Searching the Internet

The Internet contains resources that vary greatly in quality and purpose. A quick search may turn up intriguing topic ideas or slants, but it may also turn up thousands–maybe millions–of pages of uncertain relevance and timeliness. Some of these pages are motivated by the desire to sell something. Search returns also will not necessarily be designed to meet any academic standards. And a Web search will not include the thousands of private, corporate, or government sites from the “deep” or “hidden” Web that requires passwords, limits access, or simply isn’t indexed. The sheer bulk of the information online makes searching for relevant research materials both too easy and too difficult, but a few basic principles can help.

Finding Recommended Internet Resources

For more on campus library resources, see Searching the Library.

For more on evaluating sources, see Ch. 32.

Go first to online resources recommended by your instructor or the department to which the course for which you’re conducting research belongs. Their recommendations save search time, help you avoid outdated sites, and take you directly to respected resources prepared by experts (scholars or librarians) for academic researchers (like you). Your college library, on campus or online, will offer many more resources such as those listed in the chart below.

| Resource Type | Description | Examples |

| Research Web Sites | Sponsored or maintained by libraries, academic institutions, or nonprofit consortiums. Provide reliable links grouped by subject area. |

Internet Public Library Michigan eLibrary World Wide Web Virtual Library |

| Internet Database Locators | Resources grouped by subject area (e.g., social sciences or business), topic (e.g., literary analysis), or type of information (e.g., statistics). | Auraria Library Statistics and Facts Guide |

| Government Sites | Allow specialized searches of their own collections. |

Library of Congress U.S. Census Bureau Catalog of U.S. Government Publications |

| E-book Collections | Digitized texts, including reference books and literary works, now out of copyright. |

Bartleby.com Project Gutenberg |

| Web Databases | Various public repositories with no subscription required. |

United Nations MedlinePlus |

Smart Online Searching

When you look for Internet sources on your own, you’ll want to keep your search as focused as possible to save time and retrieve the most appropriate sources.

Make the Most of Search Engines. Each online search engine has its own system of locating material, categorizing it, and establishing the sequence for reporting results. One search site, patterned on a library index, might be selective. Another might separate advertising from search results, while a third lists “sponsors” who pay advertising fees first, even though sites listed later might be better matches.

RESEARCH CHECKLIST

Evaluating Search Engines

What does the search engine’s home page suggest its typical users want–academic information, business news, sports, shopping, or music?

What does the search engine gather or index–information from and about a Web page (Bing), academic sources (Google Scholar), or a collection of other search engines (Dogpile)?

What can you learn from a search engine’s About, Search Tips, or Help?

How does the advanced search work? Does it improve your results?

Does the search engine take questions (Ask), categorize by source type (text, images, news), or group by topic (About)?

How well does the search engine target your query–the words that define your specific search?

Can you distinguish results (popular responses to your query), sponsors (advertisers who pay for priority placement), and other ads by placement, color, or other markers?

Learning by Doing Comparing Web Searches

Learning by Doing Comparing Web Searches

Comparing Web Searches

Working with some classmates, agree on the topic and terms for a test search. (Or agree to test terms each of you selects.) Have everyone conduct the same search using different search engines, and then compare results. Use the checklist above to suggest features for comparison. If possible, sit together, using your laptops or campus computers so that you can easily see, compare, and evaluate the search engine results. Report your conclusions to the class.

Conduct Advanced Electronic Searches. Search engines can access millions of records on the Internet, much as a database or library catalog accesses records on the books, periodicals, or other materials found in a library. You can search them by entering keywords into the search bar that appears on the engine’s home page.

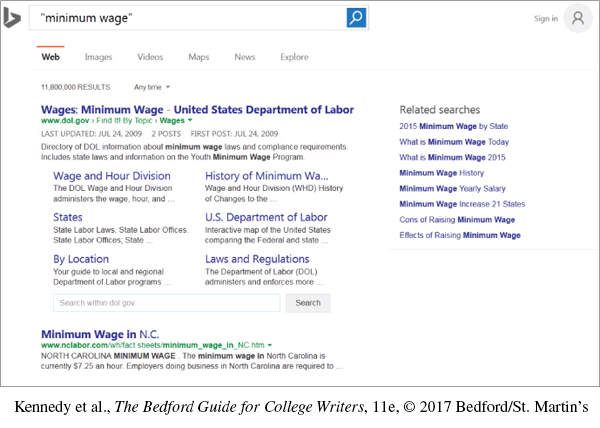

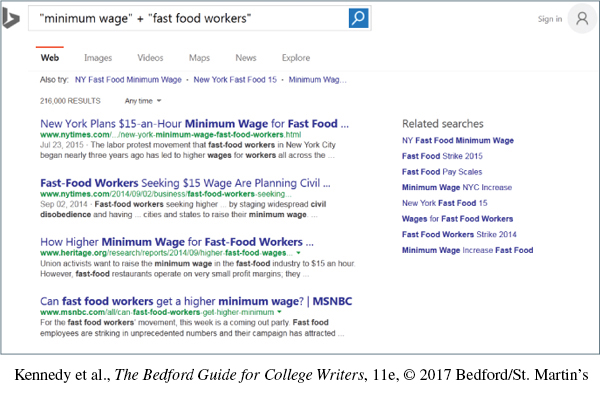

Focus the Search Terms. If the keywords you enter into a search engine are too general, you may be overwhelmed with information. For example, Figure 31.1 illustrates a search for sources on minimum wage on Bing that produced 11.8 million entries. For more relevant results, consider the aspects of the topic most necessary to your research and limit your search accordingly. As Figure 31.2 shows, a focused search (minimum wage + fast food workers) produced fewer sources on one aspect of minimum wage–fast food workers.

ABCD

ABCD

Select Limitations for Advanced Searches. Google, for example, allows you to limit searches to all, exactly, any, or none of the words you enter. Look for directions for limitations such as these:

a phrase such as elementary school safety, requested as a unit (exactly these words) or enclosed in quotation marks to mark it as a unit

a specific language (human or computer) such as English or Python

a specific format or type of software such as a PDF file

a date range (before, after, or between creation, revision, or indexing)

a domain such as .edu (educational institution), .gov (government), .org (organization), or .com (commercial site or company), which indicates the type of group sponsoring the site

a part of the world, such as North America or Africa

the location (such as the title, the URL, or the text) of the search term

the audio or visual media enhancements

the file size

For more on evaluating sources, see Ch. 32.

Find Specialized Online Materials. You can locate a variety of material online, ranging from blogs to tweets to video. For the most up-to-date news stories, use a search engine or go to the Web site for a major news outlet (e.g., the BBC, CNN, NBC, the New York Times, NPR, Reuters, or the Wall Street Journal). Be careful to distinguish expertise from opinion and speculation. Evaluate and use blogs, personal sites, and social media cautiously.