Instructor Notes

See the Additional Resources for Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing and reading comprehension quizzes for this chapter.

6

Developing an Argument of Your Own

The difficult part in an argument is not to defend one’s opinion but to know what it is.

— ANDRÉ MAUROIS

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally’s assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress.

— KENNETH BURKE

No greater misfortune could happen to anyone than that of developing a dislike for argument.

— PLATO

Planning, Drafting, and Revising an Argument

First, hear the wisdom of Mark Twain: “When the Lord finished the world, He pronounced it good. That is what I said about my first work, too. But Time, I tell you, Time takes the confidence out of these incautious early opinions.”

All of us, teachers and students, have our moments of confidence, but for the most part we know that it takes considerable effort to write clear, thoughtful, seemingly effortless prose. In a conversation we can cover ourselves with such expressions as “Well, I don’t know, but I sort of think . . .” and we can always revise our position (“Oh, well, I didn’t mean it that way”), but once we have handed in the final version of our writing, we are helpless. We are (putting it strongly) naked to our enemies.

GETTING IDEAS: ARGUMENT AS AN INSTRUMENT OF INQUIRY

In Chapter 1 we quoted Robert Frost, “To learn to write is to learn to have ideas,” and we offered suggestions about generating ideas, a process traditionally called invention. A moment ago we said that we often improve our ideas when explaining them to someone else. Partly, of course, we’re responding to questions or objections raised by our companion in the conversation. But partly we’re responding to ourselves: Almost as soon as we hear what we have to say, we may find that it won’t do, and if we’re lucky, we may find a better idea surfacing. One of the best ways of getting ideas is to talk things over.

The process of talking things over usually begins with the text that you’re reading: Your notes, your summary, and your annotations are a kind of dialogue between you and the author. You are also having a dialogue when you talk with friends about your topic. You are trying out and developing ideas. You’re arguing, but not chiefly to persuade; rather, you’re using argument in order to find the truth. Finally, after reading, taking notes, and talking, you may feel that you have some clear ideas and need only put them into writing. So you take up a sheet of blank paper, but then a paralyzing thought suddenly strikes: “I have ideas but just can’t put them into words.” The blank white page (or screen) stares back at you and you just can’t seem to begin.

All writers, even professional ones, are familiar with this experience. Good writers know that waiting for inspiration is usually not the best strategy. You may be waiting a long time. The best thing to do is begin. Recall some of what we said in Chapter 1: Writing is a way of thinking. It’s a way of getting and developing ideas. Argument is an instrument of inquiry as well as persuasion. It is an important part of critical thinking. It helps us clarify what we think. One reason we have trouble writing is our fear of putting ourselves on record, but another reason is our fear that we have no ideas worth putting down. However, by writing notes — or even free associations — and by writing a draft, no matter how weak, we can begin to think our way toward good ideas.

THREE BRAINSTORMING STRATEGIES: FREEWRITING, LISTING, AND DIAGRAMMING

If you are facing an issue, debate, or topic and don’t know what to write, this is likely because you don’t yet know what you think. If, after talking about the topic with yourself (via your reading notes) and others, you are still unclear on what you think, try one of these three strategies:

FREEWRITING Write for five or six minutes, nonstop, without censoring what you produce. You may use what you write to improve your thinking. You may even dim your computer screen so you won’t be tempted to look up and fiddle too soon with what you’ve just written. Once you have spent the time writing out your ideas, you can use what you’ve written to look further into the subject at hand.

Freewriting should be totally free. If you have some initial ideas, a good freewrite might look like this. (As a topic, let’s imagine the writer below is thinking about how children’s toys are constructed for different genders. The student is reflecting on the release of the Nerf Rebelle, a type of toy gun made specifically for girls.)

FREEWRITING: This year Nerf released a new toy made for girls, the Nerf Rebelle gun, an attempt the company made to offer toys for girls traditionally made for boys. This seems good — showing an effort toward equality between the sexes. Or is Nerf just trying to broaden its market and sell more toys (after all, boys are only half the population)? Or is it both? That could be my central question. But it is not like the gun makes no distinction between boys and girls. It is pink and purple and has feminine-looking designs on it. And with its “elle” ending the gun sounds small, cute, and girly. Does this toy represent true equality between the sexes, or does it just offer more in the way of feminine stereotypes? It shoots foam arrows, unlike the boys’ version of the gun, which shoots bullets. This suggests Cupid, maybe — that is, the figure whose arrows inspire love — a stereotype that girls aren’t saving the world but seeking love and marriage. Maybe it’s also related to Katniss Everdeen from the Hunger Games movie. She carries a bow and arrow, too. Like a lot of female superheroes, Katniss is presented as both strong and sexy, powerful and vulnerable, masculine and feminine at the same time. What kind of messages does this send to young girls? Is it the same message suggested by the gun? Why do powerful women have to project traditional or stereotypical femininity at the same time? How does this work in other areas of life, like business and politics?

Notice that the writer here is jumping around, generating and exploring ideas while writing. Later she can return to the freewriting and begin organizing her ideas and observations. Notice that right in the middle of the freewriting she made a connection between the toy and the Hunger Games movie, and by extension to the larger culture in which forms of contemporary femininity can be found. This connection seems significant, and it may help the student to broaden her argument from a critique of the company’s motives early on, to a more evidence-based piece about assumptions underlying certain trends in consumer and media culture. The point is that freewriting in this case led to new paths of inquiry and may have inspired further research into different kinds of toys and media.

LISTING Writing down keywords, just as you do when making a shopping list, is another way of generating ideas. When you make a shopping list, you write ketchup, and the act of writing it reminds you that you also need hamburger rolls — and that in turn reminds you that you also need tuna fish. Similarly, when preparing a list of ideas for a paper, just writing down one item will often generate another. Of course, when you look over the list, you’ll probably drop some of these ideas — the dinner menu will change — but you’ll be making progress. If you have a smartphone or tablet, use it to write down your thoughts. You can even e-mail these notes to yourself so you can access them later.

Here’s an example of a student listing questions and making associations that could help him focus on a specific argument within a larger debate. The subject here is whether prostitution should be legalized.

LIST: Prostitutes — Law — How has the law traditionally policed sex? — What types of prostitutes exist? — What is prostitution? — Where is it already legal? — How does it work in places where it is legal? — Individual rights vs. public good? — Why shouldn’t people be allowed to sell sex? — What are the “bad” effects of prostitution socially? — How many prostitutes are arrested every year? — Could prostitution be taxed? — Who suffers most from enforcement? — Who would suffer most if it were legal? — If it were legal, could its negative effects be better controlled? — Aren’t “escort services” really prostitution rings for people with more money? — How is that dealt with? — Who goes into the “oldest business” and why?

Notice that the student doesn’t really know the answers yet but is asking questions by free-associating and seeing what turns up as a productive line of analysis. The questions range from the definition of prostitution to its effects, and they might inspire the student to do some basic Internet research or even deeper research. Once you make a list, see if you can observe patterns or similarities among the items you listed, or if you invented a question worthy of its own thesis statement (e.g., “The enforcement of prostitution laws hurts X group unequally, and it uses a lot of public money that could better be used in other areas or toward regulating the trade rather than jailing people”).

DIAGRAMMING Sketching a visual representation of an essay is a kind of listing. Three methods of diagramming are especially common.

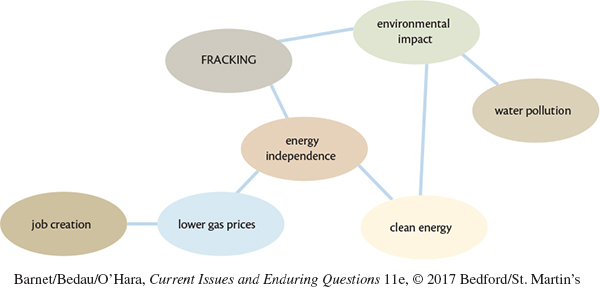

Clustering As we discuss in Thinking Through an Issue: Gay Marriage Licenses, you can make an effective cluster by writing, in the middle of a sheet of paper, a word or phrase summarizing your topic (e.g., fracking; see diagram below), circling it, and then writing down and circling a related word (e.g., energy independence). Perhaps this leads you to write lower gas prices and clean energy. You then circle these phrases and continue making connections. The next thing you think of is environmental impact, so you draw a line to clean energy. Then you think of water pollution, write it down and circle it, and draw another line to environmental impact. The next thing that occurs to you is job creation, so you write this down and circle it. You won’t connect this to clean energy, but you might connect it to lower gas prices because both are generally positive economic effects. (If you can think of negative economic impacts on other industries or workers, write them down and circle them.) Keep going, jotting down ideas and making connections where possible, indicating relationships. Notice that you appear to be detailing and weighing the economic and environmental impacts of fracking. Whether you realized it or not, an argument is taking shape.

Page 225

Page 225Branching Some writers find it useful to draw a tree, moving from the central topic to the main branches (chief ideas) and then to the twigs (aspects of the chief ideas).

Comparing in columns Draw a line down the middle of the page, and then set up two columns showing oppositions. For instance, if you are concerned with the environmental and economic impacts of fracking, you might head one column ENVIRONMENTAL and the other ECONOMIC. In the first column, you might write water pollution, chemicals used, and other hazards? In the second column, you might write clean air, employment, and independence from unstable oil-producing countries. You might go on to write, in the first column, gas leaks and toxic waste, and in the second, cheaper fuel and cheaper electricity — or whatever else relevant comes to mind.

All these methods can, of course, be executed with pen and paper, but you may also be able to use them on your computer depending on the capabilities of your software.

Whether you’re using a computer or a pen, you put down some words and almost immediately see that they need improvement, not simply a little polishing but a substantial overhaul. You write, “Race should be counted in college admissions for two reasons,” and as soon as you write those words, a third reason comes to mind. Or perhaps one of those “two reasons” no longer seems very good. As E. M. Forster said, “How can I know what I think till I see what I say?” We have to see what we say — we have to get something down on paper — before we realize that we need to make it better.

Writing, then, is really rewriting — that is, revising — and a revision is a re-vision, a second look. The essay that you submit — whether as hard copy or as a .doc file — should be clear and may appear to be effortlessly composed, but in all likelihood the clarity and apparent ease are the result of a struggle with yourself during which you refined your first thoughts. You begin by putting down ideas, perhaps in random order, but sooner or later comes the job of looking at them critically, developing what’s useful in them and removing what isn’t. If you follow this procedure you will be in the company of Picasso, who said that he “advanced by means of destruction.” Any passages that you cut or destroy can be kept in another file in case you want to revisit those deletions later. Sometimes, you end up restoring them and developing what you discarded into a new essay with a new direction.

Whether you advance bit by bit (writing a sentence, revising it, writing the next, etc.) or whether you write an entire first draft and then revise it and revise it again and again is chiefly a matter of temperament. Probably most people combine both approaches, backing up occasionally but trying to get to the end fairly soon so that they can see rather quickly what they know, or think they know, and can then start the real work of thinking, of converting their initial ideas into something substantial.

FURTHER INVENTION STRATEGIES: ASKING GOOD QUESTIONS

ASKING QUESTIONS Generating ideas, we said when talking about topics and invention strategies in Chapter 1 is mostly a matter of asking (and then thinking about) questions. In this book we include questions at the end of each argumentative essay, not to torment you but to help you think about the arguments — for instance, to turn your attention to especially important matters. If your instructor asks you to write an answer to one of these questions, you are lucky: Examining the question will stimulate your mind to work in a specific direction.

If your instructor doesn’t assign a topic for an argumentative essay, you’ll find that some ideas (possibly poor ones initially, but that doesn’t matter because you’ll soon revise) come to mind if you ask yourself questions. Begin determining where you stand on an issue (stasis) by asking the following five basic questions:

What is X?

What is the value of X?

What are the causes (or the consequences) of X?

What should (or ought or must) we do about X?

What is the evidence for my claims about X?

Let’s spend a moment looking at each of these questions.

1. What is X? We can hardly argue about the number of people sentenced to death in the United States in 2000 — a glance at the appropriate government report will give the answer — but we can argue about whether capital punishment as administered in the United States is discriminatory. Does the evidence support the view that in the United States the death penalty is unfair? Similarly, we can ask whether a human fetus is a human being (in saying what something is, must we take account of its potentiality?), and even if we agree that a fetus is a human being, we can further ask whether it is a person. In Roe v. Wade the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that even the “viable” unborn human fetus is not a “person” as that term is used in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Here the question is this: Is the essential fact about the fetus that it is a person?

An argument of this sort makes a claim — that is, it takes a stand; but notice that it does not also have to argue for an action. Thus, it may argue that the death penalty is administered unfairly — that’s a big enough issue — but it need not go on to argue that the death penalty should be abolished. After all, another possibility is that the death penalty should be administered fairly. The writer of the essay may be doing enough if he or she establishes the truth of the claim and leaves to others the possible responses.

2. What is the value of X? College courses often call for literary judgments. No one can argue if you say you prefer the plays of Tennessee Williams to those of Arthur Miller. But academic papers are not mere declarations of preferences. As soon as you say that Williams is a better playwright than Miller, you have based your preference on implicit standards, and you must support your preference by giving evidence about the relative skill, insight, and accomplishments of both Williams and Miller. Your argument is an evaluation. The question now at issue is the merits of the two authors and the standards appropriate for making such an appraisal.

In short, an essay offering an evaluation normally has two purposes:

to set forth an assessment

to convince the reader that the assessment is reasonable

In writing an evaluation, you have to rely on criteria, and these will vary depending on your topic. For instance, in comparing the artistic merit of plays by Williams and by Miller, you may want to talk about the quality of the characterization, the importance of the theme, and so on. But if the topic is “Which playwright is more suitable to be taught in high school?” other criteria may be appropriate, such as these:

the difficulty of the author’s language

the sexual content of some scenes

the presence of obscene words

Alternatively, consider a nonliterary issue: On balance, are college fraternities and sororities good or bad? If good, how good? If bad, how bad? What criteria serve best in making our evaluation? Probably some or all of the following:

testimony of authorities (e.g., persons who can offer firsthand testimony about the good or bad effects)

inductive evidence (examples of good or bad effects)

appeals to logic (“it follows, therefore, that . . .”)

appeals to emotion (e.g., an appeal to our sense of fairness)

3. What are the causes (or the consequences) of X? Why did the rate of auto theft increase during a specific period? If the death penalty is abolished, will that cause the rate of murder to increase? Problems such as these may be complex. The phenomena that people usually argue about — such as inflation, war, suicide, crime — have many causes, and it can be a mistake to speak of the cause of X. A writer in Time mentioned that the life expectancy of an average American male is about sixty-seven years, a figure that compares unfavorably with the life expectancy of males in Japan and Israel. The Time writer suggested that an important cause of the American male’s relatively short life span is “the pressure to perform well in business.” Perhaps. But the life expectancy of plumbers is no greater than that of managers and executives. Nutrition authority Jean Mayer, in an article in Life, attributed the relatively poor longevity of American males to a diet that is “rich in fat and poor in nutrients.” Doubtless other authorities propose other causes, and in all likelihood no one cause entirely accounts for the phenomenon.

Consider a second example of discussions of causality, this one concerning the academic performance of girls in single-sex elementary schools, middle schools, and high schools. It is pretty much agreed (based on statistical evidence) that the graduates of these schools do better, as a group, than girls who graduate from coeducational schools. Why do girls in single-sex schools tend, as a group, to do better? What is the cause? The administrators of girls’ schools usually attribute the success to the fact (we’re putting the matter bluntly here) that young women flourish better in an atmosphere free from male intimidation: They allegedly gain confidence and become more expressive when they aren’t threatened by the presence of males. This may be the answer, but skeptics have attributed the graduates’ success to two other causes:

Most single-sex schools require parents to pay tuition, and it is a documented fact that the children of well-to-do parents do better, academically, than the children of poor parents.

Most single-sex schools are private schools, and they select students from a pool of candidates. Admissions officers select those candidates who seem to be academically promising — that is, students who have already done well academically.

In short, the girls who graduate from single-sex schools may owe their later academic success not to the schools’ single-sex environment but to the fact that even at admission the students were academically stronger (again, we’re speaking of a cohort, not of individuals) than the girls who attend coeducational schools.

The lesson? Be cautious in attributing a cause. There may be several causes.

The kinds of support that usually accompany claims of cause include the following:

factual data, especially statistics

analogies (“The Roman Empire declined because of X and Y”; “Our society exhibits X and Y; therefore . . .”)

inductive evidence

4. What should (or ought or must) we do about X? Must we always obey the law? Should the law allow eighteen-year-olds to drink alcohol? Should eighteen-year-olds be drafted to do one year of social service? Should pornography be censored? Should steroid use by athletes be banned? Ought there to be Good Samaritan laws, making it a legal duty for a stranger to intervene to save a person from death or great bodily harm, when one might do so with little or no risk to oneself? These questions involve conduct and policy; how we answer them will reveal our values and principles.

An essay answering questions of this sort usually has the following characteristics:

It begins by explaining what the issue (the problem) is.

Then it states why the reader should care about the issue.

Next, it offers the proposed solution.

Then it considers alternative solutions.

Finally, it reaffirms the merit of the proposed solution, especially in light of the audience’s interests and needs.

You’ll recall that throughout this book we have spoken about devices that help a writer to generate ideas. If in drafting an essay concerned with policy you begin by writing down your thoughts on the five bulleted items listed above, you’ll almost surely uncover ideas that you didn’t know you had.

Support for claims of policy usually include the following:

statistics

appeals to common sense and to the reader’s moral sense

testimony of authorities

5. What is the evidence for my claims about X? In commenting on the four previous topics, we have talked about the kinds of support that writers commonly offer. However, a few additional points are important.

Critical reading, writing, and thinking depend on identifying and evaluating the evidence for and against the claims one makes and encounters in the writings of others. It isn’t enough to have an opinion or belief one way or the other; you need to be able to support your opinions — the bare fact of your sincere belief in what you say or write is not itself any evidence that what you believe is true.

What constitutes good reasons for opinions and adequate evidence for beliefs? The answer depends on the type of belief or opinion, assertion or hypothesis, claim or principle you want to assert. For example, there is good evidence that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, because this is the date for his death reported in standard almanacs. You could further substantiate the date by checking the back issues of the New York Times. But a different kind of evidence is needed to support the proposition that the chemical composition of water is H2O. And you would need still other kinds of evidence to support your beliefs about the likelihood of rain tomorrow, the probability that the Red Sox will win the pennant this year, the twelfth digit in the decimal expansion of pi, the average cumulative grades of graduating seniors over the past three years in your college, the relative merits of Hamlet and Death of a Salesman, and the moral dimensions of sexual harassment. None of these issues is merely a matter of opinion; yet about some of them, educated and informed people may disagree over the reasons, the evidence, and what they show. Sometimes, equally qualified experts examine the same evidence and draw different conclusions. Your job as a critical thinker is to be alert to the relevant reasons and evidence, as well as the basis of various conclusions, and to make the most of them as you present your views.

Again, an argument may answer two or more of our five basic questions. Someone who argues that pornography should (or should not) be censored will have to do the following:

Mark out the territory of the discussion by defining pornography (our first question: What is X?).

Examine the consequences of adopting the preferred policy (our third question).

Perhaps argue about the value of that policy (our second question). Some people maintain that pornography produces crime, but others maintain that it provides a harmless outlet for impulses that otherwise might vent themselves in criminal behavior.

Address the possible objection that censorship, however desirable on account of some of its consequences, may be unconstitutional and that even if censorship were constitutional, it would (or might) have undesirable side effects, such as repressing freedom of political opinion.

Keep in mind our fifth question: What is the evidence for my claims?

Thinking about one or more of these questions may get you going. For instance, thinking about What is X? will require you to produce a definition; and as you do this, new ideas might arise. If a question seems relevant, it’s a good idea to start writing — even just a fragmentary sentence. You’ll probably find that one word leads to another and that ideas begin to appear. Even if these ideas seem weak as you write them, don’t be discouraged; you will have put something on paper, and returning to these words, perhaps in five minutes or the next day, you’ll probably find that some aren’t at all bad and that others will stimulate you to better ones.

It may be useful to record your ideas in a special notebook or in a private digital notebook or document reserved for the purpose. Such a journal can be a valuable resource when it comes time to write your paper. Many students find it easier to focus their thoughts on writing if during the gestation period they’ve been jotting down relevant ideas on something more substantial than slips of paper or loose sheets. The very act of designating a traditional or digital notebook or document file as your journal for a course can be the first step in focusing your attention on the eventual need to write a paper.

Take advantage of the free tools at your disposal. Use the Internet and free Web tools, including RSS feeds, Google (Drive, sites, and others), Yahoo!, blogs, and wikis to organize your initial ideas and to solicit feedback. Talking with others can help, but sometimes there isn’t time to chat. By using an RSS feed on a Web site that you think will provide good information on your topic (or a topic you’re considering), you can receive notifications if the site has uploaded new material such as news links or op-eds. Posting a blog entry in a public space about your topic can also foster conversations about the topic and help you discover other opinions. Using the Internet to uncover and refine a topic is common practice, especially early in the research process.

If what we have just said doesn’t sound convincing, and if you know from experience that you have trouble getting started with writing, don’t despair. First aid is at hand in a sure-fire method that we will explain next.

THE THESIS OR MAIN POINT

Let’s assume that you are writing an argumentative essay — perhaps an evaluation of an argument in this book — and you have what seems to be a pretty good draft or at least a collection of notes that are the result of hard thinking. You really do have ideas now, and you want to present them effectively. How will you organize your essay? No one formula works best for every essayist and for every essay, but it is usually advisable to formulate a basic thesis (a claim, a central point, a chief position) and to state it early. Every essay that is any good, even a book-length one, has a thesis (a main point), which can be stated briefly — usually, in a sentence. Remember Coolidge’s remark on the preacher’s sermon on sin: “He was against it.” Don’t confuse the topic (sin) with the thesis (sin is bad). The thesis is the argumentative theme, the author’s primary claim or contention, the proposition that the rest of the essay will explain and defend. Of course, the thesis may sound commonplace, but the book or essay or sermon ought to develop it in an interesting and convincing way.

RAISING THE STAKES OF YOUR THESIS Imagine walking across campus and coming upon a person ready to perform on a tightrope suspended between two buildings. He is wearing a glittering leotard and is eyeing up his challenge very seriously. Here’s the thing, though: His tightrope is only one foot off the ground. Would you stop and watch him walk across it? Maybe, maybe not. Most people are likely to take a look and move on. If you did spend a few minutes watching, you wouldn’t be very worried about the performer falling. If he lost his balance momentarily, you wouldn’t gasp in horror. And if he walked across the tightrope masterfully, you might be somewhat impressed but not enraptured.

Now imagine the rope being a hundred feet off the ground. You and many others would almost certainly stop and witness the feat. The audience would likely be captivated, nervous about the performer potentially falling, “oohing” if he momentarily lost his balance, and cheering if he crossed the rope successfully.

Consider the tightrope as your thesis statement, the performer as writer, and the act of crossing as the argument. What we call “low-stakes” thesis statements are comparable to low tightropes: A low-stakes thesis statement itself may be interesting, but not much about it is vital to any particular audience. Low-stakes thesis statements lack a sense of importance or relevance. They may restate what is already widely known and accepted, or they may make a good point but not discuss any consequences. Some examples:

Good nutrition and exercise can lead to a healthy life.

Our education system focuses too much on standardized tests.

Children’s beauty pageants are exploitative.

Students can write well-organized, clear, and direct papers on these topics, but if the thesis is “low stakes” like these, then the performance would be similar to that of an expert walking across a tightrope one foot off the ground. The argument may be well executed, but few in the audience will be inspired by it.

However, if you raise the stakes by “raising the tightrope,” you can compel readers to want to read and keep reading. There are several ways to raise the tightrope. First, think about what is socially, culturally, or politically important about your thesis statement and argument. Some writing instructors tell students to ask themselves “so what?” about the thesis, but this can be a vague directive. Here are some better questions: Why is your thesis important? What is the impact of your thesis on a particular group or demographic? What are the consequences of what you claim? What could happen if your position were not recognized? How can your argument benefit readers or compel them to action (by doing something or adopting a new belief)? What will readers gain by accepting your argument as convincing?

A CHECKLIST FOR A THESIS STATEMENT

Consider the following questions:

Does the statement make an arguable assertion rather than (1) merely assert an unarguable fact, (2) merely announce a topic, or (3) declare an unarguable opinion or belief?

Is the statement broad enough to cover the entire argument that I will be presenting, and is it narrow enough for me to cover the topic in the space allotted?

In formulating your thesis, keep in mind these points:

Different thesis statements may speak to different target audiences. An argument about changes in estate tax laws may not thrill all audiences, but for a defined group — accountants, lawyers, or the elderly, for instance — this may be quite controversial and highly relevant.

Not all audiences are equal — or equally interested in your thesis or argument. In this book, we generally select topics of broad importance. However, in a literature course, a film history course, or a political science course, you’ll calibrate your thesis statements and arguments to an audience who is invested in those fields. In writing about the steep decline in bee populations, your argument might look quite different if you’re speaking to ecologists as opposed to gardeners. (We will discuss audience in greater detail in the following section.)

Be wary of compare-and-contrast arguments. One of the most basic approaches to writing is to compare and contrast, a maneuver that produces a low-tightrope thesis. It normally looks like this: “X and Y are similar in some ways and different in others.” But if you think about it, anything can be compared and contrasted in this way, and doing so doesn’t necessarily tell anything important. So, if you’re writing a compare-and-contrast paper, make sure to include the reasons why it is important to compare and contrast these things. What benefit does the comparison yield? What significance does it have to some audience, some area of knowledge, some field of study?

IMAGINING AN AUDIENCE

Raising the tightrope of your thesis will also require you to imagine the audience you’re addressing. The questions that you ask yourself in generating thoughts on a topic will primarily relate to the topic, but additional questions that consider the audience are always relevant:

Who are my readers?

What do they believe?

What common ground do we share?

Page 233What do I want my readers to believe?

What do they need to know?

Why should they care?

THINKING CRITICALLY “Walking the Tightrope”

Examine the low-stakes thesis statements provided below, and expand each one into a high-stakes thesis by including the importance of asserting it and by proposing a possible response. The first one has been done as an example.

| LOW-STAKES THESIS | HIGH-STAKES THESIS |

| Good nutrition and exercise can lead to a healthy life. | One way to help solve the epidemic obesity problem in the United States is to remind consumers of a basic fact accepted by nearly all reputable health experts: Good nutrition and exercise can lead to a healthy life. |

| Every qualified American should vote. | |

| Spanking children is good/bad. | |

| Electric cars will reduce air pollution. |

To complete this activity online, click here.

To complete this activity online, click here.

Let’s think about these questions. The literal answer to the first probably is “my teacher,” but (unless you receive instructions to the contrary) you should not write specifically for your teacher. Instead, you should write for an audience that is, generally speaking, like your classmates. In short, your imagined audience is literate, intelligent, and moderately well informed, but its members don’t know everything that you know, and they don’t know your response to the problem being addressed. Your audience needs more information along those lines to make an intelligent decision about the issue.

For example, in writing about how children’s toys shape the minds of young boys and girls differently, it may not be enough to simply say, “Toys are part of the gender socialization process.” (“Sure they are,” the audience might already agree.) However, if you raise the stakes, you have an opportunity to frame the questions that result from this observation: You frame the questions, lay out the issues, identify the problems, and note the complications that arise because of your basic thesis. You could point out that toys have a significant impact on the interests, identities, skills, and capabilities that children develop and carry into adulthood. Because toys are so significant, is it important to ask questions about whether they perpetuate gender-based stereotypes? Do toys help perpetuate social inequalities between the sexes? Most children think toys are “just fun,” but they may be teaching kids to conform unthinkingly to the social expectations of their sex, to accept designated sex-based social roles, and to cultivate talents differently based on sex. Is this a good or a bad thing? Do toys facilitate growth, or do they have any limiting effects?

What audiences should be concerned with your topic? Maybe you’re addressing the general public who buys toys for children at least some of the time. Maybe you’re addressing parents who are raising young children. Maybe you’re addressing consumer advocates, encouraging them to pressure toy manufacturers and retailers to produce more gender-neutral offerings. The point is that your essay should contain (and sustain) an assessment of the impact of your high-stakes thesis, and it should set out a clear course of action for a particular audience.

That said, if you know your audience well, you can argue for different courses of action that are most likely to be persuasive. You may not be very convincing if you argue to parents in general that they should never buy princess toys for their girls and avoid all Disney-themed toys. Perhaps you should argue simply that parents should be conscious of the gender messages that toys convey, offer their kids diverse toys, and talk to their children while playing with them about alternatives to the stereotypical messages that the toys convey. However, if you’re writing for a magazine called Radical Parenting and your essay is titled “Buying Toys the Gender-Neutral Way,” your audience and its expectations — therefore, your thesis and argument — may look far different. The bottom line is not just to know your audience but to define it.

The essays in this book are from many different sources with many different audiences. An essay from the New York Times addresses educated general readers; an essay from Ms. magazine targets readers sympathetic to feminism. An essay from Commonweal, a Roman Catholic publication for nonspecialists, is likely to differ in point of view or tone from one in Time, even though both articles may advance approximately the same position. The Commonweal article may, for example, effectively cite church fathers and distinguished Roman Catholic writers as authorities, whereas the Time article would probably cite few or none of these figures because a non-Catholic audience might be unfamiliar with them or, even if familiar, might be unimpressed by their views.

The tone as well as the gist of the argument is in some degree shaped by the audience. For instance, popular journals, such as National Review and Ms. Magazine, are more likely to use ridicule than are journals chiefly addressed to, say, an academic audience.

THE AUDIENCE AS COLLABORATOR

If you imagine a particular audience and ask yourself what it does and doesn’t need to be told, you will find that material comes to mind, just as when a friend asks you what a film you saw was about, who was in it, and how you liked it.

Your readers don’t have to be told that Thomas Jefferson was an American statesman in the early years of this country’s history, but they do have to be told that Elizabeth Cady Stanton was a late-nineteenth-century American feminist. Why? Because it’s your hunch that your classmates never heard of her, or even if they have heard the name, they can’t quite identify it. But what if your class has been assigned an essay by Stanton? In that case your imagined readers know Stanton’s name and at least a little about her, so you don’t have to identify her as an American of the nineteenth century. But you do still have to remind readers about relevant aspects of her essay, and you have to tell them about your responses to those aspects.

After all, even if the instructor has assigned an essay by Stanton, you cannot assume that your classmates know the essay inside out. You can’t say, “Stanton’s third reason is also unconvincing,” without reminding the reader, by means of a brief summary, of her third reason. Again:

Think of your classmates — people like you — as your imagined readers.

Be sure that your essay does not make unreasonable demands.

If you ask yourself,

“What do my readers need to know?” and

“What do I want them to believe?”

you will find some answers arising, and you will start writing.

We’ve said that you should imagine your audience as your classmates. But this isn’t the whole truth. In a sense, your argument is addressed not simply to your classmates but to the world interested in ideas. Even if you can reasonably assume that your classmates have read only one work by Stanton, you can’t begin your essay by writing, “Stanton’s essay is deceptively easy.” You have to name the work because it’s possible that a reader is familiar with some other work by Stanton. And by precisely identifying your subject, you ease the reader into your essay.

Similarly, you won’t open with a statement like this:

The majority opinion in Walker v. City of Birmingham held that . . .

Rather, you’ll write something like this:

In Walker v. City of Birmingham, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1966 that city authorities acted lawfully when they jailed Martin Luther King Jr. and other clergymen in 1963 for marching in Birmingham without a permit. Justice Potter Stewart delivered the majority opinion, which held that . . .

By the way, if you suffer from a writing block, the mere act of writing out such readily available facts will help you to get started. You’ll find that writing a few words, perhaps merely copying the essay’s title or an interesting quotation from the essay, will stimulate other thoughts that you didn’t know you had.

Here, again, are the questions about audience. If you write on a computer, consider putting these questions into a file. For each assignment, copy the questions into the file you’re working on, and then, as a way of generating ideas, enter your responses, indented, under each question.

Who are my readers?

What do they believe?

What common ground do we share?

What do I want my readers to believe?

What do they need to know?

Why should they care?

Thinking about your audience can help you get started; even more important, it can help you generate ideas. Our second and third questions about the audience (“What do they believe?” and “How much common ground do we share?”) will usually help you get ideas flowing.

Presumably, your imagined audience does not share your views, or at least does not fully share them. But why?

How can these readers hold a position that to you seems unreasonable?

By putting yourself into your readers’ shoes — and your essay will almost surely summarize the views that you’re going to speak against — and by thinking about what your audience knows or thinks it knows, you will generate ideas. Spend time online reviewing Web sites dedicated to your topic. What do they have to say, and why do the authors hold these views?

Let’s assume that you don’t believe that people should be allowed to smoke in enclosed public places, but you know that some people hold a different view. Why do they hold it? Try to state their view in a way that would be satisfactory to them. Having done so, you may perceive that your conclusions and theirs differ because they’re based on different premises — perhaps different ideas about human rights. Examine the opposition’s premises carefully, and explain, first to yourself and ultimately to your readers, why you find some of those premises to be unacceptable.

Perhaps some facts are in dispute, such as whether exposure to tobacco is harmful to nonsmokers. The thing to do, then, is to check the facts. If you find that harm to nonsmokers has not been proved but you nevertheless believe that smoking should be prohibited in enclosed public places, of course you can’t premise your argument on the wrongfulness of harming the innocent (in this case, the nonsmokers). You’ll have to develop arguments that take account of the facts.

Among the relevant facts there surely are some that your audience or your opponent will not dispute. The same is true of the values relevant to the discussion; both sides very likely believe in some of the same values (such as the principle mentioned above, that it is wrong to harm the innocent). These areas of shared agreement are crucial to effective persuasion in argument.

A RULE FOR WRITERS If you wish to persuade, you have to begin by finding premises that you can share with your audience.

There are two good reasons for identifying and isolating the areas of agreement:

There is no point in disputing facts or values on which you and your readers already agree.

It usually helps to establish goodwill between yourself and your opponent when you can point to shared beliefs, assumptions, facts, and values.

In a few moments we will return to the need to share some of the opposition’s ideas.

A CHECKLIST FOR IMAGINING AN AUDIENCE

Have I asked myself the following questions?

Who are my readers? How do I know?

How much about the topic do they already know?

Have I provided necessary background (including definitions of special terms) if the imagined readers probably are not especially familiar with the topic?

Are these imagined readers likely to be neutral? Sympathetic? Hostile? Have I done enough online research to offer something useful to a hostile audience?

If they’re neutral, have I offered good reasons to persuade them? If they’re sympathetic, have I done more than merely reaffirm their present beliefs? That is, have I perhaps enriched their views or encouraged them to act? If they’re hostile, have I taken account of their positions, recognized their strengths but also called attention to their limitations, and offered a position that might persuade these hostile readers to modify their position?

Recall that in composing college papers it’s usually best to write for a general audience, an audience rather like your classmates but without the specific knowledge that they all share as students enrolled in one course. If the topic is smoking in public places, the audience presumably consists of smokers and nonsmokers. Thinking about our fifth question on page 236 — “What do [readers] need to know?” — may prompt you to give statistics about the harmful effects of smoking. Or if you’re arguing on behalf of smokers, it may prompt you to cite studies claiming that no evidence conclusively demonstrates that cigarette smoking is harmful to nonsmokers. If indeed you are writing for a general audience and you are not advancing a highly unfamiliar view, our second question (“What does the audience believe?”) is less important here; but if the audience is specialized, such as an antismoking group, a group of restaurant owners who fear that antismoking regulations will interfere with their business, or a group of civil libertarians, an effective essay will have to address their special beliefs.

In addressing their beliefs (let’s assume that you don’t share them — at least, not fully), you must try to establish some common ground. If you advocate requiring restaurants to provide nonsmoking areas, you should recognize the possibility that this arrangement will result in inconvenience for the proprietor. But perhaps (the good news) the restaurant will regain some lost customers or attract some new customers. This thought should prompt you to think of other kinds of evidence — perhaps testimony or statistics.

When you formulate a thesis and ask questions about it — such as who the readers are, what they believe, what they know, and what they need to know — you begin to get ideas about how to organize the material (or, at least, you realize that you’ll have to work out some sort of organization). The thesis may be clear and simple, but the reasons (the argument) may take many pages. The thesis is the point; the argument sets forth the evidence that supports the thesis.

THE TITLE

It’s a good idea to announce the thesis in your essay’s title. If you scan the table of contents of this book, you’ll notice that a fair number of essayists use the title to let readers know, at least in a general way, what position they will advocate. Here are a few examples of titles that take a position:

Forgive Student Loans? Worst Idea Ever

Millennials Are Selfish and Entitled, and Helicopter Parents Are to Blame

The Draft Would Compel Us to Share the Sacrifice

True, these titles are not especially engaging, but the reader welcomes them because they give some information about the writer’s thesis.

Some titles don’t announce the thesis, but they do announce the topic:

Are We Slaves to Our Online Selves?

On Racist Speech

Should Governments Tax Unhealthy Foods and Drinks?

Although not clever or witty, the above titles are informative.

Some titles seek to attract attention or to stimulate the imagination:

A First Amendment Junkie

Why I Don’t Spare “Spare Change”

Building Baby from the Genes Up

All of these are effective, but a word of caution is appropriate here. In seeking to engage your readers’ attention, be careful not to sound like a wise guy. You want to engage the readers, not turn them off.

Finally, be prepared to rethink your title after completing the last draft of your paper. A title somewhat different from your working title may be an improvement because the finished paper may emphasize something entirely different from what you expected when you first gave it a title.

THE OPENING PARAGRAPHS

Opening paragraphs are difficult to write, so don’t worry about writing an effective opening when you’re drafting. Just get some words down on paper and keep going. But when you revise your first draft, you should begin to think seriously about the effect of your opening.

A good introduction arouses readers’ interest and prepares them for the rest of the paper. How? Opening paragraphs usually do at least one (and often all) of the following:

attract readers’ interest (often with a bold thesis statement or an interesting relevant statistic, quotation, or anecdote)

prepare readers by giving some idea of the topic and often of the thesis

give readers an idea of how the essay is organized

define a key term

You may not wish to announce your thesis in the title, but if you don’t announce it there, you should set it forth early in the argument, in the introductory paragraph or paragraphs. In an essay titled “Human Rights and Foreign Policy” (1982), U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Jeanne J. Kirkpatrick merely announces her topic (subject) as opposed to her thesis (point), but she hints at the thesis in her first paragraph, by deprecating President Jimmy Carter’s policy:

In this paper I deal with three broad subjects: first, the content and consequences of the Carter administration’s human rights policy; second, the prerequisites of a more adequate theory of human rights; and third, some characteristics of a more successful human rights policy.

Alternatively, consider this opening paragraph from Peter Singer’s “Animal Liberation”:

We are familiar with Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, and a variety of other movements. With Women’s Liberation some thought we had come to the end of the road. Discrimination on the basis of sex, it has been said, is the last form of discrimination that is universally accepted and practiced without pretense, even in those liberal circles which have long prided themselves on their freedom from racial discrimination. But one should always be wary of talking of “the last remaining form of discrimination.” If we have learned anything from the liberation movements, we should have learned how difficult it is to be aware of the ways in which we discriminate until they are forcefully pointed out to us. A liberation movement demands an expansion of our moral horizons, so that practices that were previously regarded as natural and inevitable are now seen as intolerable.

Although Singer’s introductory paragraph nowhere mentions animal liberation, in conjunction with the essay’s title it gives a good idea of what Singer is up to and where he is going. He knows that his audience will be skeptical, so he reminds them that in previous years many people were skeptical of reforms that are now taken for granted. He adopts a strategy used fairly often by writers who advance unconventional theses: Rather than beginning with a bold announcement of a thesis that may turn off some readers because it sounds offensive or absurd, Singer warms up his audience, gaining their interest by cautioning them politely that although they may at first be skeptical of animal liberation, if they stay with his essay they may come to feel that they have expanded their horizons.

Notice, too, that Singer begins by establishing common ground with his readers; he assumes, probably correctly, that they share his view that other forms of discrimination (now seen to be unjust) were once widely practiced and were assumed to be acceptable and natural. In this paragraph, then, Singer is not only showing himself to be fair-minded but is also letting readers know that he will advance a daring idea. His opening wins their attention and goodwill. A writer can hardly hope to do more. (Soon we’ll talk a little more about winning the audience.)

Keep in mind the following points when writing introductory paragraphs:

You may have to give background information that readers should keep in mind if they are to follow your essay.

You may wish to define some terms that are unfamiliar or that you use in an unusual sense.

If you’re writing for an online publication (where your instructor or audience will encounter your argument on the Web), you might establish a context for your argument by linking to a news video that outlines the topic, or you might offer your thesis and then link to a news story that supports your claim. (Remember that using any videos, images, or links also requires a citation of some kind.) The beauty of publishing the piece in an online environment is that you can link directly to sources and use them more easily than if you were submitting a hard copy.

After announcing the topic, giving the necessary background, and stating your position (and perhaps the opposition’s) in as engaging a manner as possible, you will do well to give the reader an idea of how you will proceed — that is, what the organization will be. In other words, use the introduction to set up the organization of your essay. Your instructors may assign four- to six-page mini-research papers or ten- to fifteen-page research papers; if they assign an online venue, ask them about the approximate word count. No matter what the length, every paper needs to have a clear organization. The introduction is where you can accomplish three key things:

A RULE FOR WRITERS In writing or revising introductory paragraphs, keep in mind this question: What do my readers need to know? Remember, your aim throughout is to write reader-friendly prose. Keeping the needs and interests of your audience constantly in mind will help you achieve this goal.

hook your reader

reveal your thesis and topic

explain how you will organize your discussion of the topic — what you’ll do first, second, third, and so on.

Look at Kirkpatrick’s opening paragraph for an illustration. She tells her readers that she will address three subjects, and she names them. Her approach in the paragraph is concise, obvious, and effective.

Similarly, you may want to announce fairly early that there are, say, four common objections to your thesis and that you will take them up one by one, beginning with the weakest (or most widely held) and moving to the strongest (or least familiar), after which you will advance your own view in greater detail. Not every argument begins with refuting the other side, though many arguments do. The point to remember is that you usually ought to tell readers where you will be taking them and by what route. In effect, you give them an outline.

ORGANIZING AND REVISING THE BODY OF THE ESSAY

We begin with a wise remark by a newspaper columnist, Robert Cromier: “The beautiful part of writing is that you don’t have to get it right the first time — unlike, say, a brain surgeon.”

In drafting an essay, you will of course begin with an organization that seems appropriate, but you may find, in rereading the draft, that some other organization is better. Here, for a start, is an organization that is common in argumentative essays:

Statement of the problem or issue

Statement of the structure of the essay (its organization)

Statement of alternative (but less adequate) solutions

Arguments in support of the proposed solution

Arguments answering possible objections

A summary, resolution, or conclusion

Let’s look at each of these six steps.

1. Statement of the problem or issue Whether the problem is stated briefly or at length depends on the nature of the problem and the writer’s audience. If you haven’t already defined unfamiliar terms or terms you use in a special way, now is the time to do so. In any case, it is advisable here to state the problem objectively (thereby gaining the reader’s trust) and to indicate why the reader should care about the issue.

2. Statement of the structure of the essay After stating the problem at the appropriate length, the writer often briefly indicates the structure of the rest of the essay. The structure used most frequently is suggested below, in points 3 and 4.

3. Statement of alternative (but less adequate) solutions In addition to stating the alternatives fairly (letting readers know that you’ve done your homework), the writer conveys a willingness to recognize not only the integrity of opposing proposals but also the (partial) merit of at least some of the alternative solutions.

Our point in the previous sentence is important and worth amplifying. Because it is important to convey your goodwill — your sense of fairness — to the reader, it’s advisable to show that you’re familiar with the opposition and that you recognize the integrity of those who hold that view. You accomplish this by granting its merits as far as you can. (For more about this approach, see the essay by Carl R. Rogers.)

The next stage, which constitutes most of the body of the essay, usually is this:

4. Arguments in support of the proposed solution The evidence offered will depend on the nature of the problem. Relevant statistics, authorities, examples, or analogies may come to mind or be available. This is usually the longest part of the essay.

5. Arguments answering possible objections These arguments may suggest the following:

The proposal won’t work (perhaps it is alleged to be too expensive, to make unrealistic demands on human nature, or to fail to reach the heart of the problem).

The proposed solution will create problems greater than the problem under discussion. (A good example of a proposal that produced dreadful unexpected results is the law mandating a prison term for anyone over age eighteen in possession of an illegal drug. Heroin dealers then began to use children as runners, and cocaine importers followed the practice.)

6. A summary, resolution, or conclusion Here the writer may seek to accommodate the opposition’s views as far as possible but clearly suggest that the writer’s own position makes good sense. A conclusion — the word comes from the Latin claudere, “to shut” — ought to provide a sense of closure, but it can be much more than a restatement of the writer’s thesis. It can, for instance, make a quiet emotional appeal by suggesting that the issue is important and that the ball is now in the reader’s court.

Of course, not every essay will follow this six-step pattern. But let’s assume that in the introductory paragraphs you have sketched the topic (and have shown, or implied, that the reader doubtless is interested in it) and have fairly and courteously set forth the opposition’s view, recognizing its merits (“I grant that,” “admittedly,” “it is true that”) and indicating the degree to which you can share part of that view. You now want to set forth arguments explaining why you differ on some essentials.

In presenting your own position, you can begin with either your strongest or your weakest reasons. Each method of organization has advantages and disadvantages.

If you begin with your strongest reason, the essay may seem to peter out.

If you begin with your weakest reason, you build to a climax; but readers may not still be with you because they may have felt at the start that the essay was frivolous.

The solution to the latter possibility is to ensure that even your weakest argument demonstrates strength. You can, moreover, assure your readers that stronger points will soon follow and you offer this point first in order to show that you are aware of it and that, slight though it is, it deserves some attention. The body of the essay, then, is devoted to arguing a position, which means offering not only supporting reasons but also refutations of possible objections to these reasons.

Doubtless you’ll sometimes be uncertain, while drafting an essay, whether to present a given point before or after another point. When you write, and certainly when you revise, try to put yourself into the reader’s shoes: Which point do you think the reader needs to know first? Which point leads to which further point? Your argument should not be a mere list of points; rather, it should clearly integrate one point with another in order to develop an idea. However, in all likelihood you won’t have a strong sense of the best organization until you have written a draft and have reread it.

CHECKING PARAGRAPHS When you revise a draft, watch out for short paragraphs. Although a paragraph of only two or three sentences (like some in this chapter) may occasionally be helpful as a transition between complicated points, most short paragraphs are undeveloped paragraphs. Newspaper editors favor very short paragraphs because they can be read rapidly when printed in the narrow columns typical of newspapers. Many of the essays reprinted in this book originally were published in newspapers and, thus, consist of very short paragraphs, but they should not be regarded as models for your own writing.

A RULE FOR WRITERS When you revise, make sure that your organization is clear to your readers.

A second note about paragraphs: Writers for online venues often “chunk” (i.e., they provide extra space for paragraph breaks) rather than write a continuous flow. These writers chunk their text for several reasons, but chiefly because breaking up paragraphs and adding space between them makes some types of writing “scannable”: The screen is easier to navigate because it isn’t packed with text in a 12-point font. The breaks in paragraphs also allow the reader to see a complete paragraph without having to scroll.

CHECKING TRANSITIONS Make sure, in revising, that the reader can move easily from the beginning of a paragraph to the end and from one paragraph to the next. Transitions help to signal the connections between units of the argument. For example (“For example” is a transition, indicating that an illustration will follow), they may illustrate, establish a sequence, connect logically, amplify, compare, contrast, summarize, or concede (see Thinking Critically: Using Transitions in Argument). Transitions serve as guideposts that enable the reader to move easily through your essay.

When writers revise an early draft, they chiefly do these tasks:

They unify the essay by eliminating irrelevancies.

They organize the essay by keeping in mind the imagined audience.

They clarify the essay by fleshing out thin paragraphs, by ensuring that the transitions are adequate, and by making certain that generalizations are adequately supported by concrete details and examples.

We are not talking here about polish or elegance; we are talking about fundamental matters. Be especially careful not to abuse the logical connectives (thus, as a result, and so on). If you write several sentences followed by therefore or a similar word or phrase, be sure that what you write after the therefore really does follow from what has gone before. Logical connectives are not mere transitional devices that link disconnected bits of prose. They are supposed to mark a real movement of thought, which is the essence of an argument.

THE ENDING

What about concluding paragraphs, in which you summarize the main points and reaffirm your position?

If you can look back over your essay and add something that both enriches it and wraps it up, fine; but don’t feel compelled to say, “Thus, in conclusion, I have argued X, Y, and Z, and I have refuted Jones.” After all, conclusion can have two meanings: (1) ending, or finish, as the ending of a joke or a novel; or (2) judgment or decision reached after deliberation. Your essay should finish effectively (the first sense), but it need not announce a judgment (the second).

If the essay is fairly short, so that a reader can keep its general gist in mind, you may not need to restate your view. Just make sure that you have covered the ground and that your last sentence is a good one. Notice that the student essay printed later in this chapter doesn’t end with a formal conclusion, although it ends conclusively, with a note of finality.

THINKING CRITICALLY Using Transitions in Argument

Fill in examples of the types of transitions listed below, using topics of your choice. The first one has been done as an example.

| TYPE OF TRANSITION | TYPE OF LANGUAGE USED | EXAMPLE OF TRANSITION |

| Illustrate | for example, for instance, consider this case | “Many television crime dramas contain scenes of graphic violence. For example, in the episode of Law and Order titled . . .” |

| Establish a sequence | a more important objection, a stronger example, the best reason | |

| Connect logically | thus, as a result, therefore, so, it follows | |

| Amplify | further, in addition to, moreover | |

| Compare | similarly, in a like manner, just as, analogously | |

| Contrast | on the one hand . . . on the other hand, in contrast, however, but | |

| Summarize | in short, briefly | |

| Concede | admittedly, granted, to be sure |

To complete this activity online, click here.

To complete this activity online, click here.

By “a note of finality” we do not mean a triumphant crowing. It’s far better to end with the suggestion that you hope you have by now indicated why those who hold a different view may want to modify it and accept yours.

If you study the essays in this book or the editorials and op-ed pieces in a newspaper, you will notice that writers often provide a sense of closure by using one of the following devices:

A RULE FOR WRITERS Emulate John Kenneth Galbraith, a distinguished writer on economics. Galbraith said that in his fifth drafts he regularly introduced the note of spontaneity for which his writing was famous.

a return to something stated in the introduction

a glance at the wider implications of the issue (e.g., if smoking is restricted, other liberties are threatened)

a hint toward unasked or answered questions that the audience might consider in light of the writer’s argument

a suggestion that the reader can take some specific action or do some further research (i.e., the ball is now in the reader’s court)

an anecdote that illustrates the thesis in an engaging way

a brief summary (Note: This sort of ending may seem unnecessary and tedious if the paper is short and the summary merely repeats what the writer has already said.)

TWO USES OF AN OUTLINE

THE OUTLINE AS A PRELIMINARY GUIDE Some writers sketch an outline as soon as they think they know what they want to say, even before writing a first draft. This procedure can be helpful in planning a tentative organization, but remember that in revising a draft you’ll likely generate some new ideas and have to modify the outline accordingly. A preliminary outline is chiefly useful as a means of getting going, not as a guide to the final essay.

THE OUTLINE AS A WAY OF CHECKING A DRAFT Whether or not you use a preliminary outline, we strongly suggest that after writing what you hope is your last draft, you make an outline of it; there is no better way of finding out whether the essay is well organized.

Go through the draft, and write down the chief points in the order in which you make them. That is, prepare a table of contents — perhaps a phrase for each paragraph. Next, examine your notes to see what kind of sequence they reveal in your paper:

Is the sequence reasonable? Can it be improved?

Are any passages irrelevant?

Does something important seem to be missing?

If no coherent structure or reasonable sequence clearly appears in the outline, then the full prose version of your argument probably doesn’t have any either. Therefore, produce another draft by moving things around, adding or subtracting paragraphs — cutting and pasting them into a new sequence, with transitions as needed — and then make another outline to see if the sequence now is satisfactory.

You’re probably familiar with the structure known as a formal outline. Major points are indicated by I, II, III; points within major points are indicated by A, B, C; divisions within A, B, C are indicated by 1, 2, 3; and so on. Thus:

Arguments for opening all Olympic sports to professionals

Fairness

Some Olympic sports are already open to professionals.

Some athletes who really are not professionals are classified as professionals.

Quality (achievements would be higher)

You may want to outline your draft according to this principle, or you might simply write a phrase for each paragraph and indent the subdivisions. But keep these points in mind:

It is not enough for the parts to be ordered reasonably.

The order must be made clear to the reader, usually by means of transitions such as for instance, on the one hand . . . on the other hand, we can now turn to an opposing view, and so on.

Here is another way of thinking about an outline. For each paragraph, write:

what the paragraph says, and

what the paragraph does.

An opening paragraph might be outlined thus:

What the paragraph says is that the words “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance should be omitted.

What the paragraph does is, first, inform the reader of the thesis, and second, provide some necessary background — for instance, that the words were not in the original wording of the Pledge.

A dual outline of this sort will help you to see whether you have a final draft or a draft that needs refinement.

A LAST WORD ABOUT OUTLINES

Outlines may seem rigid to many writers, especially to those who compose online, where we’re accustomed to cutting, copying, moving, and deleting as we draft. However, as mentioned earlier, an outline — whether you write it before drafting a single word or use it to evaluate the organization of something you’ve already written — is meant to be a guide rather than a straitjacket. Many writers who compose electronically find that the ability to keep banging out words — typing is so much easier than pushing a pen or pencil — and to cut and paste without actually reaching for scissors makes it easy to produce an essay that readers may find difficult to follow. (There is much truth in the proverb “Easy writing makes hard reading.”) If you compose electronically, and especially if you continually add, delete, and move text around without a clear organizational goal in mind, be sure to read and outline your draft, and then examine the outline to see if indeed there is a reasonable organization.

Outlines are especially helpful for long essays, but even short ones benefit from a bit of advanced planning, a list of a few topics (drawn from notes already taken) that keep the writer moving in an orderly way. A longer work such as an honors or a master’s thesis typically requires careful planning. An outline will be a great help in ensuring that you produce something that a reader can easily follow — but, of course, you may find as you write that the outline needs to be altered.

When readers reach the end of a piece of writing, they should feel that the writer has brought them to a decisive point and is not simply stopping abruptly and unexpectedly.

A CHECKLIST FOR ORGANIZING AN ARGUMENT

Does the introduction let the readers know where the author is taking them?

Does the introduction state the problem or issue?

Does it state the claim (the thesis)?

Does it suggest the organization of the essay, thereby helping the reader to follow the argument?

Do subsequent paragraphs support the claim?

Do they offer evidence?

Do they face objections to the claim and offer reasonable responses?

Do they indicate why the author’s claim is preferable?

Do transitions (signposts such as Furthermore, In contrast, and Consider as an example) guide the reader through the argument?

Does the essay end effectively, with a paragraph (at most, two paragraphs) bringing a note of closure — for instance, by indicating that the proposed solution is relatively simple? By admitting that although the proposed solution will be difficult to implement, it is certainly feasible? By reminding the reader of the urgency of the problem?

TONE AND THE WRITER’S PERSONA

Although this book is chiefly about argument in the sense of rational discourse — the presentation of reasons in support of a thesis or conclusion — the appeal to reason is only one form of persuasion. Another form is the appeal to emotion — to pity, for example. Aristotle saw, in addition to appeals to reason and to emotion, a third form of persuasion — the appeal to the speaker’s character. He called it the ethical appeal (the Greek word for this kind of appeal is ethos, meaning “character”). The idea is that effective speakers convey the suggestion that they are

informed,

intelligent,

fair minded (persons of goodwill), and

honest.

Because they are perceived as trustworthy, their words inspire confidence in their listeners. It is a fact that when reading an argument we’re often aware of the person or voice behind the words, and our assent to the argument depends partly on the extent to which we can share the speaker’s assumptions and see the matter from his or her point of view — in short, the extent to which we can identify with the speaker.

How can a writer inspire the confidence that lets readers identify with him or her? First, the writer should possess the virtues Aristotle specified: intelligence or good sense, honesty, and benevolence or goodwill. As a Roman proverb puts it, “No one gives what he does not have.” Still, possession of these qualities is not a guarantee that you will convey them in your writing. Like all other writers, you’ll have to revise your drafts so that these qualities become apparent; stated more moderately, you’ll have to revise so that nothing in the essay causes a reader to doubt your intelligence, honesty, and goodwill. A blunder in logic, a misleading quotation, a snide remark, even an error in spelling — all such slips can cause readers to withdraw their sympathy from the writer.

Of course, all good argumentative essays do not sound exactly alike; they do not all reveal the same speaker. Each writer develops his or her own voice, or (as literary critics and instructors call it) persona. In fact, one writer may have several voices or personae, depending on the topic and the audience. The president of the United States delivering an address on the State of the Union has one persona; when chatting with a reporter at his summer home, he has another. This change is not a matter of hypocrisy. Different circumstances call for different language. As a French writer put it, there is a time to speak of “Paris” and a time to speak of “the capital of the nation.” When Abraham Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg, he didn’t say “Eighty-seven years ago”; instead, he intoned “Four score and seven years ago.” We might say that just as some occasions required him to be the folksy Honest Abe, the occasion of the dedication of hallowed ground at Gettysburg, where so many Civil War soldiers lost their lives, required him to be formal and solemn — thus, as president of the United States he appropriately used biblical language. Lincoln’s election campaigns called for one persona, and the dedication of a military cemetery (an entirely different rhetorical situation) called for a different persona. For examples on how to vary tone, see Thinking Critically: Varying Tone.

A RULE FOR WRITERS Present yourself so that readers see you as knowledgeable, honest, open-minded, and interested in helping them to think about the significance of an issue.

When we talk about a writer’s persona, we mean the way in which the writer presents his or her attitudes

toward the self,

toward the audience, and

toward the subject.

Thus, if a writer says:

I have thought long and hard about this subject, and I can say with assurance that . . .

we may feel that he is a self-satisfied egotist who probably is mouthing other people’s opinions. Certainly he’s mouthing clichés: “long and hard,” “say with assurance.”