CHAPTER 3: Getting Started with the Team Charter

Chapter 3

Getting Started with the Team Charter

Kelly and Sean were both members of a four-person team working on a Web site. They made the following observations:

Kelly: Sean has done nothing. We asked him to do the first draft of the project proposal by compiling all of our information into a paper. Instead, he came up with less than one page that didn’t meet the requirements of the proposal at all. This is really pitiful since we gave him over four pages of our own work to build on. Also, he was supposed to add what research he had done to the proposal, and there was no mention of it, so I’m assuming that he hasn’t done any research. We ended up using the research that Eli got from his interview. Sean has showed up to every meeting; however, he has added nothing during any of the meetings. In fact, during the last meeting, he was chatting on Instant Messenger on his laptop while we were all discussing and working on the project proposal. . . . In the last week, he has finally shown some interest in helping out, but I’m reluctant in giving him anything important to do as he has so far proven himself unreliable.

Sean: I haven’t spent much time at all on the project, sadly. As far as I’m aware, Kelly is the only one who’s done much the last two weeks, though I could be wrong — it wouldn’t be the first time I’ve missed something obvious during this project. . . . The rest of the team seems to work together excellently, but I’ve felt ignored a few times. I completely missed part of the requirement of the proposal, and instead of saying anything to me, Eli and Angela just completely rewrote it. I’ve also felt ignored during meetings and thus have been mostly silent during group reviews of papers, which would ordinarily be my strongest moments. . . . Everything that I’ve done so far on the project has been incredibly subpar by my own standards. I’ve done two writing assignments, and both times, I only noticed a fraction of the instructions we were given. . . . Much of the time I felt confused as to what was going on. This was my own fault — for the first few weeks of the project, I was highly unmotivated. At the time I’m writing this, though, I think I’m about to be given some content to make a page for, so that’s not as bad as it could be.

Before you continue reading, take a moment to think about what this team could have done to prevent the problems that it experienced. How would you characterize the problems with this team?

The Team Charter: An Ounce of Prevention Is Worth a Pound of Cure

At the start of a project, the team is usually eager to charge ahead and start productive work right away. However, teams do well to bear in mind the slogan “Failing to plan is planning to fail.” A team that spends an hour at the very beginning of the project discussing goals, expectations, and team norms can save substantial time and stress later on in the project.

Many experienced practitioners in a range of fields recommend that teams develop a team charter in the first meetings. A team charter is a brief, informal document that describes the “big picture” goals and priorities of the project. The official purpose of a team charter is to have a written statement of the team’s priorities and norms that the team can use to resolve any problems or confusion that may occur later in the project. The unofficial purpose, particularly when team members have not worked together before, is to air any differences that they might have in goals, expectations, and commitment levels before the project begins.

For instance, if your project involves a client outside of the classroom, you may find that some team members put a priority on meeting the client’s expectations, whereas others prioritize according to the instructor’s exact directions. Similarly, you may find that team members have different ideas about the effort they are willing to invest in the project. It is better to know about these differences up front rather than discover them later on.

In general, the bigger the project, the more important the team charter is. Team charters differ greatly in content and format depending on the type of organization and project. For student projects, an effective team charter should contain the following information:

- Overall, broad team goals for the project

- Measurable, specific team goals

- Personal goals

- Individual level of commitment to the project

- Other information about team members that may affect the project

- Statement of how the team will resolve impasses

- Statement of how the team will handle missed deadlines

- Statement of what constitutes unacceptable work and how the team will handle this

Because the team charter is an internal document (something that will be seen only within the team) and because the real point of a team charter lies in discussing it rather than in writing it, this document can be composed in a face-to-face setting. The goal of the team charter is to uncover and discuss potential problems in a low-key setting, before any work has been assigned.

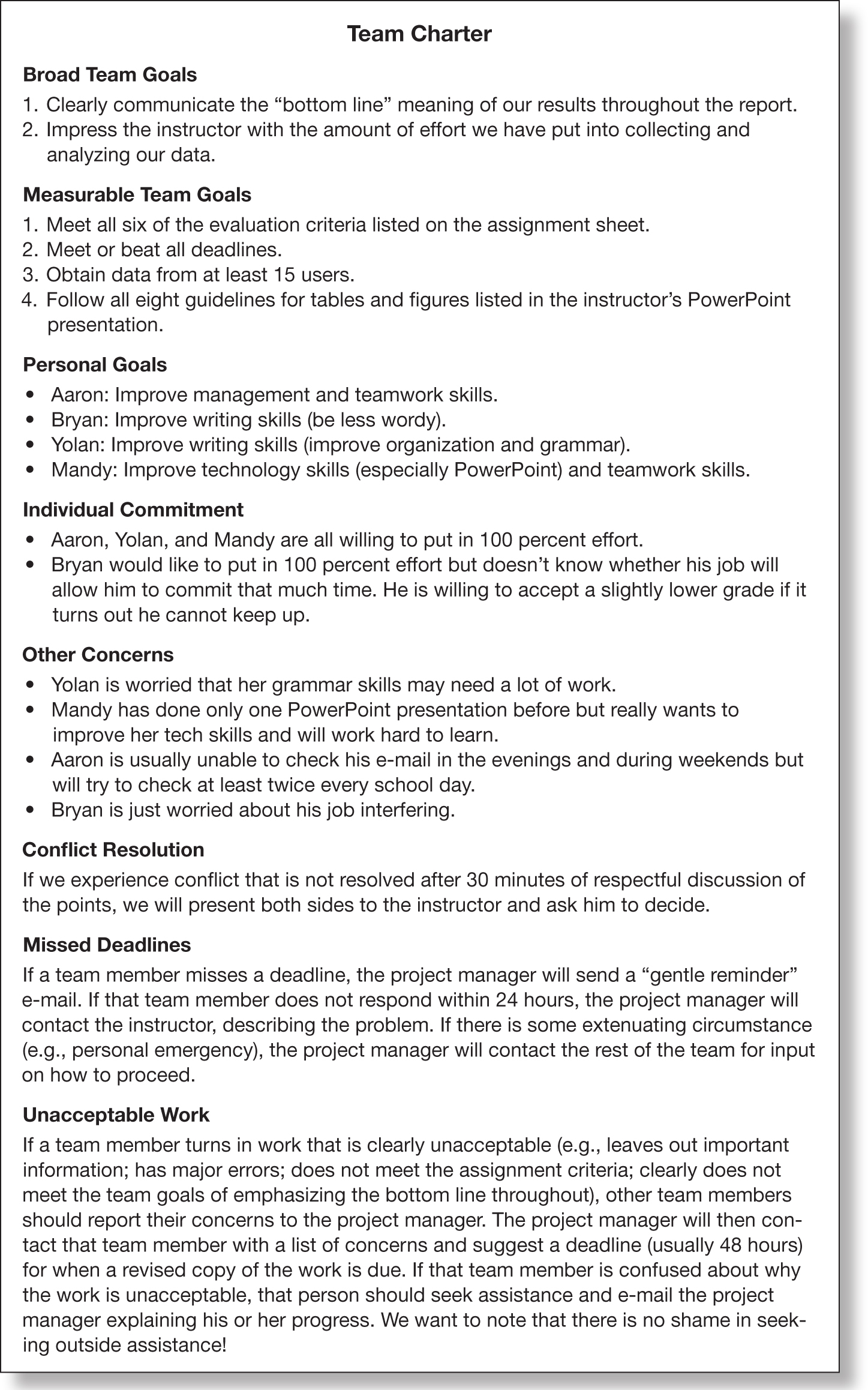

This chapter discusses what goes into a team charter. Before you start working on the charter with your group, take a moment to honestly assess your background, goals, and preparation for this project by completing the team preparation worksheet in Figure 3.1. You can also download a copy of this worksheet.

Team Goals: What Constitutes Success?

Your first action as a team should be to agree on what defines a successful project. Spend a few minutes discussing the one or two top broad goals you have for the project. Examples of broad goals include:

- Making an original argument

- Presenting our data accurately and effectively

- Persuading the audience to accept our solution

- Following the format and guidelines of the assignment sheet precisely

- Designing a product that satisfies the client

- Creating instructions that a computer novice can follow without mistakes

Do not simply list “getting an A” as one of your priorities. Instead, try to break down what criteria are most important to meet in order to receive an A. It may be that one person believes that getting an A means satisfying the client while another team member believes it means finding an original solution to a problem (whether or not the client wants an original solution). Again, the goal here is to uncover any fundamental differences about what the team is trying to accomplish before you start.

Measurable Goals: How Can You Measure Success?

After your team has set out goals about what defines success, you need to translate your broad goals into measurable goals with objective, specific criteria that are clearly either met or not met. Creating measurable goals is an essential step in workplace teams, which might come up with goals such as increasing productivity by 20 percent or reducing accidents by at least 40 percent. These goals are specific, objective, and measurable: they can be listed as numbers, so there should be little disagreement over whether or not they are met. Student teams may have more difficulty in generating measurable goals because projects are smaller and fewer external, objective measures are available. Nevertheless, creating measurable goals is an important skill that you should begin to practice now.

Examples of measurable goals include:

- Meeting all 10 of the assignment sheet’s guidelines for the report’s format

- Meeting or beating all the deadlines set out in the task schedule

- Reducing the word count by 15 percent between the rough draft and the final draft by eliminating wordiness and repetitiveness without deleting any content

- Writing instructions clearly enough that novice users voice no more than two questions or instances of confusion during usability testing

- Creating a Web site that four out of five classmates rank as user-friendly in anonymous surveys

- Citing at least four sources in the works cited page

- Having fewer than one grammatical error or typo per page

Although “getting an A” is a measurable goal, it is not a useful one because the team will not know whether this goal has been achieved until after the project has been completed, at which point it is too late to act on this goal. Instead, try to define measurable goals that can serve as a checklist before turning in the project.

Personal Goals: What Do Team Members Want Out of the Project?

Next, try to uncover what is most important to each member of the team. Examples of personal goals are:

- Improving my writing skills

- Learning how to create a visually compelling PowerPoint presentation

- Creating a document that I can talk about on job interviews

- Having a productive and friendly team experience

- Completing the project with as little effort as possible

This last goal will almost certainly bring you into conflict with other team members, who will understandably wonder if they can trust you. However, there is some benefit to acknowledging this up front in order to avoid becoming a negative contributor (see the section “Negative Contributors”).

Understanding what each team member hopes to gain personally from the project will help the group in the next step of defining and assigning roles and tasks. These statements of personal investment in the project should also help the group to determine specific directions for the project.

Individual Commitment: How Much Effort Will Each Person Invest?

In addition to discussing project goals, team members should also discuss their degree of commitment to these goals. Do different team members have different ideas about the amount of time and effort that is needed to succeed? Is everyone truly willing to invest the effort needed to get a good grade on the project? Does everybody feel equally strongly about the importance of getting an A?

Many texts on teamwork assume that everyone on the project will have total commitment to the project — or else can be motivated to contribute 100 percent with just a little prodding. However, in reality, team members have responsibilities outside of the project and different levels of commitment and internal motivation. By frankly discussing what each person is able or willing to contribute up front, teams can anticipate and avoid potential problems.

The team has some concrete options for dealing with team members who have low commitment levels:

- Team members with low commitment can be assigned fewer or less critical tasks on the project so that if they do not follow through, other team members can pick up the slack.

- The team can consider formalizing an arrangement in which one team member negotiates to do less work in exchange for a lower grade. For instance, the team charter might state that John Doe will contribute approximately 25 percent less work than other team members and consequently will receive a one-letter grade reduction on the project. (Check with your instructor to see if this is an option.)

Simply knowing that a particular team member has low motivation can often protect the team against surprises and extreme resentment later on in the project.

Situations in which team members contribute unequal amounts of effort mirror conditions that you might find in the workplace. In work-based teams, one or two team members often may be committed full-time to a project while others have other work priorities and contribute at a much lower level.

Other Information: What Other Factors Might Affect Performance?

Do you have a personal commitment that will make you unavailable during a particular time frame? Do you have a pending personal emergency that may make you less dependable than you are normally? Are you worried that you will have difficulty meeting your team’s expectations for the quality of the work? You should express these concerns and potential limitations at the beginning of the project so that you don’t become a negative contributor to the group — someone whose presence hurts the team more than it helps.

If the team knows about shortcomings or potential obstacles up front, it can work these constraints into the task schedule. For instance, Cynthia was asked to draft a proposal but had little experience with this type of writing. The team responded by scheduling an extra round of early feedback so that Cynthia could be sure she was going in the right direction. Similarly, Jiang was worried that his poor English skills might hurt the team. The team was able to plan for this by scheduling additional time for Jiang to visit the school’s writing center and receive feedback on his grammar before submitting his material to the group.

By understanding your needs and preferences before you start working on a team, you can recognize when your roles and responsibilities on the team are in conflict with your individual needs. Learning to recognize those conflicts and to positively address them represents one of the strongest opportunities for growth that people receive from working in teams.

Negative Contributors

Chris: I think everyone noticed that Stephanie felt like an outsider within the group. This is entirely her fault. If Stephanie would have attended class like she said she would, then we wouldn’t have a problem with her feeling left out. . . . Our presentation is only five days away. Stephanie doesn’t have a freakin’ clue what is going on. . . . I don’t know what she feels she is contributing, but it isn’t that much.

Stephanie is a negative contributor because rather than helping her team finish the project, she has created an additional problem for her teammates to solve. Similarly, Sean (described at the beginning of this chapter) is also a negative contributor. Negative contributors include those who miss deadlines or meetings, turn in substandard work, or engage in unproductive conflict that does not further group goals.

Groups do have options for handling negative contributors: they can be removed from the team by the instructor, or they can receive poor evaluations from their teammates at the end of the project that translate into a lowered project grade. Of course, these are worst-case scenarios — if possible, it is better to prevent these negative scenarios from occurring.

The best way to avoid becoming a negative contributor is to be honest about your skills and commitments at the beginning of the project. For instance, if you know you will be able to dedicate only a limited number of hours a week or that your skills in a particular area are weak, tell the team about these constraints up front. The team can then factor these constraints into the task schedule. Similarly, if the team knows that you are inexperienced with a particular technology needed for the project, such as FrontPage, someone more experienced can be assigned as your “backup” in case you need to ask for help.

A good, clear task schedule with plenty of overlapping responsibilities and “padding” (extra space in the project for missed deadlines or emergencies) can help prevent any problems that negative contributors might cause. The clear task schedule lets team members know immediately when a task has not been completed, and the padding gives the team a chance to recover in a worst-case scenario.

Irreconcilable Differences: How Will the Team Resolve Impasses?

Chapter 5, “Constructive Conflict,” discusses the benefits of constructive conflict and why teams benefit from the healthy debate of ideas. However, there will be times when teams are unable to resolve their disagreements. A team charter that details when and how the team will handle impasses, or stalemates, will help the team progress even in the face of disagreement. The team charter should contain a brief one- or two-sentence statement of how the team will resolve continuing disagreements and at what point (two meetings, 30 minutes of discussion) the team will pursue the resolution method. Table 3.1 describes the four basic methods for resolving impasses and their advantages and disadvantages.

Table 3.1. Four methods for resolving impasses

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Consensus: Discuss the issue until everyone agrees. |

|

|

| Majority rules: Vote and adopt the majority decision. |

|

|

| Instructor decides: Present both sides anonymously to the instructor and let him or her decide. |

|

|

| Third party decides: Present both sides anonymously to a classmate, a client (if applicable), or another party and ask that person to decide. |

|

|

Late Work: How Will the Team Handle Missed Deadlines?

Missed deadlines signal a lack of commitment and a breach of trust. Team members rely on one another to make commitments; if a team member fails to honor a commitment, other group members will assume that the person is not trustworthy.

Teams should decide in advance how they will handle missed deadlines. Having procedures in place helps prevent the situation because team members will know there are clear consequences to their actions and also helps defuse the situation if it does occur.

The team charter should spell out how to handle missed deadlines. The following examples show some typical wording:

- The project manager e-mails a reminder to the team member who is late. If the team member does not respond within 24 hours, the project manager contacts the instructor. If the team member does respond with a valid excuse and a reasonable deadline, the project manager informs the rest of the team of the new deadline.

- The project manager e-mails a reminder to the team member who is late. If the team member does not submit acceptable work within 24 hours of this e-mail, the project manager contacts the rest of the team, explaining the situation and asking for input on how to proceed.

See Chapter 8, “Troubleshooting Team Problems,” for more information on dealing with tardiness.

Unacceptable Work: How Will the Team Handle Poor-Quality Contributions?

Sometimes, team members meet deadlines but submit work that is clearly unacceptable because it lacks important required information, falls considerably short of the page requirements, is riddled with grammatical errors, or has other shortcomings. Dealing with unacceptable work is often more stressful for the team than coping with missed deadlines because deciding what is unacceptable requires judgment and sometimes awkward discussions.

The team charter should list some general criteria for unacceptable work (for example, rough drafts missing more than 25 percent of the required information; near-final drafts that do not meet all of the assignment criteria), a plan for notifying a team member that the work is unacceptable, and a recommended deadline for revising unacceptable work. Criteria for unacceptable work should distinguish between rough drafts that the team will subsequently revise and more finished work produced closer to the final project deadline. Table 3.2 lists some ways of handling unacceptable work, along with their advantages and disadvantages.

Putting It All Together

A team charter not only helps the team plan for negative situations but also prevents these situations from occurring in the first place because team members (1) have a nonthreatening place to voice concerns about the project and (2) are aware that there are clear consequences for letting the team down. A calm discussion about how the team will handle hypothetical missed deadlines is much less stressful and time-consuming than panicking at the last minute over how to proceed when one or more teammates have not done their work.

Table 3.2. Methods for responding to a member who has produced unacceptable work

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Project manager says nothing: Project manager asks another team member to rewrite a section (or does it himself or herself) and says nothing to the person directly. |

|

|

| Project manager decides: Project manager reviews all work to see if it meets acceptability criteria; contacts anyone who produces unacceptable work; and gives that person suggestions for improvement and a 48-hour deadline to revise. |

|

|

| Team decides: All team members review the work and e-mail the project manager, who then communicates the concerns (without mentioning names) to the person with a 24-hour deadline to revise. |

|

|

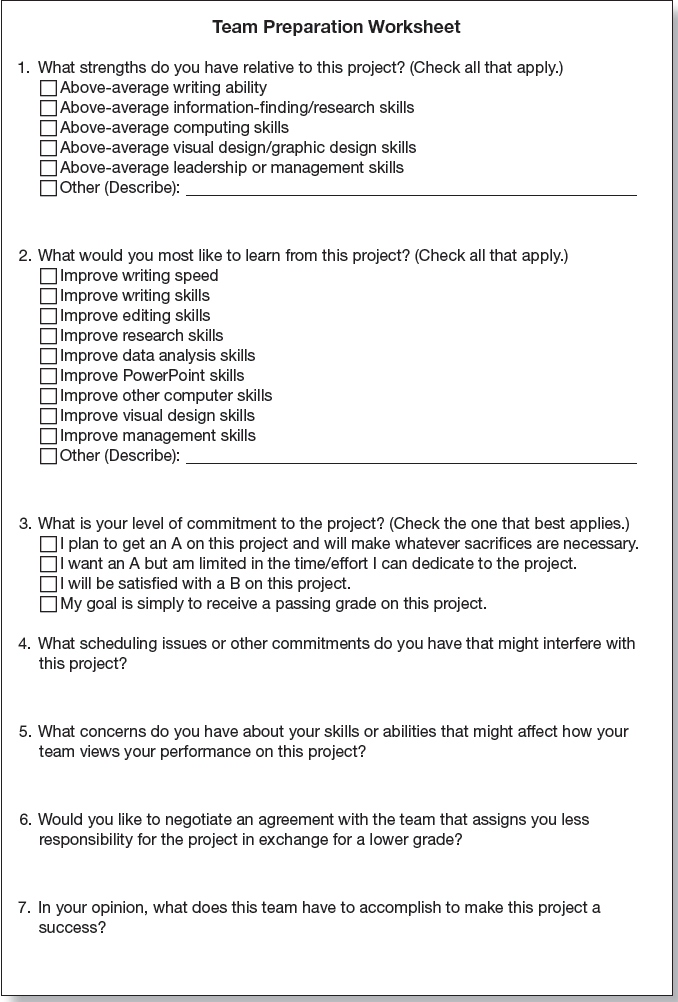

Figure 3.2 illustrates a team charter. Note that the tone is informal and that the charter makes good use of formatting (including boldface headings and bulleted and numbered lists) to make information easy to find. The team charter should be stored in a central place (and/or e-mailed to the entire team) so that team members can use it for reference.