10.2 Constructing an Identity

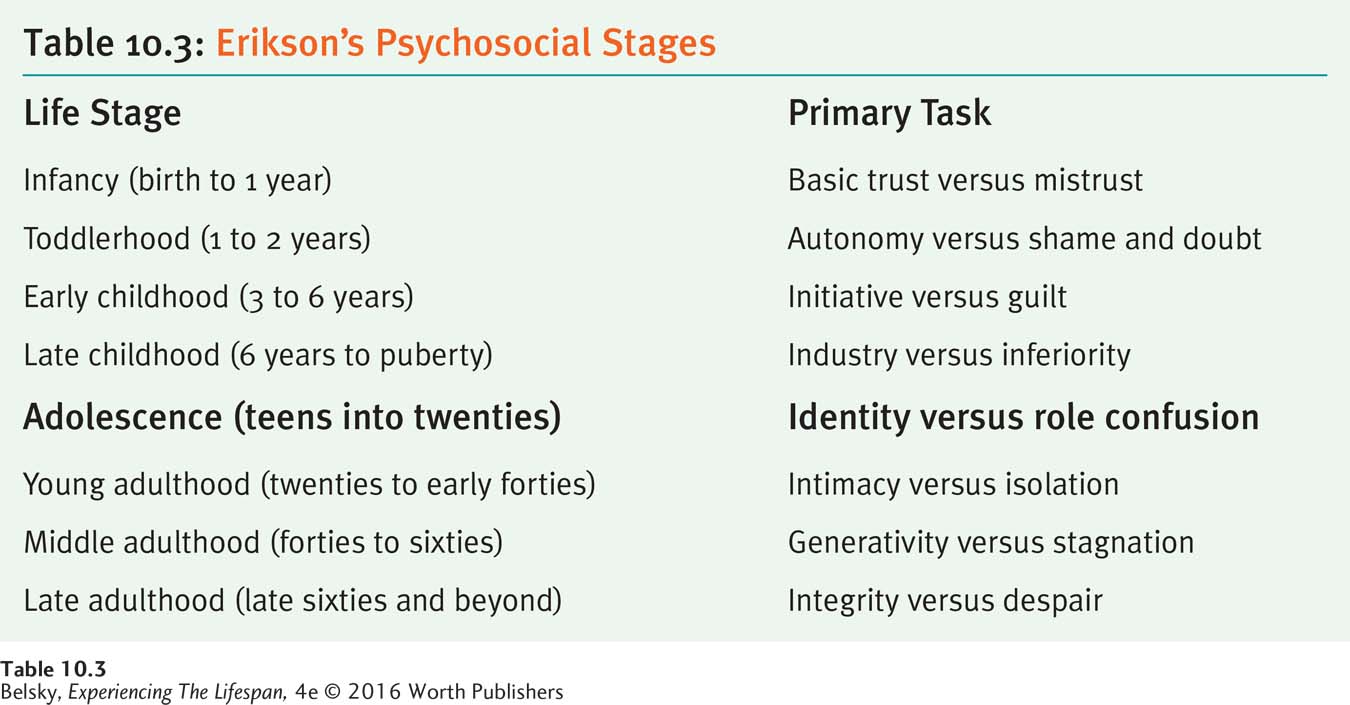

Erik Erikson was the theorist who highlighted the challenge of transforming our childhood self into the person we will be as adults. Recall he called this process the search for identity (see Table 10.3).

Time spent wandering through Europe to find himself sensitized Erikson to the difficulties young people face in constructing an adult self. Erikson’s fascination with identity as a developmental task, however, crystallized when he worked as a psychotherapist in a psychiatric hospital for troubled teens. Erikson discovered that young patients suffered from a problem he labeled role confusion. They had no sense of any adult path:

[The person feels as] if he were moving in molasses. It is hard for him to go to bed and face the transition into . . . sleep; and it is equally hard for him to get up . . . Such complaints as . . . “I don’t know” . . . “I give up” . . . “I quit” . . . are often expressions of . . . despair.

(Erikson, 1968, p. 169)

Some young people felt a frightening sense of falseness about themselves: “If I tell a girl I like her, if I make a gesture . . . this third voice is at me all the time—

This derailment, which Erikson called confusion—

Can we categorize the different ways people tackle the challenge of constructing an adult identity? Decades ago, James Marcia answered yes.

Marcia’s Identity Statuses

Marcia (1966, 1987) devised four identity statuses to expand on Erikson’s powerful ideas:

Identity diffusion best fits Erikson’s description of the most troubled teens—

young people drifting aimlessly toward adulthood without any goals: “I don’t know where I am going.” “Nothing has any appeal.”  This young woman may fit Marcia’s category of identity diffusion. She seems listless and depressed.Balazs Kovacs Images/Shutterstock

This young woman may fit Marcia’s category of identity diffusion. She seems listless and depressed.Balazs Kovacs Images/Shutterstock This student, forced by his dad to get a degree in computer science in order to get a well-

This student, forced by his dad to get a degree in computer science in order to get a well-paying job, feels incredibly bored. People who follow their parents’ career choices without exploring other possibilities are in identity foreclosure. (While Erikson and Marcia linked this status to poor mental health— as you will see on page 302— young people “in foreclosure” can also feel happy about this state.) junpinzon/Shutterstock This young woman who has accepted a company internship is in identity moratorium, because she wants to figure out if she likes working in this career. We need to know, however, if she is happily exploring her options, or unproductively obsessing about her choices.Robert Daly/Caiaimage/Getty Images

This young woman who has accepted a company internship is in identity moratorium, because she wants to figure out if she likes working in this career. We need to know, however, if she is happily exploring her options, or unproductively obsessing about her choices.Robert Daly/Caiaimage/Getty Images This delighted man is in identity achievement, because he has discovered his life passion lies in computer design.Tetra Images/Getty Images

This delighted man is in identity achievement, because he has discovered his life passion lies in computer design.Tetra Images/Getty ImagesIdentity foreclosure describes a person who adopts an identity without any self-

exploration or thought. At its violent extreme, foreclosure might apply to a Hitler Youth member or a person who becomes a terrorist in his teens. In general, however, researchers define young people as being in foreclosure when they adopt a life path handed down by some authority: “My parents want me to take over the family business, so that’s what I will do.” The person in moratorium is engaged in the exciting, healthy search for an adult self. While this internal process may provoke anxiety, because it involves wrestling with different philosophies and ideas, Marcia (and Erikson) felt it is critical to arriving at the final stage.

Identity achievement is the end point: “I’ve thought through my life. I want to be a computer artist, no matter what my family says.”

Marcia’s categories offer a marvelous framework for pinpointing what is going wrong (or right) in a young person’s life. Perhaps while reading these descriptions you were thinking, “I have a friend in diffusion. Now, I understand exactly what this person’s problem is!” How do these statuses really play out in life?

The Identity Statuses in Action

Marcia originally believed that, as we move through adolescence, we pass from diffusion to moratorium to achievement. Who thinks much about adulthood in ninth or tenth grade? At that age, your agenda is to cope with puberty. You test the limits. You sometimes act in ways that seem tailor-

However, in real life, identity pathways are erratic. People move backward and forward in statuses throughout their adult years (Côté & Bynner, 2008; Waterman, 1999). A woman might enter college exploring different faiths, then become a committed Catholic, start questioning her choice again at 30, and finally settle on her spiritual identity in Bahai at age 45. As many older students are aware, you may have gone through moratorium and firmly believed you were in identity achievement in your career, and now have shifted back to moratorium when you realized, “I need a more secure, fulfilling job.”

This lifelong shifting is appropriate. It’s unrealistic to think we reach a final identity as emerging adults. The push to rethink our lives, to change directions, to have plans and goals, is what makes us human. It is essential at any age. Moreover, revising our identity is vital to living fully since our lives are always being disrupted—

The bad news is that people can be stuck in unproductive places in their identity search. In some studies, an alarming 1 in 4 undergraduates is locked in diffusion (Côté & Bynner, 2008). They don’t have any career goals. Or, as I see in my classes, students are sampling different paths, but without much Eriksonian moratorium joy. Is your friend who keeps changing his major and putting off graduation excitedly exploring his options, or is he afraid of entering the real world? Are the emerging adults who spend their twenties moving from low-

Actually, Erikson and Marcia’s assumption that we need to sample many fields in order to construct a solid career identity, is not accurate. Having a career goal in mind from childhood, such as knowing you want to be a nurse from age nine (the status Marcia dismisses as “foreclosure”) is fine (Ryeng, Kroger, & Martinussen, 2013). Anxiously obsessing about possibilities, or being locked in a state called ruminative moratorium, causes more distress (Ritchie and others, 2013; Luyckx and others, 2014). (“I don’t know if I want to be an anesthesiologist or an actor and that’s driving me crazy.”)

There can even be problems with being identity achieved. Suppose after considerable searching you adopt a devalued identity. (“Yes, I’ll give up and go to medical school, but I’m not convinced being a doctor is really me.”) It doesn’t matter how you got there. What’s crucial is to make a commitment and feel confident that this decision expresses your true self (see Meeus, 2011; Schwartz and others, 2013 for reviews).

Ethnic Identity, a Minority Theme

The emotional pluses of committing to our identity and feeling positive about that choice are underlined by examining ethnic identity—our sense of belonging to an ethnic category, such as “Asian American.” If, like me, you are part of the mainstream culture, you rarely think of your ethnicity. For minority young people, labeling yourself as part of a group, with defined characteristics, tends to happen during concrete operations (recall Chapter 6), although the need to explore one’s relationship to that label waxes and wanes at older ages. For instance, although ethnic identity issues often become intense during the teens, one study showed that in college, people grapple with that consciousness again (Syed & Azmitia, 2009).

People cope with this consciousness in various ways. They may develop dual minority and mainstream identities (acting African American in one setting and not another), or reject one identity in favor of another (“I never think of myself as Black, just as American,” or “I never think of myself as American, just as Black”) (Phinney, 2006).

Studies routinely show that identifying with one’s ethnicity is correlated with a host of positive attributes and traits (Acevedo-

The challenges for biracial or multiracial emerging adults, people from mixed racial or ethnic backgrounds (like President Obama), are particularly poignant. These young people may feel adrift without any ethnic home (Literte, 2010). But, here, too, reaching identity achievement can have widespread benefits. Fascinating research suggests having a biracial or bicultural background pushes people to think in more creative, complex ways about life (Tadmor, Tetlock, & Peng, 2009). It can promote resilience, too. As one biracial woman in her early thirties put it: “When I was younger I felt I didn’t belong anywhere. But now I’ve just come to the conclusion that my home is inside myself” (Phinney, 2006, p. 128).

Making sense of one’s “place in the world” as an ethnic minority is literally a minority identity theme. But every young person has to grapple with those two universal identity issues: choosing a career and finding love. The rest of this chapter tackles those agendas.

Tying It All Together

Question 10.5

You overheard your psychology professor saying that his daughter Emma shows symptoms of Erikson’s identity confusion. Emma must be ______ (drifting, actively searching for an identity), which in Marcia’s identity status framework is a sign of ______ (diffusion, foreclosure, moratorium).

drifting; diffusion

Question 10.6

Joe said, “I’ve wanted to be a lawyer since I was a little boy.” Kayla replied, “I don’t know what my career will be, and I’ve been obsessing about the possibilities day and night.” Joe’s identity status is ______ (moratorium, foreclosure, diffusion, or achievement), while Kayla’s status is ______ (moratorium, foreclosure, diffusion, or achievement). According to the latest research, who is apt to be most anxious and disturbed?

foreclosure; moratorium. Kayla is most likely to be distressed (in moratorium).

Question 10.7

Your cousin Clara has enrolled in nursing school. To predict her feelings about this decision, pick the correct question to ask: Have you explored different possibilities?/Do you feel nursing expresses your inner self ?

Do you feel nursing expresses your inner self?

Question 10.8

Confronting the challenge of a biracial or multiracial identity tends to make people think in more rigid ways about the world. (True or False)

False