Before skimming the following essay, apply the previewing techniques discussed above, and complete the Thinking Critically: Previewing activity on Paraphrase, Patchwriting, and Plagiarism.

SANJAY GUPTA

Dr. Sanjay Gupta (b. 1969) is a neurosurgeon and multiple Emmy award–winning television personality. As a leading public health expert, he has appeared widely on television, including the Oprah Winfrey Show, the Late Show with David Letterman, the Jon Stewart Show, and 60 Minutes. He is most well known as CNN’s chief medical correspondent. In 2011, Forbes magazine named him one of the ten most influential celebrities in America. The essay reprinted below originally appeared on CNN.com in August 2013.

Why I Changed My Mind on Weed

Over the last year, I have been working on a new documentary called “Weed.” The title “Weed” may sound cavalier, but the content is not.

I traveled around the world to interview medical leaders, experts, growers and patients. I spoke candidly to them, asking tough questions. What I found was stunning.

Long before I began this project, I had steadily reviewed the scientific literature on medical marijuana from the United States and thought it was fairly unimpressive. Reading these papers five years ago, it was hard to make a case for medicinal marijuana. I even wrote about this in a Time magazine article, back in 2009, titled “Why I Would Vote No on Pot.”

Well, I am here to apologize.

5 I apologize because I didn’t look hard enough, until now. I didn’t look far enough. I didn’t review papers from smaller labs in other countries doing some remarkable research, and I was too dismissive of the loud chorus of legitimate patients whose symptoms improved on cannabis.

Instead, I lumped them with the high-visibility malingerers, just looking to get high. I mistakenly believed the Drug Enforcement Agency listed marijuana as a Schedule 1 substance because of sound scientific proof. Surely, they must have quality reasoning as to why marijuana is in the category of the most dangerous drugs that have “no accepted medicinal use and a high potential for abuse.”

They didn’t have the science to support that claim, and I now know that when it comes to marijuana neither of those things are true. It doesn’t have a high potential for abuse, and there are very legitimate medical applications. In fact, sometimes marijuana is the only thing that works. Take the case of Charlotte Figi, whom I met in Colorado. She started having seizures soon after birth. By age 3, she was having 300 a week, despite being on 7 different medications. Medical marijuana has calmed her brain, limiting her seizures to 2 or 3 per month.

I have seen more patients like Charlotte first hand, spent time with them and come to the realization that it is irresponsible not to provide the best care we can as a medical community, care that could involve marijuana.

We have been terribly and systematically misled for nearly 70 years in the United States, and I apologize for my own role in that.

10 I hope this article and upcoming documentary will help set the record straight.

On August 14, 1970, the Assistant Secretary of Health, Dr. Roger O. Egeberg, wrote a letter recommending the plant, marijuana, be classified as a Schedule 1 substance, and it has remained that way for nearly 45 years. My research started with a careful reading of that decades-old letter. What I found was unsettling. Egeberg had carefully chosen his words:

“Since there is still a considerable void in our knowledge of the plant and effects of the active drug contained in it, our recommendation is that marijuana be retained within Schedule 1 at least until the completion of certain studies now under way to resolve the issue.”

Not because of sound science, but because of its absence, marijuana was classified as a Schedule 1 substance. Again, the year was 1970. Egeberg mentions studies that are under way, but many were never completed. As my investigation continued, however, I realized Egeberg did in fact have important research already available to him, some of it from more than 25 years earlier.

HIGH RISK OF ABUSE

In 1944, New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia commissioned research to be performed by the New York Academy of Science. Among their conclusions: they found marijuana did not lead to significant addiction in the medical sense of the word. They also did not find any evidence marijuana led to morphine, heroin or cocaine addiction.

15 We now know that while estimates vary, marijuana leads to dependence in around 9 to 10% of its adult users. By comparison, cocaine, a Schedule 2 substance “with less abuse potential than Schedule 1 drugs,” hooks 20% of those who use it. Around 25% of heroin users become addicted.

The worst is tobacco, where the number is closer to 30% of smokers, many of whom go on to die because of their addiction.

There is clear evidence that in some people marijuana use can lead to withdrawal symptoms, including insomnia, anxiety and nausea. Even considering this, it is hard to make a case that it has a high potential for abuse. The physical symptoms of marijuana addiction are nothing like those of the other drugs I’ve mentioned. I have seen the withdrawal from alcohol, and it can be life threatening.

I do want to mention a concern that I think about as a father. Young, developing brains are likely more susceptible to harm from marijuana than adult brains. Some recent studies suggest that regular use in teenage years leads to a permanent decrease in IQ. Other research hints at a possible heightened risk of developing psychosis.

Much in the same way I wouldn’t let my own children drink alcohol, I wouldn’t permit marijuana until they are adults. If they are adamant about trying marijuana, I will urge them to wait until they’re in their mid-20s, when their brains are fully developed.

MEDICAL BENEFIT

20 While investigating, I realized something else quite important. Medical marijuana is not new, and the medical community has been writing about it for a long time. There were in fact hundreds of journal articles, mostly documenting the benefits. Most of those papers, however, were written between the years 1840 and 1930. The papers described the use of medical marijuana to treat “neuralgia, convulsive disorders, emaciation,” among other things.

A search through the U.S. National Library of Medicine this past year pulled up nearly 20,000 more recent papers. But the majority were research into the harm of marijuana, such as “Bad trip due to anticholinergic effect of cannabis,” or “Cannabis induced pancreatitis” and “Marijuana use and risk of lung cancer.”

In my quick running of the numbers, I calculated about 6% of the current U.S. marijuana studies investigate the benefits of medical marijuana. The rest are designed to investigate harm. That imbalance paints a highly distorted picture.

THE CHALLENGES OF MARIJUANA RESEARCH

To do studies on marijuana in the United States today, you need two important things.

First of all, you need marijuana. And marijuana is illegal. You see the problem. Scientists can get research marijuana from a special farm in Mississippi, which is astonishingly located in the middle of the Ole Miss campus, but it is challenging. When I visited this year, there was no marijuana being grown.

25 The second thing you need is approval, and the scientists I interviewed kept reminding me how tedious that can be. While a cancer study may first be evaluated by the National Cancer Institute, or a pain study may go through the National Institute for Neurological Disorders, there is one more approval required for marijuana: NIDA, the National Institute on Drug Abuse. It is an organization that has a core mission of studying drug abuse, as opposed to benefit.

Stuck in the middle are the legitimate patients who depend on marijuana as a medicine, oftentimes as their only good option.

Keep in mind that up until 1943, marijuana was part of the United States drug pharmacopeia. One of the conditions for which it was prescribed was neuropathic pain. It is a miserable pain that’s tough to treat. My own patients have described it as “lancinating, burning and a barrage of pins and needles.” While marijuana has long been documented to be effective for this awful pain, the most common medications prescribed today come from the poppy plant, including morphine, oxycodone and dilaudid.

Here is the problem. Most of these medications don’t work very well for this kind of pain, and tolerance is a real problem.

Most frightening to me is that someone dies in the United States every 19 minutes from a prescription drug overdose, mostly accidental. Every 19 minutes. It is a horrifying statistic. As much as I searched, I could not find a documented case of death from marijuana overdose.

30 It is perhaps no surprise then that 76% of physicians recently surveyed said they would approve the use of marijuana to help ease a woman’s pain from breast cancer.

When marijuana became a Schedule 1 substance, there was a request to fill a “void in our knowledge.” In the United States, that has been challenging because of the infrastructure surrounding the study of an illegal substance, with a drug abuse organization at the heart of the approval process. And yet, despite the hurdles, we have made considerable progress that continues today.

Looking forward, I am especially intrigued by studies like those in Spain and Israel looking at the anti-cancer effects of marijuana and its components. I’m intrigued by the neuro-protective study by Lev Meschoulam in Israel, and research in Israel and the United States on whether the drug might help alleviate symptoms of PTSD. I promise to do my part to help, genuinely and honestly, fill the remaining void in our knowledge.

Citizens in 20 states and the District of Columbia have now voted to approve marijuana for medical applications, and more states will be making that choice soon. As for Dr. Roger Egeberg, who wrote that letter in 1970, he passed away 16 years ago.

I wonder what he would think if he were alive today.

THINKING CRITICALLY Previewing

Provide the missing information for Sanjay Gupta and his essay “Why I Changed My Mind on Weed.”

| PREVIEWING STRATEGIES | TYPES OF QUESTIONS | ANSWERS |

| Author | Who is he? What expertise does he have? What credibility does he have? How difficult is the writing likely to be? | |

| Title | What does the title reveal about the essay’s content? Does it give any clues about how the argument will take shape? | |

| Place of Publication | How does the place of publication help you understand the argument? What type of audiences will it be likely to target? | |

| Context | By placing the article in the context of its time — given trends in the conversations about or popular understandings of the subject — what can you expect about the author’s position? | |

| Skimming | As you skim over the first several paragraphs, where do you first realize the purpose of the essay? What is Gupta’s argument? What major forms of evidence does he offer? |

To complete this activity online, click here.

To complete this activity online, click here.

THE “FIRST AND LAST” RULE As noted above, authors often place main points of emphasis at the beginnings and endings of essays. They also place important material at the beginnings and endings of paragraphs and sentences.

When writing, you can emphasize main points by using the first and last rule. Don’t bury your most important material in the middle of sentences, paragraphs, or entire papers. Make it stand out.

Consider the following observations. Select two that you find to be most important.

Gupta is one of the most respected voices in public health.

Gupta argues for the legalization of medical marijuana.

Gupta’s article was written for CNN News in 2011.

Gupta rejects his previous position on medical marijuana and apologizes for his oversight.

The article was important because it represented a shift in approach by a leading doctor.

Now arrange these statements in a short paragraph, using the first and last rule to emphasize the two that you selected as most important. Compare your paragraph to your classmates’ paragraphs. How do they compare?

READING WITH A CAREFUL EYE: UNDERLINING, HIGHLIGHTING, ANNOTATING

Once you have a general idea of the work — not only an idea of its topic and thesis but also a sense of the way in which the thesis is argued — you can go back and start reading it carefully.

As you read, underline or highlight key passages, and make annotations in the margins. Because you’re reading actively, or interacting with the text, you won’t simply let your eye rove across the page.

Highlight what seem to be the chief points, so that later when reviewing the essay you can easily locate the main passages.

But don’t overdo a good thing. If you find yourself highlighting most of a page, you’re probably not thinking carefully enough about what the key points are.

Similarly, your marginal annotations should be brief and selective. They will probably consist of hints or clues, comments like “doesn’t follow,” “good,” “compare with Jones,” “check this,” and “really?”

In short, in a paragraph you might highlight a key definition, and in the margin you might write “good,” or “in contrast,” or “?” if you think the definition is unclear or incorrect.

With many electronic formats, you can use tools to highlight or annotate. Also consider copying and pasting passages that you would normally highlight in a Google document. Include a link to the piece, and create an RSS feed to the journal’s Web site. Having your notes in an electronic format makes it easy to access and use them later.

In all these ways, you interact with the text and lay the groundwork for eventually writing your own essay on what you have read.

What you annotate will depend largely on your purpose. If you’re reading an essay in order to see how the writer organizes an argument, you’ll annotate one sort of thing. If you’re reading in order to challenge the thesis, you’ll annotate other things. Here is a passage from an essay entitled “On Racist Speech,” with a student’s rather skeptical, even aggressive, annotations. But notice that the student apparently made at least one of the annotations — “Definition of ‘fighting words’” — chiefly in order to remind herself to locate where the definition of an important term appears in the essay. The essay, printed in full on Charles R. Lawrence III, On Racist Speech, is by Charles R. Lawrence III, a professor of law at Georgetown University. It originally appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education (October 25, 1989), a publication read chiefly by college and university faculty members and administrators.

Example of such a policy?

|

University officials who have formulated policies to respond to incidents of racial harassment have been characterized in the press as “thought police,” but such policies generally do nothing more than impose sanctions against intentional face-to-face insults. When racist speech takes the form of face-to-face insults, catcalls, or other assaultive speech aimed at an individual or small group of persons, it falls directly within the “fighting words” exception to First Amendment protection. The Supreme Court has held that words “which ‘by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace’” are not protected by the First Amendment. If the purpose of the First Amendment is to foster the greatest amount of speech, racial insults disserve that purpose. Assaultive racist speech functions as a preemptive strike. The invective is experienced as a blow, not as a proffered idea, and once the blow is struck, it is unlikely that a dialogue will follow. Racial insults are particularly undeserving of First Amendment protection because the perpetrator’s intention is not to discover truth or initiate dialogue but to injure the victim. In most situations, members of minority groups realize that they are likely to lose if they respond to epithets by fighting and are forced to remain silent and submissive. |

“THIS; THEREFORE, THAT”

To arrive at a coherent thought or series of thoughts that will lead to a reasonable conclusion, a writer has to go through a good deal of preliminary effort. When we discussed heuristics in Generating Ideas: Writing as a Way of Thinking, we talked about patterns of thought that stimulate initial ideas. The path to sound conclusions involves similar thought patterns that carry forward the arguments presented in the essay:

While these arguments are convincing, they fail to consider …

While these arguments are convincing, they must also consider …

These arguments, rather than being convincing, instead prove …

While these authors agree, in my opinion …

Although it is often true that …

Consider also …

What sort of audience would agree with such an argument?

What sort of audience would be opposed?

What are the differences in values between these two kinds of audiences?

All of these patterns can serve as heuristics or prompts — that is, they can stimulate the creation of ideas.

Moreover, for the writer to convince the reader that the conclusion is sound, the reasoning behind the conclusion must be set forth in detail, with a good deal of “This; therefore, that”; “If this, then that”; and “Others might object at this point that….” The arguments in this book require more comment than President Calvin Coolidge supposedly provided when his wife, who hadn’t been able to attend church one Sunday, asked him what the preacher talked about in his sermon. “Sin,” Coolidge said. His wife persisted: “What did the preacher say about it?” Coolidge’s response: “He was against it.”

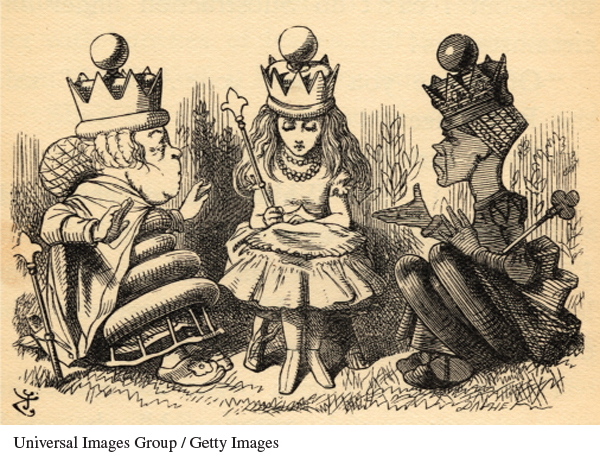

But, again, when we say that most of the arguments in this book are presented at length and require careful reading, we don’t mean that they are obscure; we mean, rather, that you have to approach the sentences thoughtfully, one by one. In this vein, recall an episode from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass:

“Can you do Addition?” the White Queen asked. “What’s one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one?”

“I don’t know,” said Alice. “I lost count.”

“She can’t do Addition,” the Red Queen said.

It’s easy enough to add one and one and one and so on, and of course Alice can do addition — but not at the pace that the White Queen sets. Fortunately, you can set your own pace in reading the cumulative thinking set forth in the essays we reprint in this book. Skimming won’t work, but slow reading — and thinking about what you’re reading — will.

When you first pick up an essay, you may indeed want to skim it, for some of the reasons mentioned on Generating Ideas: Writing as a Way of Thinking, but sooner or later you have to settle down to read it and think about it. The effort will be worthwhile. Consider what John Locke, a seventeenth-century English philosopher, said:

Reading furnishes the mind with materials of knowledge; it is thinking [that] makes what we read ours. We are of the ruminating kind, and it is not enough to cram ourselves with a great load of collections; unless we chew them over again they will not give us strength and nourishment.

Often students read an essay just once, supposing that to reread would be repetitious. But much can be gleaned from a second reading, as new details will likely emerge and new ideas will be generated. Roland Barthes, a twentieth-century philosopher, warned against accepting a first reading as final. Far from being repetitive, “[r]e-reading,” he wrote, “saves the text from repetition, multiplies it in its variety and plurality.” What may actually be repetitious is reading something only once and, thinking you have it pinned down, repeating it (in your writing) and thereby sticking to your first and only impression.

DEFINING TERMS AND CONCEPTS

Suppose you’re reading an argument about whether a certain set of images is pornography or art. For the present purpose, let’s use a famous example from 1992, when American photographer Sally Mann published Immediate Family, a controversial book featuring numerous images of her three children (then ages 12, 10, and 7) in various states of nakedness during their childhood on a rural Kentucky farm. Mann is considered a great photographer and artist (“America’s Best Photographer,” according to Time magazine in 2001), and Immediate Family is very well regarded in the art community (“one of the great photograph books of our time,” according to the New Republic). But some critics couldn’t separate the images of Mann’s own naked children from the label “child pornography.”

When reading, attend carefully to how terms and concepts are used for the purposes of advancing an argument. In this case, you might begin by asking, “What is pornography? What is art?” If writers and readers cannot agree on basic definitions of the terms and concepts that structure the debate, then argument is futile. And if an author doesn’t share your definition of a term or concept, then you might challenge the premise of his or her argument. If someone were to define pornography to include any images of nude children, that definition would include photographs taken for any reason — medical, sociological, anthropological, scientific — and would include even the innocent photographs taken by proud parents of their children swimming, bathing, and so on. It would also apply to some of the world’s great art. Most people do not seriously think the mere image of the naked body, adult or child, is pornography.

Pornography is often defined according to its intended effect on the viewer (“genital commotion,” Father Harold Gardiner, S.J., called it in Catholic Viewpoint on Censorship). In this definition, if images are eroticized (i.e., made erotic through style or symbolism), if they invite a sexual gaze, they are pornographic. This seems to be the definition that novelist Mary Gordon applied in a 1996 critique of Sally Mann:

Unless we believe it is ethically permissible for adults to have sex with children, we must question the ethics of an art which allows the adult who has the most power over these children — a parent, in this case a mother — to place them in a situation where they become the imagined sexual partner of adults…. It is inevitable that Sally Mann’s photographs arouse the sexual imaginations of strangers.

But is it enough to say something is pornographic if it “arouses the sexual imagination”? No, you might contend, because there is no way to predict what will arouse people’s sexual imaginations. Many kinds of images might arouse the sexual imaginations of different people. You might say in rebutting Gordon, “These are just pictures of children. Sure, they’re naked in some of them, but children have been symbols of purity and innocence in art since the dawn of civilization. If some people see these images as sexual, that’s their problem, not Mann’s.”

A RULE FOR WRITERS Be alert to how terms and concepts are defined both in your source material and in your own writing. Are your terms broadly, narrowly, or technically construed?

Writers often attempt to provide a provisional definition of important terms and concepts in their arguments. They may write, for example, “For the purposes of this argument, let’s define terrorism as X” (a broad definition) or “According to federal law, the term ‘international terrorism’ means A, B, and C” (a technical definition). If you do this and a reader wants to challenge your ideas, he must argue on your terms or else offer a different definition.

So that we are consistent with our own recommendations, allow us to define the difference between a “term” and a “concept.” A rule of thumb is that a term is more concrete and fixed than a concept. You may be able to find an authoritative source (like a federal law or an official policy) to help define a term. A concept is more open-ended and may have a generally agreed-upon definition, but rarely a strict or unchanging one. Concepts can be abstract but can also function powerfully in argumentation; love, justice, morality, psyche, health, freedom, bravery, obscenity, masculinity — these are all concepts. You may look up such words in the dictionary for general definitions, but the source won’t say much about how to apply the concepts.

Since you cannot assume that everyone has a shared understanding of concepts you may be using, it’s prudent for the purposes of effective writing to define them. You may find a useful definition of a concept given by an authoritative person, such as an expert in a field, as in “Stephen Hawking defines time as….” You might cite a respected authority, as in “Mahatma Gandhi defines love as….” Alternatively, you can combine several views and insert your own provisional definition. See “Thinking Critically: Defining Terms and Concepts” for an exercise.

THINKING CRITICALLY Defining Terms and Concepts

Examine each claim, and note the terms and concepts used. Provide a terminological (strict, codified by an authoritative source) or a conceptual (loose, self-generated) definition for each. What sources did you use? Compare your answers to those of your peers to see if they are similar or different.

| STATEMENT | DEFINITION | TYPE OF DEFINITION |

| Video games are addictive. | ||

| Poor people will suffer most from the new law. | ||

| The epidemic of obesity needs to be solved. | ||

| We must send troops to protect the national interest. | ||

| The Internet has ushered in a new age of progress. |

To complete this activity online, click here.

To complete this activity online, click here.