NORA EPHRON

Nora Ephron (1941–2012) attended Wellesley College and then worked as a reporter for the New York Post and as a columnist and senior editor for Esquire. Ephron wrote screenplays and directed films, including Sleepless in Seattle (1993), and continued to write essays on a wide variety of topics. “The Boston Photographs” is from her collection Scribble, Scribble: Notes on the Media (1978).

The Boston Photographs

“I made all kinds of pictures because I thought it would be a good rescue shot over the ladder . . . never dreamed it would be anything else. . . . I kept having to move around because of the light set. The sky was bright and they were in deep shadow. I was making pictures with a motor drive and he, the fire fighter, was reaching up and, I don’t know, everything started falling. I followed the girl down taking pictures. . . . I made three or four frames. I realized what was going on and I completely turned around, because I didn’t want to see her hit.”

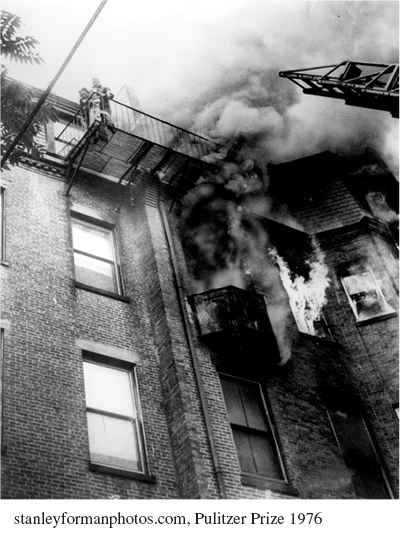

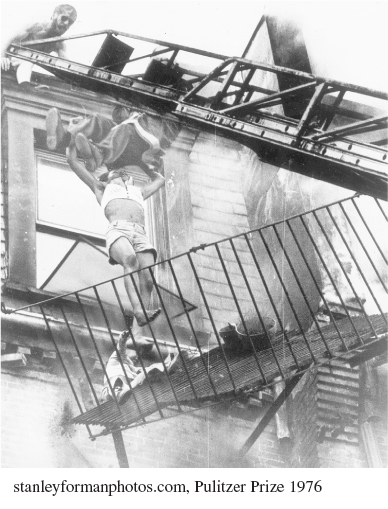

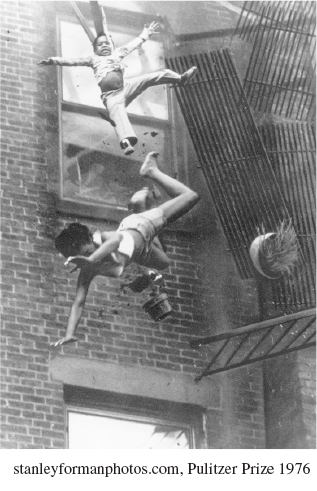

You probably saw the photographs. In most newspapers, there were three of them. The first showed some people on a fire escape — a fireman, a woman, and a child. The fireman had a nice strong jaw and looked very brave. The woman was holding the child. Smoke was pouring from the building behind them. A rescue ladder was approaching, just a few feet away, and the fireman had one arm around the woman and one arm reaching out toward the ladder. The second picture showed the fire escape slipping off the building. The child had fallen on the escape and seemed about to slide off the edge. The woman was grasping desperately at the legs of the fireman, who had managed to grab the ladder. The third picture showed the woman and child in midair, falling to the ground. Their arms and legs were outstretched, horribly distended. A potted plant was falling too. The caption said that the woman, Diana Bryant, nineteen, died in the fall. The child landed on the woman’s body and lived.

The pictures were taken by Stanley Forman, thirty, of the Boston Herald American. He used a motor-driven Nikon F set at 1/250, f5.6-S. Because of the motor, the camera can click off three frames a second. More than four hundred newspapers in the United States alone carried the photographs: The tear sheets from overseas are still coming in. The New York Times ran them on the first page of its second section; a paper in south Georgia gave them nineteen columns; the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post, and the Washington Star filled almost half their front pages, the Star under a somewhat redundant headline that read: SENSATIONAL PHOTOS OF RESCUE ATTEMPT THAT FAILED.

The photographs are indeed sensational. They are pictures of death in action, of that split second when luck runs out, and it is impossible to look at them without feeling their extraordinary impact and remembering, in an almost subconscious way, the morbid fantasy of falling, falling off a building, falling to one’s death. Beyond that, the pictures are classics, old-fashioned but perfect examples of photojournalism at its most spectacular. They’re throwbacks, really, fire pictures, 1930s tabloid shots; at the same time they’re technically superb and thoroughly modern — the sequence could not have been taken at all until the development of the motor-driven camera some sixteen years ago.

5 Most newspaper editors anticipate some reader reaction to photographs like Forman’s; even so, the response around the country was enormous, and almost all of it was negative. I have read hundreds of the letters that were printed in letters-to-the-editor sections, and they repeat the same points. “Invading the privacy of death.” “Cheap sensationalism.” “I thought I was reading the National Enquirer.” “Assigning the agony of a human being in terror of imminent death to the status of a side-show act.” “A tawdry way to sell newspapers.” The Seattle Times received sixty letters and calls; its managing editor even got a couple of them at home. A reader wrote the Philadelphia Inquirer: “Jaws and Towering Inferno are playing downtown; don’t take business away from people who pay good money to advertise in your own paper.” Another reader wrote the Chicago Sun-Times: “I shall try to hide my disappointment that Miss Bryant wasn’t wearing a skirt when she fell to her death. You could have had some award-winning photographs of her underpants as her skirt billowed over her head, you voyeurs.” Several newspaper editors wrote columns defending the pictures: Thomas Keevil of the Costa Mesa (California) Daily Pilot printed a ballot for readers to vote on whether they would have printed the pictures; Marshall L. Stone of Maine’s Bangor Daily News, which refused to print the famous assassination picture of the Vietcong prisoner in Saigon, claimed that the Boston pictures showed the dangers of fire escapes and raised questions about slumlords. (The burning building was a five-story brick apartment house on Marlborough Street in the Back Bay section of Boston.)

For the last five years, the Washington Post has employed various journalists as ombudsmen, whose job is to monitor the paper on behalf of the public. The Post’s current ombudsman is Charles Seib, former managing editor of the Washington Star; the day the Boston photographs appeared, the paper received over seventy calls in protest. As Seib later wrote in a column about the pictures, it was “the largest reaction to a published item that I have experienced in eight months as the Post’s ombudsman. . . .

“In the Post’s newsroom, on the other hand, I found no doubts, no second thoughts . . . the question was not whether they should be printed but how they should be displayed. When I talked to editors . . . they used words like ‘interesting’ and ‘riveting’ and ‘gripping’ to describe them. The pictures told of something about life in the ghetto, they said (although the neighborhood where the tragedy occurred is not a ghetto, I am told). They dramatized the need to check on the safety of fire escapes. They dramatically conveyed something that had happened, and that is the business we’re in. They were news. . . .

“Was publication of that [third] picture a bow to the same taste for the morbidly sensational that makes gold mines of disaster movies? Most papers will not print the picture of a dead body except in the most unusual circumstances. Does the fact that the final picture was taken a millisecond before the young woman died make a difference? Most papers will not print a picture of a bare female breast. Is that a more inappropriate subject for display than the picture of a human being’s last agonized instant of life?” Seib offered no answers to the questions he raised, but he went on to say that although as an editor he would probably have run the pictures, as a reader he was revolted by them.

In conclusion, Seib wrote: “Any editor who decided to print those pictures without giving at least a moment’s thought to what purpose they served and what their effect was likely to be on the reader should ask another question: Have I become so preoccupied with manufacturing a product according to professional traditions and standards that I have forgotten about the consumer, the reader?”

10 It should be clear that the phone calls and letters and Seib’s own reaction were occasioned by one factor alone: the death of the woman. Obviously, had she survived the fall, no one would have protested; the pictures would have had a completely different impact. Equally obviously, had the child died as well — or instead — Seib would undoubtedly have received ten times the phone calls he did. In each case, the pictures would have been exactly the same — only the captions, and thus the responses, would have been different.

But the questions Seib raises are worth discussing — though not exactly for the reasons he mentions. For it may be that the real lesson of the Boston photographs is not the danger that editors will be forgetful of reader reaction, but that they will continue to censor pictures of death precisely because of that reaction. The protests Seib fielded were really a variation on an old theme — and we saw plenty of it during the Nixon-Agnew years — the “Why doesn’t the press print the good news?” argument. In this case, of course, the objections were all dressed up and cleverly disguised as righteous indignation about the privacy of death. This is a form of puritanism that is often justifiable; just as often it is merely puritanical.

Seib takes it for granted that the widespread though fairly recent newspaper policy against printing pictures of dead bodies is a sound one; I don’t know that it makes any sense at all. I recognize that printing pictures of corpses raises all sorts of problems about taste and titillation and sensationalism; the fact is, however, that people die. Death happens to be one of life’s main events. And it is irresponsible — and more than that, inaccurate — for newspapers to fail to show it, or to show it only when an astonishing set of photos comes in over the Associated Press wire. Most papers covering fatal automobile accidents will print pictures of mangled cars. But the significance of fatal automobile accidents is not that a great deal of steel is twisted but that people die. Why not show it? That’s what accidents are about. Throughout the Vietnam War, editors were reluctant to print atrocity pictures. Why not print them? That’s what that was about. Murder victims are almost never photographed; they are granted their privacy. But their relatives are relentlessly pictured on their way in and out of hospitals and morgues and funerals.

I’m not advocating that newspapers print these things in order to teach their readers a lesson. The Post editors justified their printing of the Boston pictures with several arguments in that direction; every one of them is irrelevant. The pictures don’t show anything about slum life; the incident could have happened anywhere, and it did. It is extremely unlikely that anyone who saw them rushed out and had his fire escape strengthened. And the pictures were not news — at least they were not national news. It is not news in Washington, or New York, or Los Angeles that a woman was killed in a Boston fire. The only newsworthy thing about the pictures is that they were taken. They deserve to be printed because they are great pictures, breathtaking pictures of something that happened. That they disturb readers is exactly as it should be: that’s why photojournalism is often more powerful than written journalism.

Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing

In paragraph 5, Nora Ephron refers to “the famous assassination picture of the Vietcong prisoner in Saigon” (see Are Some Images Not Fit to Be Shown?). The photo shows the face of a prisoner who is about to be shot in the head at close range. Jot down the reasons why you would or would not approve of printing this photo in a newspaper. Think, too, about this: If the photo on page 154 weren’t about a war — if it didn’t include the soldiers and the burning village in the rear but, instead, showed children fleeing from an abusive parent or an abusive sibling — would you approve of printing it in a newspaper?

In paragraph 9, Ephron quotes a newspaperman as saying that before printing Forman’s pictures of the woman and the child falling from the fire escape, editors should have asked themselves “what purpose they served and what their effect was likely to be on the reader.” If you were an editor, what would your answers be? By the way, the pictures were not taken in a poor neighborhood, and they did not expose slum conditions.

In 50 words or so, write a precise description of what you see in the third of the Boston photographs. Do you think readers of your description would be “revolted” by the picture (para. 8), as were many viewers, the Washington Post’s ombudsman among them? Why, or why not?

Ephron thinks it would be good for newspapers to publish more photographs of death and dying (paras. 11–13). In an essay of approximately 500 words, state her reasons and your evaluation of them.