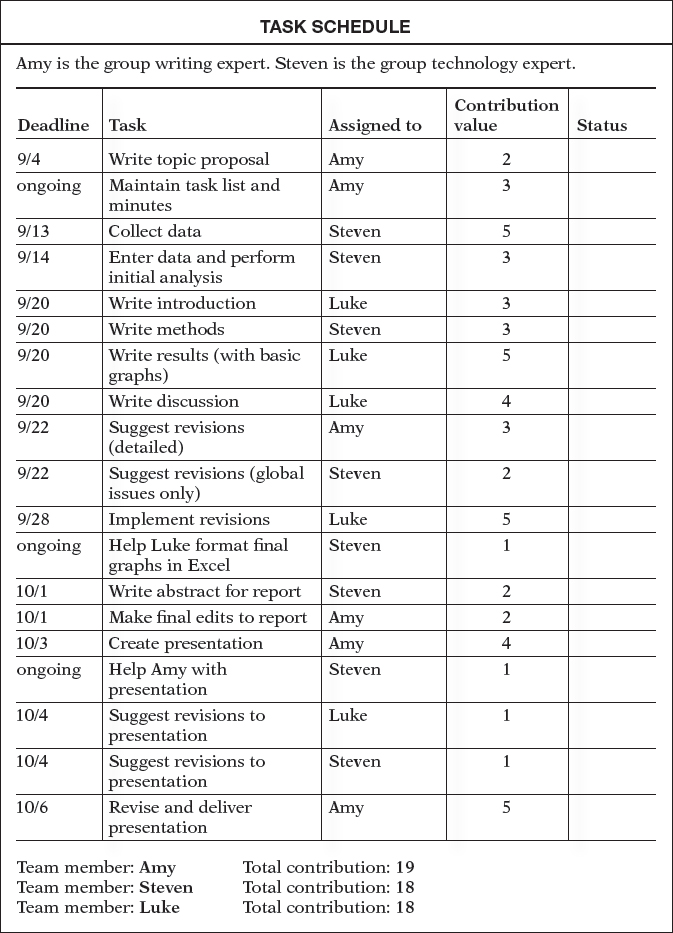

Figure 4.2 shows one team’s task schedule worksheet. Each task is clearly assigned to a team member and has a clear-cut deadline. In addition, each task has a contribution value that the team has agreed on. When the contribution values are totaled, it is clear that all three team members are doing roughly equivalent work but that Amy is doing slightly more than the other two team members. Thus, if additional tasks should come up during the project, Steven and Luke should volunteer for those tasks.

Common Mistakes Students Make When Assigning Contribution Values

Your instructor will probably look over your task schedule and the contribution values your team has assigned in order to make sure that the team is crediting work appropriately. Student teams tend to underestimate the amount of effort required to produce good writing (which often requires substantial revision) and to overestimate the amount of effort associated with technology tasks. Be aware of these tendencies when your team assigns values.

Technology and Tools for Task Schedules

To maintain the task schedule for short projects, teams should probably use familiar and uncomplicated tools such as tables created with a word-processing program or spreadsheets. However, when projects are long and complex, your team may benefit from using more sophisticated scheduling and project-management tools. Following is a brief overview of common tools for keeping track of projects.

Gantt Charts

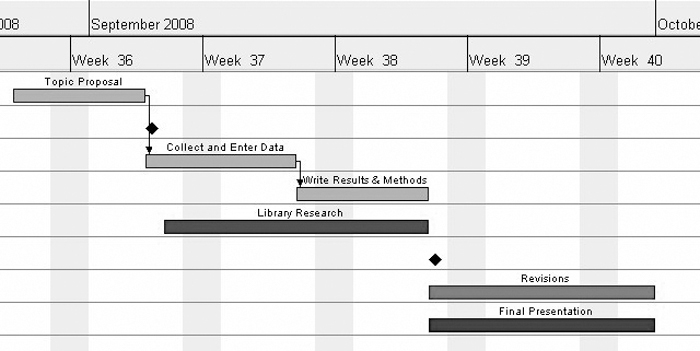

A Gantt chart is a type of horizontal bar chart for visualizing the start and end dates of various tasks on a project (see Figure 4.3). Some Gantt charts even show dependencies (when starting one task depends on completing an earlier task). Gantt charts are particularly popular in software development.

One drawback of Gantt charts is that they do not show the complexity of the individual tasks—or the amount of team resources required to complete these tasks—and thus may not provide an accurate representation of the project workload.

Project-Management Software

Many companies purchase project-management software to help supervisors keep track of multiple ongoing projects. These tools often have built-in Gantt charts and other scheduling features as well as tools for adjusting employee workloads and allocating company resources. One of the most popular (and most expensive) options is Microsoft Project. Project-management software is rarely free, but many software companies offer free preview trials. Because most project-management software is built with the upper-management company executive in mind, it may be overkill for your school-based project.

Wikis

A wiki is a collection of Web pages that allows those with access to make changes and add new pages. Teams can place a copy of the task schedule on a private wiki that all team members can update to note when items are completed. Most wikis have a revision-history feature that allows the team to track any changes made. The team can also use the wiki to store other documents, such as assignment instructions and PDFs related to the project. (Note: A Web-based editor such as Google Docs has similar functionality but does not allow teams to store external documents. See Chapter 6, “Revising with Others,” for more information on tools that help you collaborate.)

Work Cited

Avery, C., with Walker, M. A., & O’Toole, E. (2001). Teamwork is an individual skill: Getting your work done when sharing responsibility. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.