Re-viewing and Revising

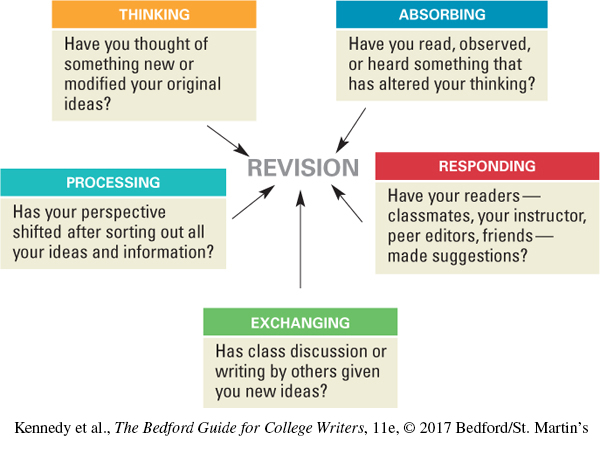

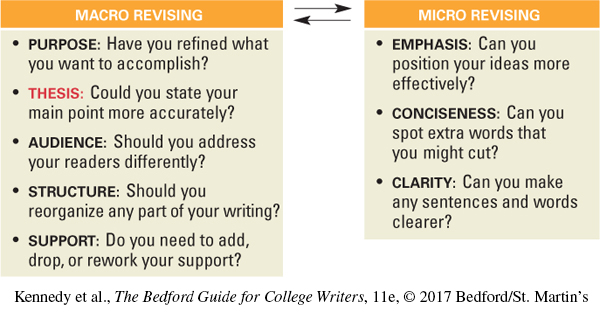

Revision means “seeing again”—discovering again, conceiving again, shaping again. It may occur at any and all stages of the writing process, and most writers do a lot of it. Macro revising is making large, global, or fundamental changes that affect the overall direction or impact of writing—its purpose, organization, or audience. Its companion is micro revising, paying attention to sentences, words, punctuation, and grammar—including ways to create emphasis and eliminate wordiness.

Revising for Purpose and Thesis

When you revise for purpose, you make sure that your writing accomplishes what you want it to do. If your goal is to create an interesting profile of a person, have you done so? If you want to persuade your readers to take a certain course of action, have you succeeded? When your project has evolved or your assignment grown clearer to you, the purpose of your final essay may differ from your purpose when you began. To revise for purpose, try to step back and see your writing as other readers will.

For more on stating and improving a working thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20. For checklists that will help you revise your thesis, see Chs. 4-12.

Concentrate on what’s actually in your paper, not what you assume is there. Create a thesis sentence (if you haven’t), or revise your working thesis statement (if you’ve developed one). Reconsider how it is worded:

Is it stated exactly in concise yet detailed language?

Is it focused on only one main idea?

Is it stated positively rather than negatively?

Is it limited to a demonstrable statement?

Then consider how accurately your thesis now represents your main idea:

Does each part of your essay directly relate to your thesis?

Does each part of your essay develop and support your thesis?

Does your essay deliver everything your thesis promises?

If you find unrelated or contradictory passages, you have several options: revise thesis, revise the essay, or revise both.

If your idea has deepened, your topic become more complex, or your essay developed along new lines, refine or expand your thesis accordingly.

| WORKING THESIS | The Herald’s coverage of the Senate elections was more thorough than the Courier’s. |

| REVISED THESIS | The Herald’s coverage of the Senate elections was less timely but more thorough and more impartial than the Courier’s. |

| WORKING THESIS | As the roles of men and women have changed in our society, old-fashioned formal courtesy has declined. |

| REVISED THESIS | As the roles of men and women have changed in our society, old-fashioned formal courtesy has declined not only toward women but also toward men. |

REVISION CHECKLIST

Do you know exactly what you want your essay to accomplish? Can you put it in one sentence: “In this paper I want to . . .”?

Is your thesis stated outright in the essay? If not, have you provided clues so that your readers will know precisely what it is?

Does every part of the essay work to achieve the same goal?

Have you tried to do too much? Does your coverage seem too thin? If so, how might you reduce the scope of your thesis and essay?

Does your essay say all that needs to be said? Is everything—ideas, connections, supporting evidence—on paper, not just in your head?

In writing the essay, have you changed your mind, rethought your assumptions, made a discovery? Does anything now need to be recast?

Have you developed enough evidence? Is it clear and convincing?

Revising for Audience

What works with one audience can fall flat with another. Your organization, selection of details, word choice, and tone all affect your particular readers. Visualize one of them poring over the essay, reacting to what you have written. What expressions do you see on that reader’s face? Where does he or she have trouble understanding? Where have you hit the mark?

REVISION CHECKLIST

Who will read this essay?

Will your readers think you have told them something worth knowing?

Page 445Are there any places where readers might fall asleep? If so, can you shorten, delete, or liven up such passages?

Does the opening of the essay mislead your readers by promising something that the essay never delivers?

Do you unfold each idea in enough detail to make it clear and interesting?

Have you anticipated questions your audience might ask?

Where might readers raise objections? How might you answer them?

Have you used any specialized or technical language that your readers might not understand? If so, have you worked in brief definitions?

What is your attitude toward your audience? Are you chummy, angry, superior, apologetic, preachy? Should you revise to improve your attitude?

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Audience

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Audience

Reflecting on Your Audience

Focus on the audience for a piece of writing that you are working on. (The audience for college writing typically will consist of your instructor and possibly your peers.) Is your word choice appropriate for this audience? Should you add or revise material to address the expectations of your readers or to give them the background they need to understand your subject? If your audience includes peer reviewers, what insights have they provided to help you improve your writing? After answering these questions, write a brief reflection on what you have learned about addressing audience needs and expectations.

Revising for Structure and Support

When you revise for structure and support, you make sure that the order of your ideas, your selection of supporting material, and its arrangement are as effective as possible. You may have all the ingredients of a successful essay—but they may be a confusing mess.

For more on paragraphs, topic sentences, and transitions, see Ch. 21.

In a well-structured essay, each paragraph, sentence, and phrase serves a clear function. Are your opening and closing paragraphs relevant, concise, and interesting? Is everything in each paragraph on the same topic? Are all ideas adequately developed? Are the paragraphs arranged in the best possible order? Finally, do you lead readers from one idea to the next with clear and painless transitions?

For more on using outlining for planning, see Organizing Your Ideas in Ch. 20.

An outline can help you discover what you’ve succeeded in getting on paper. Find the topic sentence of each paragraph in your draft (or create one, if necessary), and list them in order. Label the sentences I., II., A., B., and so on, to show the logical relationships of ideas. Do the same with the supporting details under each topic sentence, labeling them also with letters and numbers and indenting appropriately. Now look at the outline. Does it make sense on its own, without the essay to explain it? Would a different order or arrangement be more effective? Do any sections look thin and need more evidence? Are the connections between parts on paper, not just in your head? Maybe too many ideas are jammed into too few paragraphs. Maybe you need more specific details and examples—or stronger ones. Strengthen the outline and then rewrite to follow it.

REVISION CHECKLIST

Does your introduction set up the whole essay? Does it both grab readers’ attention and hint at what is to follow?

Does the essay fulfill all that you promise in your opening?

Would any later passage make a better beginning?

Is your thesis clear early in the essay? If explicit, is it positioned prominently?

Do the paragraph breaks seem logical?

Is the main idea of each paragraph clear? Is it stated in a topic sentence?

Is the main idea of each paragraph fully developed? Where might you need more or better evidence? Should you omit or move any stray bits?

Is each detail or piece of evidence relevant to the topic sentence of the paragraph and the main point of the essay?

Would any paragraphs make more sense in a different order?

Does everything follow clearly? Does one point smoothly lead to the next? Would transitions help make the connections clearer?

Does the conclusion follow logically or seem tacked on?

Learning by Doing Tackling Macro Revision

Learning by Doing Tackling Macro Revision

Tackling Macro Revision

Select a draft that would benefit from revision. Then, based on your sense of its greatest need, choose one of the revision checklists to guide a first revision. Let the draft sit for a while. Then work with one of the remaining checklists.

Working with a Peer Editor

There’s no substitute for having someone else read your draft. Whether you are writing for an audience of classmates or for a different group (the town council or readers of Time), having a classmate go over your essay is a worthwhile revision strategy. To gain all you can as a writer from a peer review, you need to play an active part:

Ask your reader questions. Or bring a “Dear Editor” letter or memo, written ahead, to your meeting.

Questions for a Peer Editor

First Questions for a Peer Editor

What is your first reaction to this paper?

What is this writer trying to tell you?

What are this paper’s greatest strengths?

Does it have any major weaknesses?

What one change would most improve the paper?

Questions on Meaning

Do you understand everything? Is the draft missing any information that you need to know?

Does this paper tell you anything you didn’t know before?

Is the writer trying to cover too much territory? Too little?

Does any point need to be more fully explained or illustrated?

When you come to the end, has the paper delivered what it promised?

Could this paper use a down-to-the-ground revision?

Questions on Organization

Does the beginning grab your interest and draw you into the main idea? Or can you find a better beginning at a later point?

Does the paper have one main idea, or does it juggle more than one?

Would the main idea stand out better if anything were removed or added?

Might the ideas in the paper be more effectively arranged? Do any ideas belong together that now seem too far apart?

Can you follow the ideas easily? Are transitions needed? If so, where?

Does the writer keep to one point of view—one angle of seeing?

Does the ending seem deliberate, as if the writer meant to conclude, not just run out of gas? How might the writer strengthen the conclusion?

Questions on Writing Strategies

Do you feel that this paper addresses you personally?

Do you dislike or object to any statement the writer makes or any wording the writer uses? Is the problem word choice, tone, or inadequate support to convince you? Should the writer keep or change this part?

Does the draft contain anything that distracts you or seems unnecessary?

Do you get bored at any point? How might the writer keep you reading?

Is the language of this paper too lofty and abstract? If so, where does the writer need to come down to earth and get specific?

Do you understand all the words used? Do any specialized words need clearer definitions?

Be open to new ideas—for focus, organization, or details.

Use what’s helpful, but trust yourself as the writer.

Be a helpful peer editor: offer honest, intelligent feedback, not judgment.

See specific checklists in the Revising and Editing sections in Chs. 4–12.

Look at the big picture: purpose, focus, thesis, clarity, coherence, organization, support.

When you spot strengths or weaknesses, be specific: note examples.

Answer the writer’s questions, and also use the questions supplied throughout this book to concentrate on essentials, not details.

Meeting with Your Instructor

Prepare for your conference on a draft as you prepare for a peer review. Reread your paper; then write out your questions, concerns, or current revision plans. Whether you are meeting face-to-face, online, or by audio or video phone, arrive on time. Even if you feel shy or anxious, remember that you are working with an experienced reader who wants to help you improve your writing.

If you already have received comments from your instructor, ask about anything you can’t read, don’t understand, or can’t figure out how to do.

If you are unsure about comments from peers, get your instructor’s view.

If you have a revision plan, ask for suggestions or priorities.

If more questions arise after your conference, especially about comments on a draft returned there, follow up with a call, e-mail message, question after class, or second conference (as your instructor prefers).

Decoding Your Instructor’s Comments

Many instructors favor two kinds of comments:

Summary comments—sentences on your first or last page—that may compliment strengths, identify recurring issues, acknowledge changes between drafts, make broad suggestions, or end with a grade

Specific comments—brief notes or questions added in the margins—that typically pinpoint issues in the text

Although brief comments may seem like cryptic code or shorthand, they usually rely on key words to note common, recurring problems that probably are discussed in class and related to course criteria. They also may act as reminders, identifying issues that your instructor expects you to look up in your book and solve. A simple analysis—tallying up the repeated comments in one paper or several—can quickly help you set priorities for revision and editing. Some sample comments follow with translations, but turn to your instructor if you need a specific explanation.

| COMMENTS ON PURPOSE | Thesis? Vague Broad Clarify What’s your point? So? So what? |

| POSSIBLE TRANSLATION | You need to state your thesis more clearly and directly so that a reader knows what matters. Concentrate on rewording so that your main idea is plain. |

|

Page 449

COMMENTS ON ORGANIZATION

|

Hard to follow Logic? Sequence? Add transitions? Jumpy |

| POSSIBLE TRANSLATION | You need to organize more logically so your paper is easy for a reader to follow without jumping from point to point. Add transitions or other cues to guide a reader. |

| COMMENTS ON SENTENCES AND WORDS | Unclear Clarify Awk Repetition Too informal |

| POSSIBLE TRANSLATION | You need to make your sentence or your wording easier to read and clearer. Rework awkward passages, reduce repetition, and stick to academic language. |

| COMMENTS ON EVIDENCE | Specify Focus Narrow down Develop more Seems thin |

| POSSIBLE TRANSLATION | You need to provide more concrete evidence or explain the relevance or nature of your evidence more clearly. Check that you support each main point with plenty of pertinent and compelling evidence. |

| COMMENTS ON SOURCES | Likely opponents? Source? Add quotation marks? Too many quotes Summarize? Synthesize? Launch source? |

| POSSIBLE TRANSLATION | You need to add sources that represent views other than your own. You include wording or ideas that sound like a source, not like you, so your quotation marks or citation might be missing. Instead of tossing in quotations, use your critical thinking skills to sum up ideas, relate them to each other, and introduce them more effectively. |

| COMMENTS ON CITATIONS | Cite? Author? Page? MLA? APA? |

| POSSIBLE TRANSLATION | Add missing source citations in your text and use the expected academic format to present them. |

| COMMENTS ON FINAL LIST OF SOURCES | MLA? APA? Comma? Period? Cap? Space? |

| POSSIBLE TRANSLATION | Your entries do not follow the expected format. Check the model entries in this book. Look for the presence, absence, or placement of the specific detail noted. |