Are Some Images Not Fit to Be Shown?

Images of suffering — either human or animal — can be immensely persuasive. In the nineteenth century, for instance, the antislavery movement made extremely effective use of images in its campaign. We reproduce two antislavery images earlier in this chapter, as well as a counterimage that sought to assure viewers that slavery is a beneficent system. But are there some images not fit to print?

Until recently, many newspapers did not print pictures of lynched African Americans, hanged and burned and maimed. The reasons for not printing such images probably differed between South and North: Southern papers may have considered the images to be discreditable to whites, while northern papers may have deemed the images too revolting. Even today, when it’s commonplace for newspapers and television news to show pictures of dead victims of war, famine, or traffic accidents, one rarely sees bodies that are horribly maimed. (For traffic accidents, the body is usually covered, and we see only the smashed car.) The U.S. government has refused to release photographs showing the bodies of American soldiers killed in the war in Iraq, and it has been most reluctant to show pictures of dead Iraqi soldiers and civilians. Only after many Iraqis refused to believe that former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein’s two sons had been killed did the U.S. government reluctantly release pictures showing the two men’s blood-spattered faces — and some American newspapers and television programs refused to use the images.

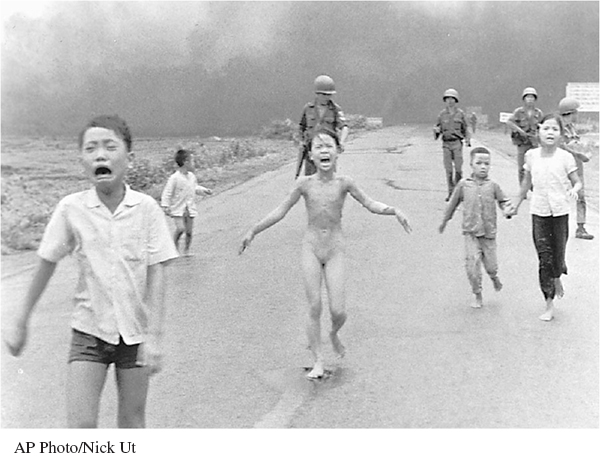

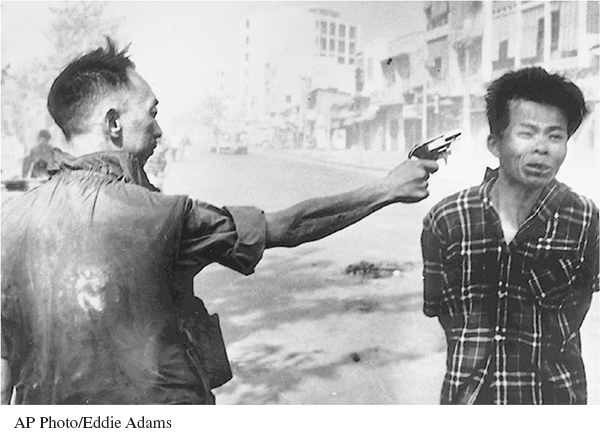

There have been notable exceptions to this practice, such as Huynh Cong (Nick) Ut’s 1972 photograph of children fleeing a napalm attack in Vietnam (below), which was widely reproduced in the United States and won the photographer a Pulitzer Prize in 1973. It’s impossible to measure the influence of this particular photograph, but many people believe that it played a substantial role in increasing public pressure to end the Vietnam War. Another widely reproduced picture of horrifying violence is Eddie Adams’s 1968 picture of a South Vietnamese chief of police firing a pistol into the head of a Viet Cong prisoner.

The issue remains: Are some images unacceptable? For instance, although capital punishment — by methods including lethal injection, hanging, shooting, and electrocution — is legal in parts of the United States, every state in the Union prohibits the publication of pictures showing a criminal being executed.1

The most famous recent example of an image widely thought to be unprintable showed the murder of Daniel Pearl, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal. Pearl was captured and murdered in June 2002 by Islamic terrorists in Pakistan. His killers videotaped Pearl reading a statement denouncing American policy and then being decapitated. The video also shows a man’s arm holding Pearl’s head. The video ends with the killers making demands (such as the release of Muslim prisoners being held by the United States in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba) and asserting, “if our demands are not met, this scene will be repeated again and again.”

The chief arguments against newspapers reproducing material from this video were as follows:

The video and still images from it are unbearably gruesome.

Showing the video would traumatize the Pearl family.

The video is enemy propaganda.

Those who favored broadcasting the video on television and printing still images from it in newspapers offered these arguments:

The photos would show the world what sort of enemy the United States is fighting.

Newspapers have published pictures of other terrifying sights (notably, people leaping out of windows of the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers on 9/11 and the space shuttle Challenger exploding in 1986).

No one was worried about protecting the families of 9/11 or Challenger victims from seeing those traumatic images.

But is the comparison of the Daniel Pearl video to the photos of the Twin Towers and the Challenger valid? You may respond that individuals in the Twin Towers pictures aren’t specifically identifiable and that the Challenger images, although horrifying, aren’t as visually revolting as the picture of a severed head held up for view.

The Boston Phoenix, a weekly newspaper, published some images from the Pearl video and also put a link to the video (with a warning that the footage is “extremely graphic”) on its Web site. The weekly’s editor justified publication on the three grounds we list above. Pearl’s wife, Mariane Pearl, was quoted in various newspapers as condemning the “heartless decision to air this despicable video.” And a spokeswoman for the Pearl family, when asked for comment, referred reporters to a statement issued earlier, which said that broadcasters who show the video

fall without shame into the terrorists’ plan. . . . Danny believed that journalism was a tool to report the truth and foster understanding — not perpetuate propaganda and sensationalize tragedy. We had hoped that no part of this tape would ever see the light of day. . . . We urge all networks and news outlets to exercise responsibility and not aid the terrorists in spreading their message of hate and murder.2

Although some journalists expressed regret that Pearl’s family was distressed, they insisted that journalists have a right to reproduce such material and that the images can serve the valuable purpose of shocking viewers into awareness.

POLITICS AND PICTURES

Consider, too, the controversy that erupted in 1991, during the Persian Gulf War, when the U.S. government decided that news media would not be allowed to photograph coffins returning with the bodies of military personnel killed during the war. In later years the policy was sometimes ignored, but in 2003 the George W. Bush administration decreed that there would be “no arrival ceremony for, or media coverage of, deceased military personnel returning [from Iraq or Afghanistan] . . . to the Dover (Delaware) base.” The government enforced the policy strictly.

Members of the news media strongly protested, as did many others, chiefly on the basis of these arguments:

The administration was trying to sanitize the war; that is, the government was depriving the public of important information — images — that showed the war’s real cost.

Grief for the deaths of military personnel is not a matter only for the families of the deceased. The sacrifices were made on behalf of the nation, and the nation should be allowed to grieve. Canada and Britain have no such ban; when military coffins are transported there, the public lines the streets to honor the fallen warriors. In fact, in Canada a portion of the highway near the Canadian base has been renamed “Highway of Heroes.”

The coffins at Dover Air Force base are not identified by name, so there is no issue about intruding on the privacy of grieving families.

The chief arguments in defense of the ban were as follows:

Photographs violate the families’ privacy.

If the arrival of the coffins at Dover is publicized, some grieving families will think they should travel to Dover to be present when the bodies arrive. This may cause a financial hardship on the families.

If the families give their consent, the press is not barred from individual graveside ceremonies at hometown burials. The ban extends only to the coffins’ arrival at Dover Air Force Base.

In February 2009, President Obama changed the policy and permitted coverage of the transfer of bodily remains. In his Address to the Joint Session of Congress on February 24, 2009, he said, “For seven years we have been a nation at war. No longer will we hide its price.” On February 27, Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates announced that the government ban was lifted and that families will decide whether to allow photographs and videos of the “dignified transfer process at Dover.”

Exercise

In an argumentative essay of about 250 words — perhaps two or three paragraphs — give your view of the issue of permitting photos of military coffins. In an opening paragraph, you may want to both explain the issue and summarize the arguments that you reject. The second paragraph of a two-paragraph essay may present your reasons for rejecting those arguments. Additionally, you might devote a third paragraph to a more general reflection.

Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing

Marvin Kalb, a distinguished journalist, was quoted as saying that the public has a right to see the tape of Daniel Pearl’s murder but that “common sense, decency, [and] humanity would encourage editors . . . to say ‘no, it is not necessary to put this out.’ There is no urgent demand on the part of the American people to see Daniel Pearl’s death.” What is your view?

In June 2006, two American soldiers were captured in Iraq. Later their bodies were found, dismembered and beheaded. Should newspapers have shown photographs of the mutilated bodies? Why, or why not? (In July 2006, insurgents in Iraq posted images on the Internet showing a soldier’s severed head beside his body.)

Another issue concerning the appropriateness of showing certain images arose early in 2006. In September 2005, a Danish newspaper, accused of being afraid to show political cartoons that were hostile to Muslim terrorists, responded by publishing twelve cartoons. One cartoon showed the prophet Muhammad wearing a turban that looked like a bomb. The images at first didn’t arouse much attention, but when they were reprinted in Norway in January 2006, they attracted worldwide attention and outraged Muslims, most of whom regard any depiction of Muhammad as blasphemous. Some Muslims in various Islamic nations burned Danish embassies and engaged in other acts of violence. Most non-Muslims agreed that the images were in bad taste; and apparently in deference to Islamic sensibilities (but possibly also out of fear of reprisals), very few Western newspapers reprinted the cartoons when they covered the news events. Most newspapers (including the New York Times) merely described the images. The editors of these papers believed that readers should be told the news, but that because the drawings were so offensive to some persons, they should be described rather than reprinted. A controversy then arose: Do readers of a newspaper deserve to see the evidence for themselves, or can a newspaper adequately fulfill its mission by offering only a verbal description? These questions arose again after the 2007 bombing of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, and then after another mass shooting at the same newspaper in 2015 that claimed the lives of twelve editors and staff members.

Persons who argued that the images should be reproduced in the media generally made these points:

Newspapers should yield neither to the delicate sensibilities of some readers nor to threats of violence.

Jews for the most part do not believe that God should be depicted (the prohibition against “graven images” appears in Exodus 20:3), but they raise no objections to such Christian images as Michelangelo’s painting of God awakening Adam, depicted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Further, when Andres Serrano (a Christian) in 1989 exhibited a photograph of a small plastic crucifix submerged in urine, it outraged a wider public (several U.S. senators condemned it because the artist had received federal funds), but virtually all newspapers showed the image, and many even printed its title, Piss Christ. The subject was judged to be newsworthy, and the fact that some viewers would regard the image as blasphemous was not considered highly relevant.

Our society values freedom of speech, and newspapers should not be intimidated. When certain pictures are a matter of news, readers should be able to see them.

In contrast, opposing voices made these points:

Newspapers must recognize deep-seated religious beliefs. They should indeed report the news, but there is no reason to show images that some people regard as blasphemous. The images can be adequately described in words.

The Jewish response to Christian images of God, and even the tolerant Christians’ response to Serrano’s image of the crucifix immersed in urine, are irrelevant to the issue of whether a Western newspaper should represent images of the prophet Muhammad. Virtually all Muslims regard depictions of Muhammad as blasphemous, and that’s what counts.

Despite all the Western talk about freedom of the press, the press does not reproduce all images that become matters of news. For instance, news items about the sale of child pornography do not include images of the pornographic photos.

Exercises: Thinking about Images

Does the display of the Muhammad cartoons constitute an argument? If so, what is the conclusion, and what are the premises? If not, then what sort of statement, if any, does publishing these cartoons constitute?

Hugh Hewitt, an Evangelical Christian, offered a comparison to the cartoon of Muhammad wearing a bomblike turban. Suppose, he asked, an abortion clinic were bombed by someone claiming to be an Evangelical Christian. Would newspapers publish “a cartoon of Christ’s crown of thorns transformed into sticks of TNT”? Do you think they would? If you were the editor of a newspaper, would you? Why, or why not?

One American newspaper, the Boston Phoenix, didn’t publish any of the cartoons “out of fear of retaliation from the international brotherhood of radical and bloodthirsty Islamists who seek to impose their will on those who do not believe as they do. . . . We could not in good conscience place the men and women who work at the Phoenix and its related companies in physical jeopardy.” Evaluate this position.

A week after the 2015 attack on Charlie Hebdo, and in response to media hesitancy to re-publish the offending images of Muhammad, the Index on Censorship and several other journalistic organizations called for all newspapers to publish them simultaneously and globally on January 8, 2015. “This unspeakable act of violence has challenged and assailed the entire press,” said Lucie Morillon of Reporters Without Borders. “Journalism as a whole is in mourning. In the name of all those who have fallen in the defence of these fundamental values, we must continue Charlie Hebdo’s fight for the right to freedom of information.” Evaluate this position.