Instructor's Notes

To assign the lettered questions that appear in the exercises for this unit, go to "Browse Resources for this Unit" or to the "Resources" tab. Students can also complete the numbered exercises for practice.To assign LearningCurve adaptive quizzing activities on the topics covered in this unit, go to the LearningCurve unit that follows this one.To download handouts of the Learning by Doing activities that appear in this unit, and to access lecture slides, teaching tips, and Instructor's Manual materials, go to the "Instructor Resources" folder at the end of this unit.

22 | Appropriateness

41

Word Choice

22|Appropriateness

When you talk to people face-to-face, you can gauge their reactions to what you say. Often their responses guide your tone and your choice of words. When you write, you can’t see your readers. Instead, you must imagine yourself in their place, focusing on their responses when you revise.

Besides affecting how well you achieve your purpose as a writer, your language can affect how well you’re regarded by others. When you accurately assess the tone, formality, and word choice expected in a situation, you use the power of language to enhance your position. When you misjudge, you risk being misunderstood or judged harshly.

22aChoose a tone appropriate for your topic and audience.

Like a speaker, a writer may come across as friendly or aloof, furious or merely annoyed, playful or grimly serious. This attitude is the writer’s tone, and it strongly influences the audience’s response. For instance, readers might reject as inappropriate a humorous approach to terrorist attacks. To convey your tone, use sentence length, level of language, and vocabulary. The key is to be aware of your readers and their expectations.

22bChoose a level of formality appropriate for your tone.

Considering the tone you want to convey helps you choose words that are neither too formal nor too informal. Formal language is typically impersonal and serious. Usually written, formal language is marked by relatively complex sentences and a large vocabulary. It doesn’t use contractions (such as doesn’t).

In contrast, informal language more closely resembles ordinary conversation. It uses relatively short sentences and common words. It may include contractions, slang, and references to everyday objects and activities (cheeseburgers, T-shirts, apps). The writer may use I and address the reader as you.

The right language for most college essays lies somewhere between formal and informal. If your topic and tone are serious (say, for a research project on homelessness), then your language may lean toward formality. If your topic is not weighty and your tone is light (say, for a humorous personal essay about giving your dog a bath), then your language may be informal.

EXERCISE 22-1 Choosing an Appropriate Tone and Level of Formality

Revise the following passages to ensure that both the tone and the level of formality are appropriate for the topic and audience. Example:

I’m sending you this letter because I want you to meet with me and give me some info about the job you do.

I am writing to inquire about the possibility of an informational interview about your profession.

Dear Senator Crowley:

I think you’ve got to vote for the new environmental law, so I’m writing this letter. We’re messing up forests and wetlands—maybe for good. Let’s do something now for everybody who’s born after us.

Thanks,

Glenn Turner

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., is a great museum dedicated to a real bad time in history. It’s hard not to get bummed out by the stuff on show. Take it from me, it’s an experience you won’t forget.

Dear Elaine,

I am so pleased that you plan on attending the homecoming dance with me on Friday. It promises to be a gala event, and I am confident that we will enjoy ourselves immensely. I understand a local group by the name of Electric Bunny will provide musical entertainment. Please call me at your earliest convenience to inform me when to pick you up.

Sincerely,

Bill

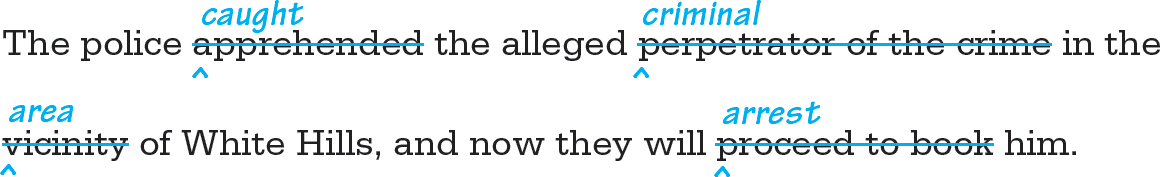

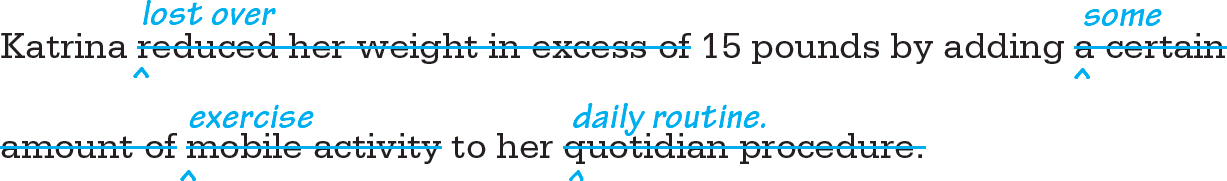

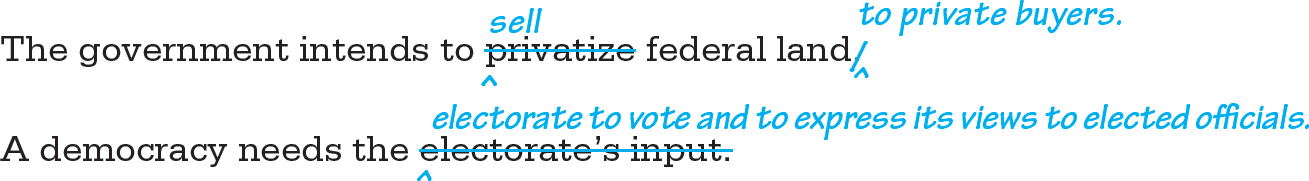

22cChoose common words instead of jargon.

Jargon is the term for the specialized vocabulary used by people in a certain field, such as music, carpentry, law, or sports. Nearly every academic, professional, and recreational field has its own jargon. To a specialist addressing other specialists, jargon is convenient and necessary. Without technical terms, after all, two surgeons could hardly discuss a patient’s anatomy. To an outsider, though, such terms may be incomprehensible. To communicate with readers without confusing them, avoid unnecessary jargon.

Jargon often results in unnecessarily wordy language because the writer is attempting to sound intellectual or to avoid speaking directly about an issue.

Many instances of jargon come from business and technical language. Avoid using technological terms such as interface and input to refer to nontechnical ideas. Also avoid ending words with the suffix -ize (as in privatize) and in the hyphenated term -wise (as in time-wise).

EXERCISE 22-2 Avoiding Jargon

Revise the following sentences to eliminate the jargon. If necessary, revise extensively. If you can’t tell what a sentence means, decide what it might mean, and rewrite it so that its meaning is clear. Example:

Everyone at Boondoggle and Gall puts in face time at the holiday gatherings to maximize networking opportunities.

This year, in excess of fifty employees were negatively impacted by Boondoggle and Gall’s decision to downsize effective September 1.

The layoffs made Jensen the sole point of responsibility for telephone interface in the customer-service department.

The numerical quotient of Jensen’s telephonic exchanges increased by a factor of three post-downsizing, yet Jensen received no additional fiscal remuneration.

Page 817Jensen was not on the same page with management re her compensation, so she exercised the option to terminate her relationship with Boondoggle and Gall.

The driver-education course prepares the student for the skills of handling a vehicle on the highway transportation system.

In the heart area, Mr. Pitt is a prime candidate-elect for intervention of a multiple bypass nature.

The deer hunter’s activity of quietizing a predetermined amount of the deer populace balances the ecological infrastructure.

22dUse euphemisms sparingly.

Euphemisms are plain truths dressed attractively, sometimes hard facts stated gently. To say that someone passed away instead of died is a common euphemism—humane, perhaps, in breaking terrible news to an anxious family. In such language, an army that retreats makes a strategic withdrawal, a person who is underweight turns slim, and an acne cream treats not pimples but blemishes.

22eAvoid slang in formal writing.

Slang, when new, can be colorful (“She’s not playing with a full deck”), playful (“He’s wicked cute!”), and apt (ice for diamonds, a stiff for a corpse). Most slang, however, quickly seems as old and wrinkled as the Jazz Age’s twenty-three skidoo! Your best bet is to stick to words that are usual but exact.

EXERCISE 22-3 Avoiding Euphemisms and Slang

Revise the following sentences to replace euphemisms with plainer words and slang with Standard English. Example:

At three hundred bucks a month, the apartment is a steal.

The soldiers were victims of friendly fire during a strategic withdrawal.

Churchill was a wicked good politician.

Saturday’s weather forecast calls for extended periods of shower activity.

The caller to the talk-radio program sounded totally wigged out.

We anticipate a downturn in economic vitality.