Revising for Emphasis, Conciseness, and Clarity

After you’ve revised for the large issues in your draft—purpose, thesis, audience, structure, and support—you’re ready to turn your attention to micro revising. Now is the time to look at your language, to emphasize what matters most, and to communicate it concisely and clearly. Your close attention to these aspects of your draft also can strengthen your distinctive voice and style as a writer.

Stressing What Counts

An effective writer decides what matters most and shines a bright light on it using the most emphatic positions in an essay, a paragraph, or a sentence—the beginning and the end.

Stating It First. In an essay, you might start with what matters most. For an economics paper on import quotas (such as the number of foreign cars allowed into a country), student Donna Waite summed up her conclusion.

Although an import quota has many effects, both for the nation imposing the quota and for the nation whose industries must suffer from it, I believe that the most important effect is generally felt at home. A native industry gains a chance to thrive in a marketplace of lessened competition.

To take a stand or make a proposal, you might open with your position.

Our state’s antiquated system of justices of the peace is inefficient.

The United States should orbit a human observer around Mars.

In a single sentence, as in an essay, you can stress things at the start. Consider the following unemphatic sentence:

When Congress debates the Hall-Hayes Act removing existing protections for endangered species, as now seems likely to occur on May 12, it will be a considerable misfortune if this bill should pass, since the extinction of many rare birds and animals would certainly result.

The debate and its probable timing consume the start of the sentence. Here’s a better use of this emphatic position:

The extinction of many rare birds and animals would certainly follow passage of the Hall-Hayes Act.

Now the writer stresses what he most fears—the dire consequences of the act. (A later sentence might add the date and his opinion about passage.)

Stating It Last. To place an idea last can throw weight on it. Emphatic order, proceeding from least important to most, is dramatic: it builds up and up. In a paper on import quotas, however, a dramatic buildup might look contrived. Still, in an essay on how city parks lure visitors to the city, thesis sentence—summing up the point of the essay—might stand at the very end: “For the urban core, improved parks could bring about a new era of prosperity.” Giving evidence first and leading up to thesis at the end is particularly effective in editorials and informal persuasive essays.

A sentence that uses climactic order, suspending its point until the end, is a periodic sentence as novelist Julian Green illustrates.

Amid chaos of illusions into which we are cast headlong, there is one thing that stands out as true, and that is—love.

Cutting and Whittling

Like pea pickers who throw out dirt and pebbles, good writers remove needless words that clog their prose. One of the chief joys of revising is to watch 200 meandering words shrink to a direct 150. To see how saving words helps, let’s look at some strategies for reducing wordiness.

For more on stating a thesis, see Stating and Using a Thesis in Ch. 20.

Cut the Fanfare. Why bother to announce that you’re going to say something? Cut the fanfare. We aren’t, by the way, attacking the usefulness of transitions that lead readers along.

| WORDY | As far as getting ready for winter is concerned, I put antifreeze in my car. |

| REVISED | To get ready for winter, I put antifreeze in my car. |

| WORDY |

The point should be made that . . . Let me make it perfectly clear that . . . In this paper I intend to . . . In conclusion I would like to say that . . . |

Use Strong Verbs. Forms of the verb be (am, is, are, was, were) followed by a noun or an adjective can make a statement wordy, as can There is or There are. Such weak verbs can almost always be replaced by active verbs.

| WORDY | The Akron game was a disappointment to the fans. |

| REVISED | The Akron game disappointed the fans. |

| WORDY | There are many people who dislike flying. |

| REVISED | Many people dislike flying. |

Use Relative Pronouns with Caution. When a clause begins with a relative pronoun (who, which, that), you often can whittle it to a phrase.

| WORDY | Venus, which is the second planet of the solar system, is called the evening star. |

| REVISED | Venus, the second planet of the solar system, is called the evening star. |

Cut Out Deadwood. The more you revise, the more shortcuts you’ll discover. Phrases such as on the subject of, in regard to, in terms of, and as far as . . . is concerned often simply fill space. Try reading the sentences below without the words in italics.

Howell spoke for the sophomores, and Janet also spoke for the seniors.

He is something of a clown but sort of the lovable type.

As a major in the field of economics, I plan to concentrate on the area of international banking.

The decision as to whether or not to go is up to you.

Cut Descriptors. Adjectives and adverbs are often dispensable.

| WORDY | Johnson’s extremely significant research led to highly important major discoveries. |

| REVISED | Johnson’s research led to major discoveries. |

Be Short, Not Long. While a long word may convey a shade of meaning that a shorter synonym doesn’t, in general favor short words over long ones. Instead of the remainder, write the rest; instead of activate, start or begin; instead of adequate or sufficient, enough. Look for the right word—one that wraps an idea in a smaller package.

| WORDY | Andy has a left fist that has a lot of power in it. |

| REVISED | Andy has a potent left. |

By the way, it pays to read. From reading, you absorb words like potent and set them to work for you.

Keeping It Clear

Recall what you want to achieve—clear, direct communication with your readers using specific, unambiguous words arranged in logical order.

| WORDY | He is more or less a pretty outstanding person in regard to good looks. |

| REVISED | He is strikingly handsome. |

Read your draft with fresh eyes. Return, after a break, to passages that have been a struggle; heal any battle scars by focusing on clarity.

| UNCLEAR | Thus, after a lot of thought, it should be approved by the board even though the federal funding for all the cow-tagging may not be approved yet because it has wide support from local cattle ranchers. |

| CLEAR | In anticipation of federal funding, the Livestock Board should approve the cow-tagging proposal widely supported by local cattle ranchers. |

MICRO REVISION CHECKLIST

Have you positioned what counts at the beginning or the end?

Are you direct, straightforward, and clear?

Do you announce an idea before you utter it? If so, consider chopping out the announcement.

Can you substitute an active verb where you use a form of be (is, was, were)?

Can you recast any sentence that begins There is or There are?

Can you reduce to a phrase any clause beginning with which, who, or that?

Have you added deadwood or too many adjectives and adverbs?

Do you see any long words where short words would do?

Have you kept your writing clear, direct, and forceful?

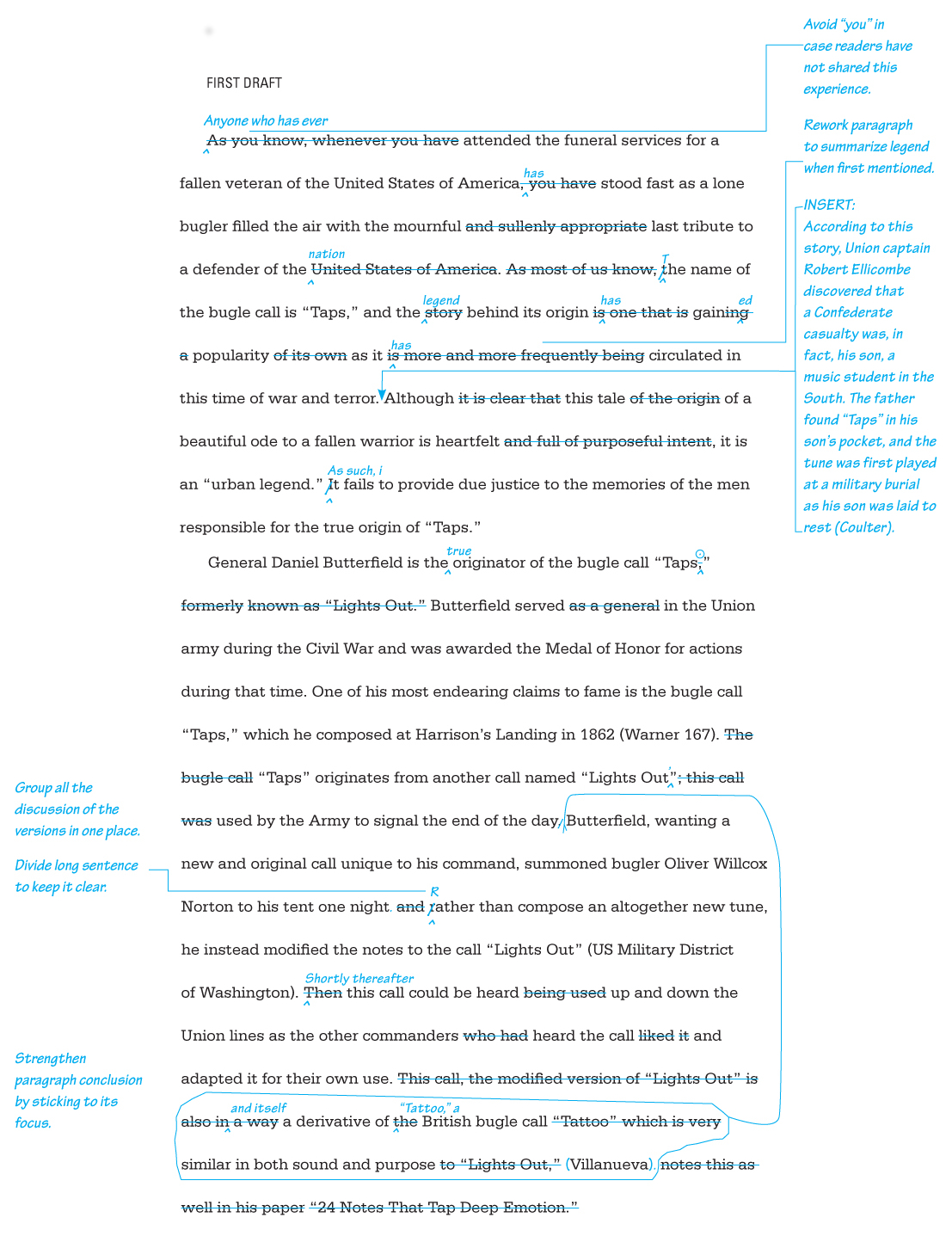

For his composition class, Daniel Matthews was assigned a paper using a few sources. He was to write about an “urban legend,” a widely accepted and emotionally appealing—but untrue—tale about events. The following selection from his paper, “The Truth about ‘Taps,’” introduces his topic, briefly explaining the legend and the true story about it. The first draft illustrates macro revisions (highlighted in the margin) and micro revisions (marked in the text); the clear and concise final version follows.

REVISED DRAFT

Anyone who has ever attended the funeral services for a fallen veteran of the United States of America has stood fast as a lone bugler filled the air with a mournful last tribute to a defender of the nation. The name of the bugle call is “Taps,” and the legend behind its origin has gained popularity as it has circulated in this time of war and terror. According to this story, Union captain Robert Ellicombe discovered that a Confederate casualty was, in fact, his son, a music student in the South. The father found “Taps” in his son’s pocket, and the tune was first played at a military burial as his son was laid to rest (Coulter). Although this tale of a beautiful ode to a fallen warrior is heartfelt, it is an “urban legend.” As such, it fails to provide due justice to the memories of the men responsible for the true origin of “Taps.”

General Daniel Butterfield is the true originator of the bugle call “Taps.” Butterfield served in the Union army during the Civil War and was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions during that time. One of his most endearing claims to fame is the bugle call “Taps,” which he composed at Harrison’s Landing in 1862 (Warner 167).“Taps” originates from another call named “Lights Out,” used by the army to signal the end of the day and itself a derivative of “Tattoo,” a British bugle call similar in both sound and purpose (Villanueva). Butterfield, wanting a new and original call unique to his command, summoned bugler Oliver Willcox Norton to his tent one night. Rather than compose an altogether new tune, he instead modified the notes to the call “Lights Out” (US Military District of Washington). Shortly thereafter this call could be heard up and down the Union lines as other commanders heard the call and adapted it for their own use.