CHAPTER 8: Troubleshooting Team Problems

Chapter 8

Troubleshooting Team Problems

In my research on teamwork, more than half of the student teams I observed ran into at least one major breakdown in the course of their project. Although following the advice in this book will help your team avoid many of these breakdowns, problems undoubtedly will still occur. This chapter summarizes some of the problems that your team might encounter and provides advice and strategies for handling these problems at the outset.

Unfortunately, many problems that arise in student teams are never addressed — or are mentioned only at the end of the project, when it may be too late. To help you address problems early, this chapter provides many examples of how you can phrase uncomfortable requests to teammates and some example e-mails you might use.

Problems with Showing Up and Turning in Work

As the final deadline for his project approaches, Chad writes about the problems his group is experiencing:

Jessica and Dave have not both shown up to class on the same day, much less on time, within the last two weeks. I am beginning to feel like a babysitter. I also feel like the weight of work has shifted onto me. Our presentation is only five days away. Dave is trying to work on a new survey, but this time for professors. Jessica doesn’t have a freakin’ clue what is going on. This has not been a fun week.

Resa expresses a slightly different problem at the end of her project:

My biggest complaint is with Gene. All of the reprocessed information that he brought to class was not usable. I think I spent more time making his contributions fit than he spent doing it the first time. I tried to get his input, but it took so long to get responses out of him and then they were worthless. . . . I really do feel that the project they are taking credit for is about 90 percent mine.

Teams should never allow problems to go on as long as Chad and Resa did. Creating a clear task schedule and having an effective project manager are the best ways to prevent the problems they experienced; nonetheless, even with these in place, you may still have problems with “slacker” (or just incompetent) teammates. This chapter presents some strategies you can use to handle specific problems with teammates who slack off.

PROBLEM:

A teammate misses a meeting

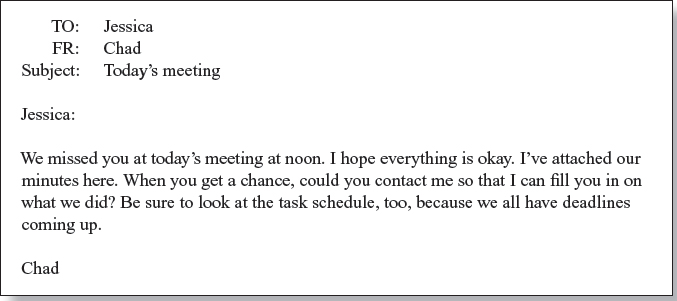

Everybody has emergencies or illnesses (or forgetfulness) that may result in missing a meeting. If any team members miss a meeting, they should contact the project manager as soon as possible to explain their absence and to ask what they missed. If they don’t contact the team, the project manager can send a friendly reminder (see Figure 8.1).

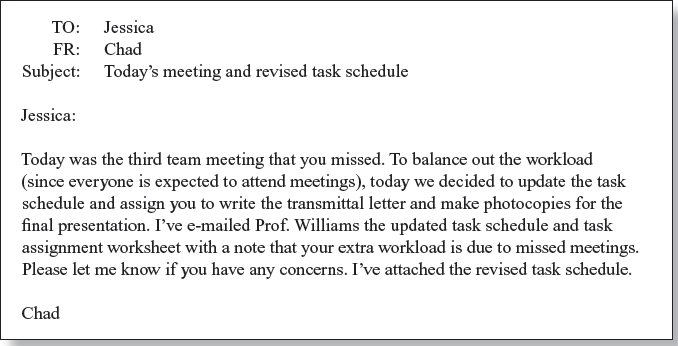

If a team member routinely misses meetings, you need to take some action, such as assigning this person some extra work (see Figure 8.2). For instance, you might assign him or her a clerical task that others don’t want to do. However, don’t use this tactic if the team member has also missed deadlines — assigning additional work to a person who has proved to be untrustworthy may put the group even further behind. The following section outlines how to proceed if a team member misses deadlines.

PROBLEM:

A teammate misses a deadline

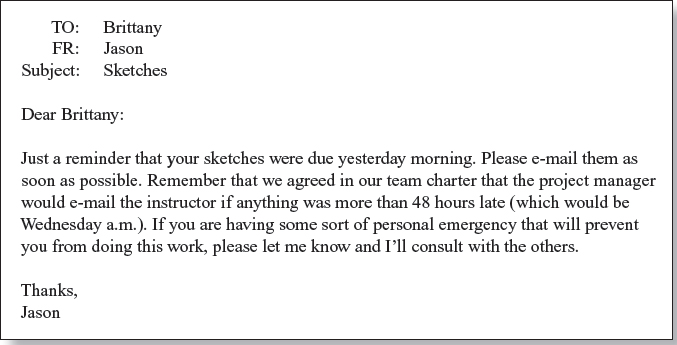

Failure to meet deadlines — a common problem for teams — is often caused by a team’s failure to maintain an up-to-date task schedule. As you learned in Chapter 4, “Getting Started with the Task Schedule,” the most important thing you can do to ensure that a team project runs smoothly is to maintain and publicize the task schedule. However, even with a task schedule, team members will sometimes miss deadlines — they might forget about due dates, or run into personal problems, or find that the work took longer than they anticipated. A gentle reminder is appropriate in these cases. In Figure 8.3, note how the presence of a team charter makes Jason’s task easier — he simply has to remind his teammate of the consequences that everyone (including Brittany) agreed on at the beginning of the project.

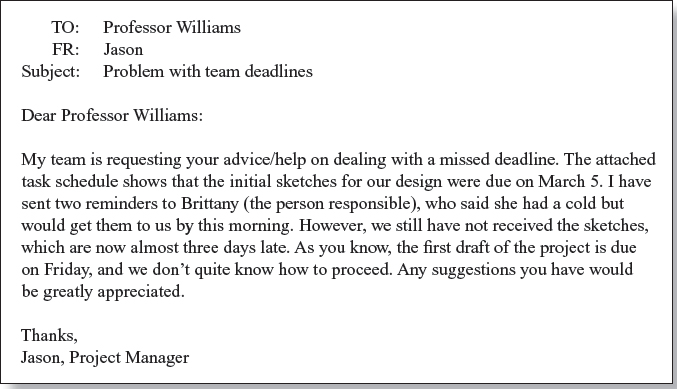

The team charter should specify how long the team should wait before enforcing the consequences of a missed deadline. If at the end of this time period the team member still has not turned in his or her work (or has turned in very incomplete work), you should notify the instructor. When you do so, you don’t have to point fingers; instead, just describe the situation as objectively as possible (see Figure 8.4).

Students often feel that informing the instructor of problems is “tattling” on their teammates. However, you need to think ahead to the workplace, where a team that doesn’t report problems to a supervisor will face severe reprimands. Your note to the instructor doesn’t need to be accusatory — simply state the facts. Your instructor may respond by sending a strong reminder, removing the offending person from the team and giving the team a new charge or new deadlines, or reducing the offending person’s contribution grade.

Some situations may warrant special consideration. For example, a teammate may have a serious medical or personal emergency that prevents him or her from doing the work. In these exceptional cases, the project manager may want to consult with the rest of the team, suggesting a way to revise the task schedule so that another team member takes over this person’s deadline — with the understanding that the incapacitated team member will do additional work at the end of the project. Before you do this, however, make sure that the excuse is valid: you don’t want to assign an untrustworthy team member too much work at the end of the project, when it can be difficult for the team to recover.

PROBLEM:

A teammate turns in incomplete work

Sometimes, a teammate will meet a deadline but will turn in work that is substantially incomplete. To prevent this problem, the project manager should immediately skim all work that is turned in to ensure that all the required parts are included. If anything is missing, the project manager should immediately e-mail the team member, specifying which parts are missing and giving him or her a deadline for turning in a complete draft. If a complete version is not turned in by the deadline, the project manager should notify the instructor. The next section contains sample e-mails for dealing with this situation.

PROBLEM:

A teammate turns in poor-quality work

This problem is a little more difficult to handle than the previous two because the difference between an acceptable and an unacceptable draft is often a gray area that requires a judgment call.

When a team member turns in work that the project manager feels is substantially below the group’s quality standards, the project manager should contact the other team members privately and ask if anyone else agrees with this assessment. If at least one other person agrees that the team can’t use the work, the project manager should e-mail the teammate who turned in the work and ask for a revision. Figure 8.5 illustrates a request for a revised draft. The request for revision should

- briefly explain why the work was considered substandard or unusable

- provide specific suggestions about resources that the teammate can consult for help

- include a specific deadline for turning in the revised work

- ask the teammate to let the project manager know immediately if he or she will not be able to make the deadline or meet the requests

PROBLEM:

A teammate disappears completely

The sooner you take action when a teammate seems to have disappeared, the less likely it is that this situation will turn into a serious problem. If you believe that someone in your group has dropped out of the picture entirely, you should notify your instructor (see Figure 8.6).

Problems with Personal Interactions

Midway through his project, Brian expresses some concerns about his teammates:

Things are not going well on our team. I have heard Daniel talk about how he could be writing things so much better than Bethany and about how she is just “getting the job done.” Daniel doesn’t seem to trust anybody except himself. Bethany is not completely innocent either. If you listen, you’ll notice that she basically shoots down most of his ideas or makes fun of them.

Jessica has more pointed things to say about one of her teammates:

I just didn’t, I didn’t think that my judgment was respected by Josh at all. He never listened to anything I had to say. I didn’t think that he saw me as a person in the group. He saw me as a, a female or something. . . . And I just cannot cope with somebody like that.

Teams often have problems with interpersonal conflict because teammates just don’t seem to get along. This section provides advice for handling situations in which low trust or high resentment is interfering with group progress.

PROBLEM:

My team doesn’t trust me to do good work

Teammates may have a number of reasons for not trusting one another to do good work. Sometimes, team members may behave in ways that make others question their competence. At other times, team members may have prejudices against certain groups or particular people. Before you assume that your team is prejudiced against you, make sure that you are not engaging in some behavior that makes them question whether you are capable of doing good work.

The following list describes behaviors that can make your team lose trust in you and provides some ways to regain respect within your team:

Are you failing to submit quality work on time? If you miss a deadline or turn in poor-quality work, your teammates may distrust your ability to do good work: you have already let them down once, and they have reason to worry that you may do it again. If your team has lost trust in you, you need to work extra hard to regain that trust. Some ways to regain trust are:

- Turn work in early.

- Ask questions. You may think that asking questions would make teammates worry about your competence, but it can often have the opposite effect. When you ask questions, your teammates know that you are working on the problem; if you are asking relevant questions, they know that you are on the right track and will likely meet deadlines. You should never turn in work late because you are unsure about what to do. This will ensure that your work not only is late but also may be of poor quality: the worst of both worlds. Instead, ask questions early so that you can get the help you need. If you are uncomfortable asking your team for help, make an appointment with your instructor for individual help on the task (this is what instructors are for) or seek an on-campus tutoring resource. Many schools have writing centers, where you can meet with a tutor to go over writing problems, and computer resource centers, where you can go for assistance on technical matters. In fact, many writing centers can also provide advice on preparing Web sites, PowerPoint presentations, or multimodal projects — ask when you call for an appointment.

Are you being self-deprecating or talking too much about your shortcomings? If you are always talking about how little you know, your lack of skills, how you struggle with grades, your incompetence with computers, or how smart others are in comparison to you, your teammates may believe this talk and be hesitant to trust you with major work. This is particularly the case in masculine environments in which self-promotion may be part of the culture. (See Chapter 7, “Communication Styles and Team Diversity,” for more on the problems of both self-promoting and self-deprecating speech.) You don’t have to talk about how great you are, but nor should you advertise your shortcomings. If you realize that your teammates have come to distrust you because you have been self-deprecating, you can:

- Explain that you often sell yourself short and ask for more work. Let your teammates know that even though you sometimes belittle your abilities, you still want to be challenged. Ask to be assigned additional or more challenging tasks, and offer to complete the work early so that the team doesn’t have to worry about being stuck with low-quality work.

Do you appear confused or disengaged in team meetings? Take a look at Team Video 2: Shelly, Will, and Ben. When Ben viewed this video in his final team meeting, he was shocked to see how disengaged he was from the group. He said that he gave the appearance that he didn’t care about the project. Judging from this behavior, Ben’s teammates would have been justified in wondering whether they could trust him. If you are worried that you may be giving the wrong impression during team meetings, you can:

- Review the task schedule and read your e-mail before the meeting. Make sure that you know what the team is doing before you go to the meeting.

- Start the meeting by saying something. Show the team that you have something to say by speaking early. Ask a question or make a comment about the task schedule or about a recent e-mail that was sent. If someone has asked for feedback on a draft, make sure that you have something to say (see Chapter 6, “Revising with Others”).

- Sit forward, look up, and make eye contact. Use body language to show that you are engaged.

Sometimes, however, your teammates may be prejudiced against you for no reason. If you believe that your teammates are reluctant to assign you challenging work because their prejudice makes them distrust your ability to do high-quality work, you can confront this distrust proactively by saying, “You don’t seem to have confidence in me. I would like to take on task X. I can do it before the deadline so that I have plenty of time to redo it if the team is unhappy,” or “I would like to take on task X. I promise to check with the teaching assistant [or run it past the instructor, or go to the writing center] before turning it in to the team.” Such an approach lets your teammates know that you sense their prejudice but are going to turn in high-quality work anyway.

PROBLEM:

My team isn’t listening to me — or is taking a direction I disagree with

Even if your teammates trust you to do good work, you may occasionally have trouble getting your ideas on the table. When team discussions are competitive, speakers with a considerate speaking norm often have difficulty making themselves heard (see Chapter 7, “Communication Styles and Team Diversity”).

If you have difficulty getting your teammates to listen to you, try the following strategies:

Learn how to enter competitive conversations. To increase the likelihood that your team will listen to you in face-to-face meetings, try the following strategies:

- Speak up early in meetings. Be one of the first people to speak so that your teammates will get used to thinking of you as someone who has something to contribute.

- Show that you are prepared. Before the meeting, read all relevant information, check your e-mail, and become familiar with the task schedule. Begin the meeting by saying that you have reviewed all the materials and have some suggestions.

- Develop strategies for dealing with interruptions. If you get cut off when you start to speak, hold up your hand like a stop sign or say “Just a minute, I’m not done yet.” (See Chapter 7, “Communication Styles and Team Diversity,” for more strategies for dealing with interruptions.)

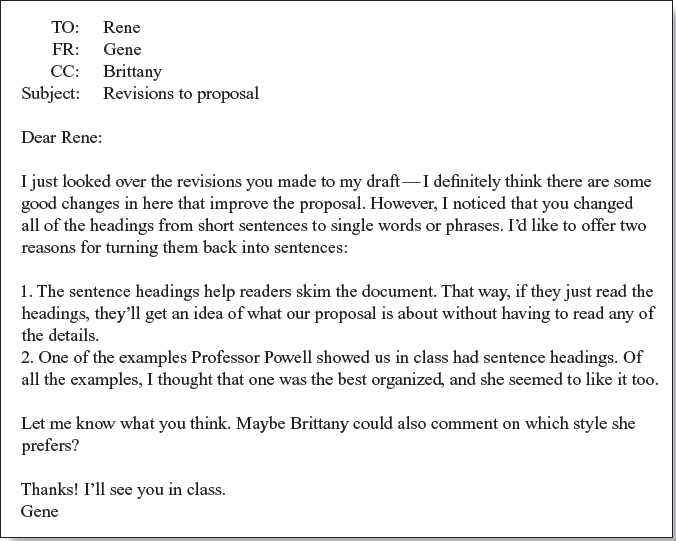

Move the conversation to writing. If you are not an assertive speaker, you might have greater success making yourself heard in writing than in a face-to-face conversation. You can’t get interrupted in an e-mail. Moreover, e-mailing your thoughts gives you a chance to state your ideas without the pressure and competition of a face-to-face meeting. You may want to begin the next meeting by reminding teammates of your e-mail and summarizing your main points. Figure 8.7 illustrates how a team member moves the conversation to writing.

Prepare an alternate draft. Because it can be time-consuming, this strategy is probably a last resort. However, if you strongly disagree with what your team is doing, you can prepare another draft (or partial draft) of the document and ask an objective outsider (such as your instructor) to comment on both versions. Don’t tell this person which draft is yours. Also, keep your request neutral: simply ask this person to comment on which draft he or she feels is better. Figure 8.8 illustrates this strategy.

PROBLEM:

Other team members are not committed to a high-quality product

Sometimes, your teammates may not be committed to producing high-quality work. However, if your group has prepared a team charter, you may be able to persuade your teammates to make changes by appealing to the goals and criteria the team agreed on at the start of the project. Base your request for changes closely on the language used in the team charter.

If the team still seems unmotivated to do high-quality work, you might ask your instructor or another knowledgeable outsider to comment on the work done so far. These comments may motivate team members to increase their efforts on the project. Or you might ask your instructor to share his or her grading rubric (a list of the criteria with which the project will be evaluated). Using this rubric, go over the project and point out specific areas where you think the team is failing to meet expectations.

PROBLEM:

My teammates do and say things I find disturbing or demeaning

Some situations are simply intolerable. If, for instance, a team member makes sexist or racist comments, you should report these to your instructor or (if you feel uncomfortable talking to the instructor) to an adviser or a faculty member of a group such as the Society for Women Engineers. These authority figures can advise you on how to handle the situation. Comments do not need to be directed to anyone in the group (or anyone in particular) to be offensive. Even generalized comments about sex or race can make teamwork uncomfortable — even when they’re not meant to be taken personally.

If a teammate makes romantic advances or personal comments, you can tell the project manager privately that you feel uncomfortable with this person; you can also request that the task schedule be changed to limit your contact. It is inappropriate for someone to ask a teammate out on a date while the project is ongoing — such personal issues should wait until the project is finished. If the person making you uncomfortable is the project manager, talk to the instructor or ask another team member to intervene on your behalf. Keep in mind that in the workplace, such behavior can lead to harassment suits or worse; therefore, students need to learn what is inappropriate while they are still in school.

Other problems may be more difficult to resolve, especially when it is hard to determine whether a teammate’s comments and behavior are based on prejudice, personal dislike, or some other factor. If no outright sexist or racist behavior or harassment is going on, try to resolve the problem through other strategies. To find strategies that might improve your situation, review the sections on how to deal with lack of trust or failure to listen or some of the following sections on revision.

PROBLEM:

My teammates criticize my work excessively

Sometimes, team members may be excessively harsh on someone else on the team in order to avoid work or to keep their own work out of the spotlight. If this appears to be the case, talk to the project manager about updating the task schedule and rebalancing the workload. If you feel that your teammates are using criticism to try to get you to do what should be their work, you might suggest that they be responsible for making revisions.

However, before you take any action, be sure that you are not responding defensively to justifiable and productive criticism. Allow yourself a cooling-off period (24 hours if possible) before taking any action. Then return to the criticism to see whether it is justified. Perhaps your teammate has pointed out a legitimate problem but has suggested an incorrect solution — or has misidentified the problem. Take a critical look at your writing and see if something needs to be changed, even if it’s not exactly what your teammate pointed out. If, ultimately, you feel that a teammate is treating you unfairly, ask someone else on the team whether he or she has also noted this behavior. This person may be able to help you find a solution.

Problems with Revision

Erin describes in her final interview how a teammate resisted any revisions that other team members wanted to implement:

Well, Jin did the first draft of the Web site, and she said we could revise it, but then anytime we wanted to do something different, it was “No, don’t do that, you can’t do that,” that sort of thing. And I remember it was funny because initially she told a story about how when she was in preschool, a little boy was sitting next to her coloring a picture, and she grabbed the picture from him and said, “I’ll do it for you. It will be better this way.” She told that story, and it kind of fit into the project.

Ben, meanwhile, had the opposite problem with his team:

And I was disappointed. I thought we’d get a chance to improve, but everybody was just like “yeah, yeah, that’s good.” So there was no motivation to revise.

Teams often run into conflict when they get into the nitty-gritty details of making revisions. This section describes strategies for handling those who either don’t want to listen to their teammates’ suggestions for revisions or don’t feel comfortable suggesting revisions to their peers’ work.

PROBLEM:

Team members are not open to revisions to their work — or team members ignore the suggestions I make for revision

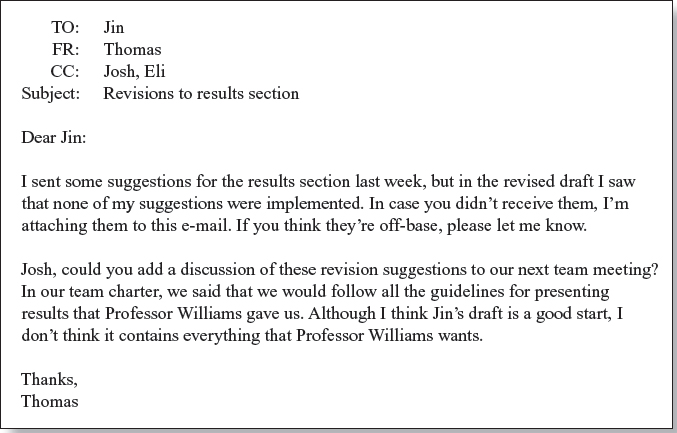

Sometimes, you may suggest revisions to material that a teammate has prepared, only to have these suggestions ignored or dismissed. If a teammate ignores your suggestions or just acts as if your feedback doesn’t exist, first you need to find out why your suggestions were ignored. A teammate might ignore your suggestions because he or she (1) agrees that the suggestions would improve the work but doesn’t feel that they are worth the time or effort to implement, (2) disagrees with the suggestions, or (3) overlooked, missed, or forgot about the suggestions. If you want to find out which of these three reasons applies, send a simple “reminder” e-mail to your teammate (see Figure 8.9), with a copy to other team members if necessary.

If your teammate agrees with the suggestions but doesn’t want to implement them, ask the team to discuss whether the suggestions are worth implementing. To make sure that the ideas are discussed, ask the project manager to put this item on the agenda for a future meeting, or ask team members to comment on your suggestions via e-mail. If the changes will be time-consuming, the team may need to consider updating the task schedule and redistributing the workload.

If your team agrees with your suggested revisions but decides that they are not worth the time to implement, you may need to take on additional work to ensure that the project is done right. However, make sure that the project manager updates the task schedule to show the extra work you have done.

If the team disagrees with your suggestions and you feel they are worth pursuing, refer to the section “My team isn’t listening to me — or is taking a direction I disagree with.” In this situation, you might want to create an alternate draft and ask the instructor or someone else to make a judgment call (see Figure 8.8).

PROBLEM:

My team is destroying my work

Occasionally, you may hand off a document to a teammate, only to have that person make radical revisions that you disagree with. In this situation, using Track Changes or another software tool that keeps a history of revisions can be quite useful because everyone can go back and recover material that may have been lost during another person’s revisions (see Chapter 6, “Revising with Others”).

If you feel that your teammates’ revisions weaken rather than improve your work, state the reasons for your position and ask the team to reconsider (see Figure 8.10).

You should always feel free to ask teammates to reconsider revisions they have made to your work, but sometimes you need to accede to the group and follow the team’s decision. To be sure that you are not just being defensive about your own work, wait 24 hours before responding to the revisions. Then, before you respond, read the revisions again and see whether they do in fact improve the document.

If the team reaches an impasse and cannot agree on revisions to a document, a good strategy is to ask an outsider (such as an instructor or another member of the class) to look over the different versions and comment on which version he or she prefers. The team should agree in advance to abide by that person’s decision.

PROBLEM:

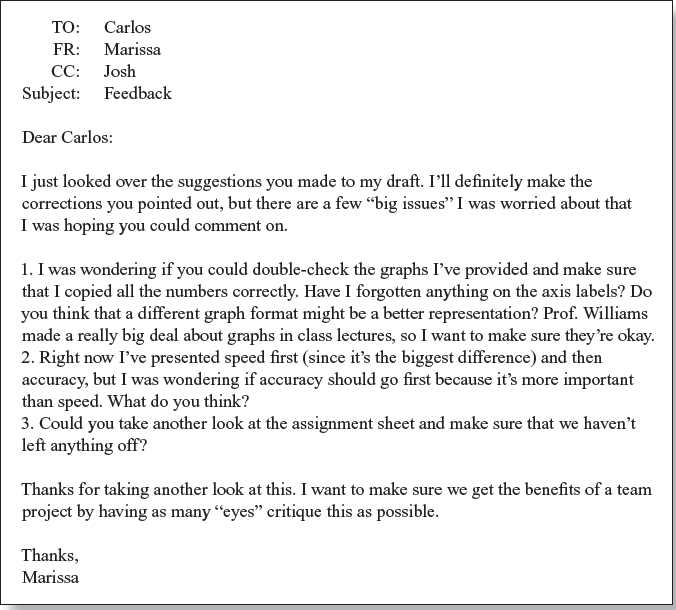

Team members are not giving adequate feedback

If a teammate has been assigned to provide suggestions on (or make revisions to) your work and simply corrects a few typos or says that it “looks good,” you need to encourage your teammate to give more thorough feedback. In such cases, you can try to obtain feedback by asking some specific questions, as shown in Figure 8.11.

Even with a reminder and another invitation to provide feedback, some teammates may neglect this duty. If so, you may want to contact the project manager and ask that another teammate (or the project manager) be assigned to read and comment on the draft. Make sure that the task schedule gets updated so that this person receives credit for the additional work he or she has done.

PROBLEM:

I’m not sure how to give good feedback to team members

Giving feedback to others can be unnerving — especially if you are worried that your writing skills may not be as good as theirs. Using Track Changes or another software tool that records a history of revisions can be very useful because your teammates can easily go back and recover the original document if they disagree with your revisions (see Chapter 6, “Revising with Others”).

Even if you are unsure of your writing abilities, you can take a few steps to ensure that you give good-quality feedback:

- Read the assignment sheet and note everything that needs to appear in your document. Then review the document carefully and make sure that nothing has been left out.

- Try to obtain a copy of the grading rubric (a sheet that lists the evaluation criteria) that your instructor will be using to evaluate the project, and note any areas where you think the project might be lacking. Even if you are not sure how to fix these deficiencies, simply pointing them out might prod other team members to think of ways to improve the document.

- Visit your campus writing center and ask a tutor to help you find things to critique. Bring a copy of the assignment instructions (and grading rubric if you have one) so that the tutor can get a general idea of what your instructor expects. Even if the tutor doesn’t know all the specifics of the assignment, he or she should be able to point out some weak aspects of your document and to note general writing issues such as poor grammar, inconsistent logic, or poor organization.