Finding Material

What strategy you use for finding good sources will depend on your topic. Researching a current issue in politics or popular culture may involve reading recent newspaper articles, scanning information on government Web sites, and locating current statistics. Other topics may be best tackled by seeking out books and scholarly journal articles that are less timely but more in-depth and analytical. You may want to supplement library and Web sources with your own fieldwork by conducting surveys or interviews.

Critical thinking is crucial to every step of the research process. Whatever strategy you use, remember that you will want to find material that is authoritative, represents a balanced approach to the issues, and is persuasive. As you choose your sources, bear in mind they will be serving as your “expert witnesses” as you make a case to your audience. Their quality and credibility are crucial to your argument.

If you find what seems to be an excellent source, look at some of the sources that this author repeatedly cites.

FINDING QUALITY INFORMATION ONLINE

The Web is a valuable source of information for many topics and less helpful for others. In general, if you’re looking for information on public policy, popular culture, current events, legal affairs, or any subject of interest to agencies of the federal or state government, the Web is likely to have useful material. If you’re looking for literary criticism or scholarly analysis of historical or social issues, you will be better off using library databases, described later in this chapter.

To make good use of the Web, try these strategies:

Use the most specific terms possible when using a general search engine; put phrases in quotes.

Use the advanced search option to limit a search to a domain (e.g., .gov for government sites) or by date (such as Web sites updated in the past week or month).

If you’re not sure which sites might be good ones for research, try starting with one of the selective directories listed below instead of a general search engine.

Page 266Consider which government agencies and organizations might be interested in your topic, and go directly to their Web sites.

Follow “about” links to see who is behind a Web site and why they put the information on the Web. If there is no “about” link, delete everything after the first slash in the URL to go to the parent site to see if it provides information.

Use clues in URLs to see where sites originate. For example, URLs containing .k12 are hosted at elementary and secondary schools, so they may be intended for a young audience; those ending in .gov are government agencies, so they tend to provide official information.

Always bear in mind that the sources you choose must be persuasive to your audience. Avoid sites that may be dismissed as unreliable or biased.

Some useful Web sites include the following:

Selective Web Site Directories

ipl2 www.ipl.org

Open Directory Project www.dmoz.org

Current News Sources

Google News news.google.com

Reuters www.reuters.com

WikiNews en.wikinews.org/wiki/Main_Page

World Newspapers www.world-newspapers.com

World Press www.worldpress.org

Digital Primary Sources

American Memory memory.loc.gov

American Rhetoric www.americanrhetoric.com

Avalon Project avalon.law.yale.edu/

National Archives www.archives.gov

Smithsonian Source www.smithsoniansource.org

Government Information

GPO Access gpo.gov/fdsys/

Thomas (federal legislation) thomas.loc.gov

U.S. Department of Labor www.dol.gov

Scholarly or Scientific Information

CiteSeer citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/

Google Scholar scholar.google.com

Microsoft Academic academic.microsoft.com/

Taylor and Francis Open Access Journals www.tandfonline.com/page/openaccess

Statistical Information

American FactFinder factfinder.census.gov/

Fedstats fedstats.sites.usa.gov/

Pew Global Attitudes Project pewglobal.org

U.S. Census Bureau www.census.gov

U.S. Data and Statistics www.usa.gov/statistics

United Nations Statistics Division unstats.un.org/

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Guide to U.S. and World Statistical Information http://www.bls.gov/bls/other.htm

A WORD ABOUT WIKIPEDIA Links to Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.org) often rise to the top of Web search results. This vast and decentralized site provides over a million articles on a wide variety of topics. However, anyone can contribute to the online encyclopedia, so the accuracy of articles varies, and in some cases, the coverage of a controversial issue is one-sided or disputed. Even when the articles are accurate, they provide only basic information. Wikipedia’s founder, Jimmy Wales, cautions students against using it as a source, except for obtaining general background knowledge: “You’re in college; don’t cite the encyclopedia.”1 Still, Wikipedia often provides valuable bibliographies that will help you to get going.

FINDING ARTICLES USING LIBRARY DATABASES

Your library has a wide range of general and specialized databases available through its Web site. Some databases provide references to articles (and perhaps abstracts or summaries) or may provide direct links to the entire text of articles. General and interdisciplinary databases include Academic Search Premier (produced by the EBSCOhost company) and Expanded Academic Index (from InfoTrac).

More specialized databases include PsycINFO (for psychology research) and ERIC (focused on topics in education). Others, such as JSTOR, are full-text digital archives of scholarly journals. You will likely have access to newspaper articles through LexisNexis or Proquest Newsstand, particularly useful for articles that are not available for free on the Web. Look at your library’s Web site to see what your options are, or stop by the reference desk for a quick personalized tutorial.

When using databases, first think through your topic using the listing and diagramming techniques described in Planning, Drafting, and Revising an Argument. List synonyms for your key search terms. As you search, look at words used in titles and descriptors for alternative ideas and make use of the “advanced search” option so that you can easily combine multiple terms. Rarely will you find exactly what you’re looking for right away. Try different search terms and different ways to narrow your topic.

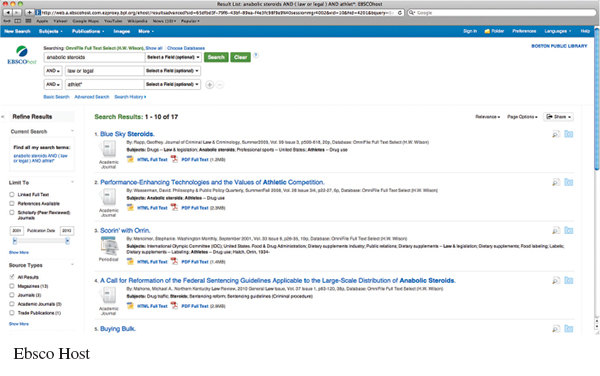

Most databases have an advanced search option that offers forms for combining multiple terms. In Figure 7.1, a search on “anabolic steroids” retrieved far too many articles. In this advanced search, three concepts are being combined in a search: anabolic steroids, legal aspects of their use, and use of them by athletes. Related terms are combined with the word “or”: law or legal. The last letters of a word have been replaced with an asterisk so that any ending will be included in the search. Athlet* will search for athlete, athletes, or athletics. Options on both sides of the list of articles retrieved offer opportunities to refine a search by date of publication or to restrict the results to only academic journals, magazines, or newspapers.

As with a Web search, you’ll need to make critical choices about which articles are worth pursuing. In this example, the first article may not be useful because it concerns German law. The second and third look fairly current and potentially useful. Only the third has a full text link, but the others may be available in another database. Many libraries have a program that will check other databases for you at the push of a button; in this case it’s indicated by the “Find full text” button.

As you choose sources, keep track of them by selecting them. Then you can print off, save, or e-mail yourself the references you have selected. You may also have an option to export references to a citation management program such as RefWorks or EndNote. These programs allow you to create your own personal database of sources in which you can store your references and take notes. Later, when you’re ready to create a bibliography, these programs will automatically format your references in MLA, APA, or another style. Ask a librarian if one of these programs is available to students on your campus.

LOCATING BOOKS

The books that your library owns can be found through its online catalog. Typically, you can search by author or title or, if you don’t have a specific book in mind, by keyword or subject. As with databases, think about different search terms to use, keeping an eye out for subject headings used for books that appear relevant. Take advantage of an “advanced search” option. You may, for example, be able to limit a search to books on a particular topic in English published within recent years. In addition to books, the catalog will also list DVDs, audio and video recordings, and other formats.

Unlike articles, books tend to cover broad topics, so be prepared to broaden your search terms. It may be that a book has a chapter or ten pages that are precisely what you need, but the catalog typically doesn’t index the contents of books in detail. Think instead of what kind of book might contain the information you need.

Once you’ve found some promising books in the catalog, note down the call numbers, find them on the shelves, and then browse. Since books on the same topic are shelved together, you can quickly see what additional books are available by scanning the shelves. As you browse, be sure to look for books that have been published recently enough for your purposes. You do not have to read a book cover-to-cover to use it in your research. Instead, skim the introduction to see if it will be useful, then use its table of contents and index to pinpoint the sections of the book that are the most relevant.

If you are searching for a very specific name or phrase, you might try typing it into Google Book Search (books.google.com), which searches the contents of over seven million scanned books. Though it tends to retrieve too many results for most topics, and you may only be able to see a snippet of content, it can help you locate a particular quote or identify which books might include an unusual name or phrase. There is a “find in a library” link that will help you determine whether the books are available in your library.