A Process of Critical Reading

For more on critical thinking, see Ch. 3.

Reading critically means approaching whatever you read in an active, questioning manner. This essential college-level skill changes reading from a spectator sport to a contact sport. You no longer sit in the stands, watching graceful skaters glide by. Instead, you charge right into a rough-and-tumble hockey game, gripping your stick and watching out for your teeth.

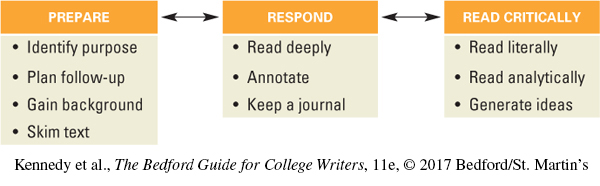

Critical reading, like critical thinking, is not an activity reserved for college courses. It is a continuum of strategies that thoughtful people use every day to grapple with new information, to integrate it with existing knowledge, and to apply it to problems in daily life:

They get ready to do their reading.

They respond as they read.

They read on literal and analytical levels.

Building your critical reading skills will open the door to information you’ve never encountered and to ideas unlikely to come up with friends. For this course alone, you will be prepared to evaluate strengths and weaknesses of essays by professionals, students, and classmates. If you research a topic, you will be ready to figure out what your sources say, what they assume and imply, whether they are sound, and how you might use them to help make your point. In addition, you can apply your expanded skills in other courses, your job, and your community.

Many instructors help you develop your skills. Some prepare you by previewing a reading so you learn its background or structure. Others supply reading questions so you know what to look for or give motivational credit for reading responses. Still others may share their own reading processes with you, revealing what they read first (maybe the opening and conclusion) or how they might decide to skip a section (such as Methods in a report whose conclusions they want first).

In the end, however, making the transition to college reading requires your time and energy—and both will be well spent. Once you build your skills as a critical reader, you’ll save time by reading more effectively, and you’ll save energy by improving both your reading and your writing.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Reading Strategies

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Your Reading Strategies

Reflecting on Your Reading Strategies

Which of the methods discussed in this chapter do you use and find effective when reading textbooks, articles, and other materials for college classes? In what situations do you change your reading methods, and for what purposes? Is each of the methods you use the most effective one for your purpose? If any of the methods covered in this chapter are new to you, can you think of situations in which you might apply them? Based on your responses to these questions and further reflection, how can you improve your reading habits?

Getting Started

College reading is active reading. Your instructors expect you to do far more than recognize the words on the page. They want you to read their assignments critically and then to think and write critically about what you have read.

Your instructors will want you to learn the strategies that they and other experienced readers apply to complex texts.

Preparing to Read

Before you read, think ahead about how to make the most of the experience.

Thinking about Your Purpose. When you begin to read, ask questions like these about your immediate purpose:

What are you reading?

Why are you reading? What do you want to do with the reading?

What does your instructor expect you to learn from the reading?

Do you need to memorize details, find main points, or connect ideas?

How does this reading build on, add to, contrast with, or otherwise relate to other reading assignments in the course?

Planning Your Follow-Up. When you are required to read or to select a reading, ask yourself what your instructor expects to follow it:

Do you need to be ready to discuss the reading during class?

Will you need to mention it or analyze it during an examination?

Will you need to write about it or its topic?

Do you need to find its main points? Sum it up? Compare it? Question it? Spot its strengths and weaknesses? Draw useful details from it?

Gaining Background. Knowing a reading’s context, approach, or frame of reference can help you predict where the reading is likely to go and how it relates to other readings. Begin with your available resources:

Do the syllabus and class notes reveal why your instructor assigned the reading? What can you learn from reading questions, tips about what to watch for, or connections with other readings?

Does your reading have a book jacket or preface, an introduction or abstract that sums it up, or reading pointers or questions?

Does any enlightening biographical or professional information about the author accompany the reading?

Can you identify or speculate about the reading’s original audience based on its content, style, tone, or publication history?

Skimming the Text. Before you actively read a text, skim it—quickly read only enough to introduce yourself to it. If it has a table of contents or subheadings, read those first to figure out what it covers and how it is organized. Read the first paragraph and then the first (or first and last) sentence of each paragraph that follows. Read the captions of any visuals.

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Reading Preparation

Learning by Doing Reflecting on Reading Preparation

Reflecting on Reading Preparation

How do you approach a college reading assignment? What is your thought process when preparing to read that assignment? Consider your reason or purpose: Why are you reading? Is it to prepare for a test? To write an essay? To perform research? Write a short reflection on the most effective approach for each of these different reading situations.

Responding to Reading

You may be accustomed to reading simply for facts or main ideas. However, critical reading is far more active than fact hunting. It requires responding, questioning, and challenging as you read.

Reading Deeply. College assignments often require more concentration than other readings do. Use these questions to dive below the surface:

For more on figurative language, see the glossary in Learning from Other Writers in Ch. 13.

How does the writer begin? What does the opening paragraph or section reveal about the writer’s purpose and point? How does the writer prepare readers for what follows?

For more on evaluating what you read, see section C in the Quick Research Guide.

How might you trace the progression of ideas in the reading? How do headings, previews of what’s coming up, summaries of what’s gone before, and transitions signal the organization?

Are difficult or technical terms defined in specific ways? How might you highlight, list, or record such terms so that you master them?

How might you record or recall the details in the reading? How could you track or diagram interrelated ideas to grasp their connections?

How do word choice, tone, and style alert you to the complex purpose of a reading that is layered or indirect rather than straightforward?

Does the reading include figurative or descriptive language, references to other works, or recurring themes? How do these enrich the reading?

Can you answer any reading questions in your textbook, assignment, or syllabus? Can you restate headings in question form to create your own questions and then supply the answers? For example, change “Major Types of X” to “What are the major types of X?”

For a Critical Reading Checklist, see Reading on Literal and Analytical Levels.

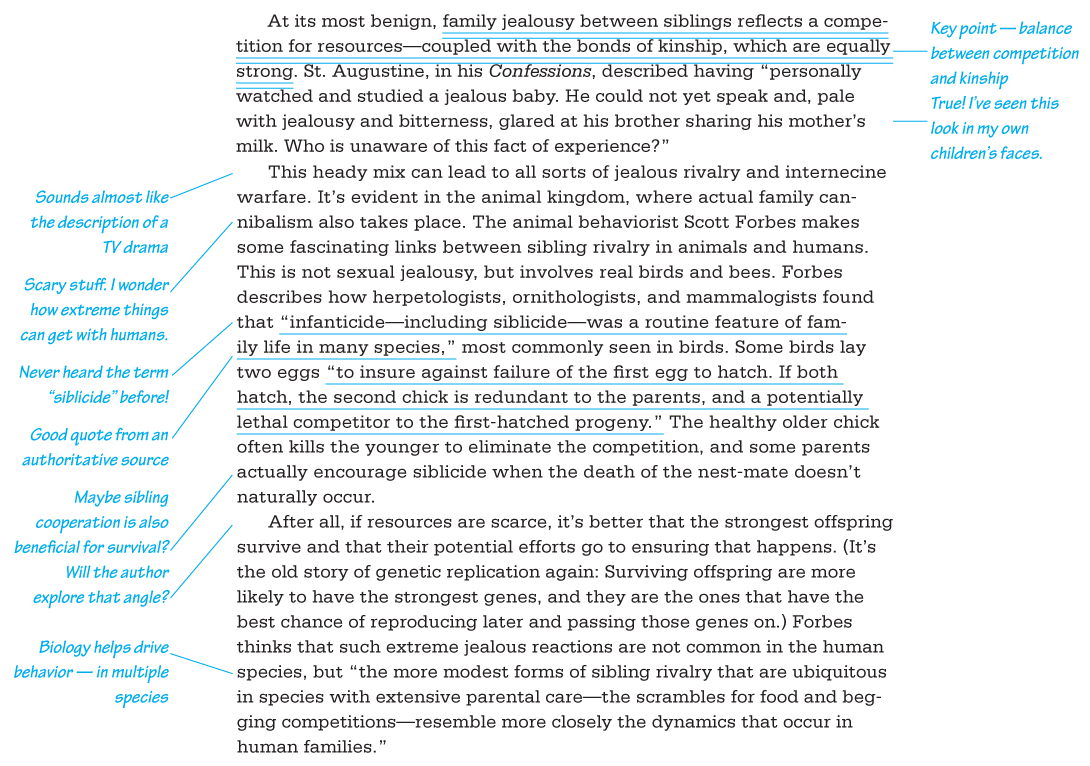

Annotating the Text. Writing notes on the page (or on a copy if the material is not your own) is a useful way to trace the author’s points, question them, and add your own comments as they pop up. The following passage is the introduction of “Sibling Rivalry, a History,” by Peter Toohey. This article was published on the Atlantic’s Web site (theatlantic.com) on November 30, 2014. Notice how one writer annotated the passage.

When you annotate a reading, don’t passively highlight big chunks of text. Instead, respond actively using pen or pencil or adding a comment to a file. Next, read slowly and carefully so that you can follow what the reading says and how it supports its point. Record your own reactions, not what you think you are supposed to say:

Jot down things you already know or have experienced to build your own connection to the reading.

Circle key words, star or check ideas when you agree or disagree, add arrows to mark connections, or underline key points, ideas, or definitions to learn the reading’s vocabulary.

Add question marks or questions about meaning or implications.

Separate main points from supporting evidence and detail. Then you can question a conclusion, or challenge the evidence that supports it. (Main points often open a section or paragraph, followed by supporting detail, but sometimes this pattern is reversed.)

React to quotable sentences or key passages. If they are hard to understand, restate them in your own words.

Talk to the writer—maybe even talk back. Challenge weak points, respond with your own thoughts, draw in other views, or boost the writer’s persuasive ideas.

Sum up the writer’s main point, supporting ideas, and notable evidence or examples.

Consider how the reading appeals to your head, heart, or conscience.

Learning by Doing Annotating a Passage

Learning by Doing Annotating a Passage

Annotating a Passage

Annotate the following passage. It opens a report titled The Evolving Role of News on Twitter and Facebook, which was published by the Pew Research Center on July 14, 2015.

1

The share of Americans for whom Twitter and Facebook serve as a source of news is continuing to rise. This rise comes primarily from more current users encountering news there rather than large increases in the user base overall, according to findings from a new survey. The report also finds that users turn to each of these prominent social networks to fulfill different types of information needs.

2

The new study, conducted by Pew Research Center in association with the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, finds that clear majorities of Twitter (63%) and Facebook users (63%) now say each platform serves as a source for news about events and issues outside the realm of friends and family. That share has increased substantially from 2013, when about half of users (52% of Twitter users, 47% of Facebook users) said they got news from the social platforms.

3

Although both social networks have the same portion of users getting news on these sites, there are significant differences in their potential news distribution strengths. The proportion of users who say they follow breaking news on Twitter, for example, is nearly twice as high as those who say they do so on Facebook (59% vs. 31%)—lending support, perhaps, to the view that Twitter’s great strength is providing as-it-happens coverage and commentary on live events.

4

These findings come at a time when the two social media platforms are increasing their emphasis on news. Twitter is soon set to unveil its long-rumored news feature, “Project Lightning.” The feature will allow anyone, whether they are a Twitter user or not, to view a feed of tweets, images and videos about live events as they happen, curated by a bevy of new employees with “newsroom experience.” And, in early 2015, Twitter purchased and launched the live video-streaming app Periscope, further highlighting their focus on providing information about live events as they happen. Meanwhile, in May, Facebook launched Instant Articles, a trial project that allows media companies to publish stories directly to the Facebook platform instead of linking to outside sites, and, in late June, Facebook started introducing its “Trending” sidebar to allow users to filter by topic and see only trending news about politics, science and technology, sports or entertainment.

5

As more social networking sites recognize and adapt to their role in the news environment, each will offer unique features for news users, and these features may foster shifts in news use. Those different uses around news features have implications for how Americans learn about the world and their communities, and for how they take part in the democratic process.

For advice on keeping a writer’s journal, see Ch. 19.

Keeping a Reading Journal. A reading journal is an excellent place to record not just what you read but how you respond to it. As you read actively, you will build a reservoir of ideas for follow-up writing. Address questions like these in a special notebook or digital file:

What is the subject of the reading? What is the writer’s stand?

What does the writer take for granted? What assumptions does he or she begin with? Where are these stated or suggested?

What are the writer’s main points? What evidence supports them?

Do you agree with what the writer has said? Do his or her ideas clash with or question your assumptions?

Has the writer told you more than you wanted to know or failed to tell you something you wish you knew?

What conclusions can you draw from the reading?

Has the reading helped you see the subject in new ways?

Learning by Doing Reflecting on a Reading Journal

Learning by Doing Reflecting on a Reading Journal

Reflecting on a Reading Journal

Consider keeping a reading journal that includes all of your research notes for a specific essay you’ve been assigned, providing commentary on each entry. Ask questions in the journal. Make observations. All your notes will be kept in one location; think about why this method could be effective for your writing process. What are the advantages of a reading journal? Can you think of any disadvantages? How might you improve your current journal-keeping strategies?