10.3 Finding a Career

In a famous statement, Sigmund Freud, when asked to sum up the definition of ideal mental health, answered with the simple words, “the ability to love and work.” Let’s now look at finding ourselves in the world of work.

When did you begin thinking about your career? What influences are drawing you to psychology, nursing, or business—

To answer these kinds of questions, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Barbara Schneider (2000) conducted a pioneering study of teenagers’ career dreams. They selected 33 U.S. schools and interviewed students from sixth to twelfth grade. To chart how young people felt—

Entering with High (but Often Unrealistic) Career Goals

Almost every teenager, the researchers found, expects to go to college. Almost everyone wants to have a professional career. The tendency to aim high appears regardless of gender or social class. Whether male or female, rich or poor, adolescents have lofty career goals. Moreover, I believe that the experts who view today’s young people as over coddled (Levine & Dean, 2012), narcissistic (Twenge, 2006), and “basically” unmotivated are unfair. Due to the lingering effects of the Great Recession, young people face a far harsher economic climate than we baby boomers encountered when we emerged into adult life (Economic Policy Institute, n.d.). In one survey of U.S. college freshmen, young people reported being more driven to work hard than their counterparts in previous years (Pryor and others, 2011).

The real problem, however, is that teens are (naturally) clueless about what it takes to implement their dream careers. Can someone who “hates reading” really spend a decade getting a psychology Ph.D.? What happens when my students learn they have to have a GPA close to 3.7 to enter our university’s nursing program, or they can’t go to law school because of the astronomical costs? Career disappointment can lurk right around the corner for young people as they emerge from the cocoon of high school and confront the real world. How do people react as they enter their college years?

Self-Esteem and Emotional Growth During College and Beyond

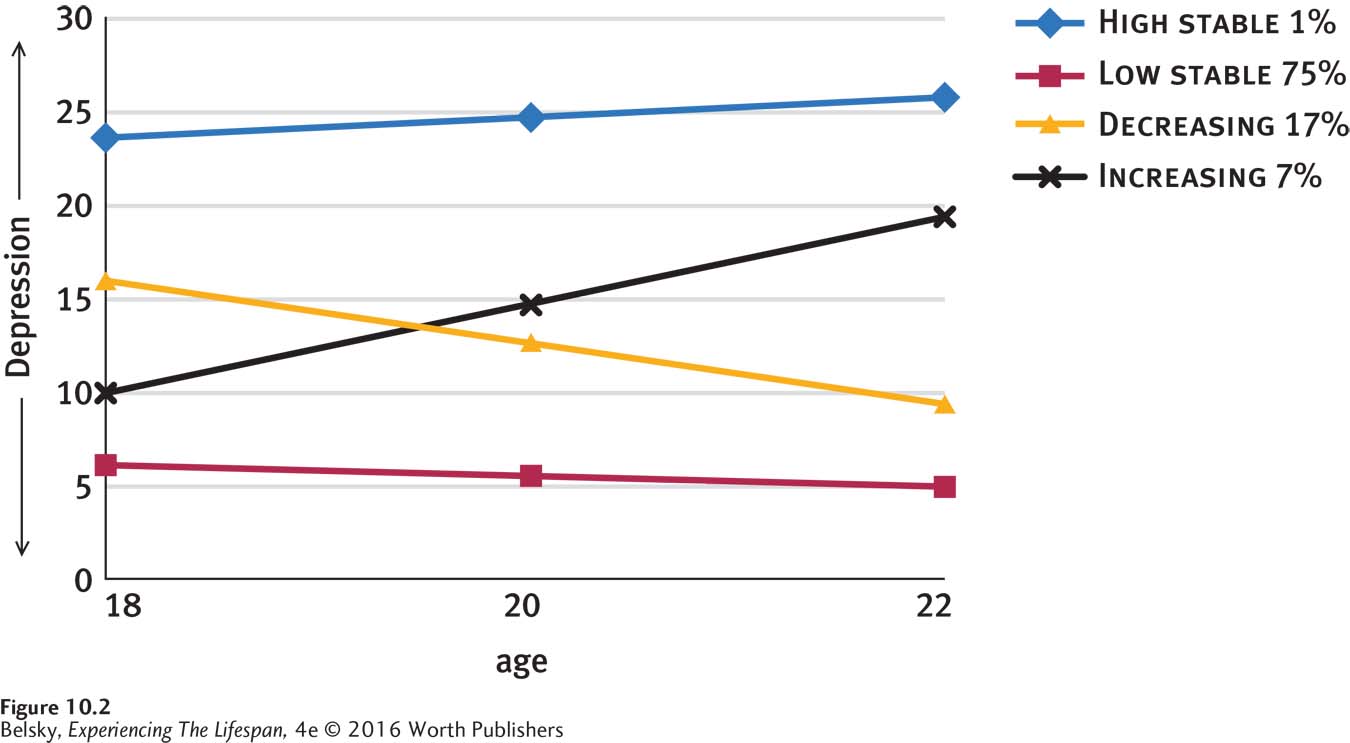

Interestingly, one U.S. survey showed that self-

Who thrives? The figure implies that personality matters. Young people who enter emerging adulthood upbeat and competent are set up to flourish when confronting the demands of college life. In their study, Csikszentmihalyi and Schneider (2000) called these efficacious teens “workers”—the 16-

You might think finding love would be especially important for females. You would be wrong. Interestingly, men, in particular, felt especially good about themselves if they were in a caring relationship by age 23 (Wagner and others, 2013).

In what ways do people change for the better during this landmark decade? Growth is most apt to occur in a temperamental dimension that researchers call conscientiousness—

To explain this rise in executive functions—

Finding Flow

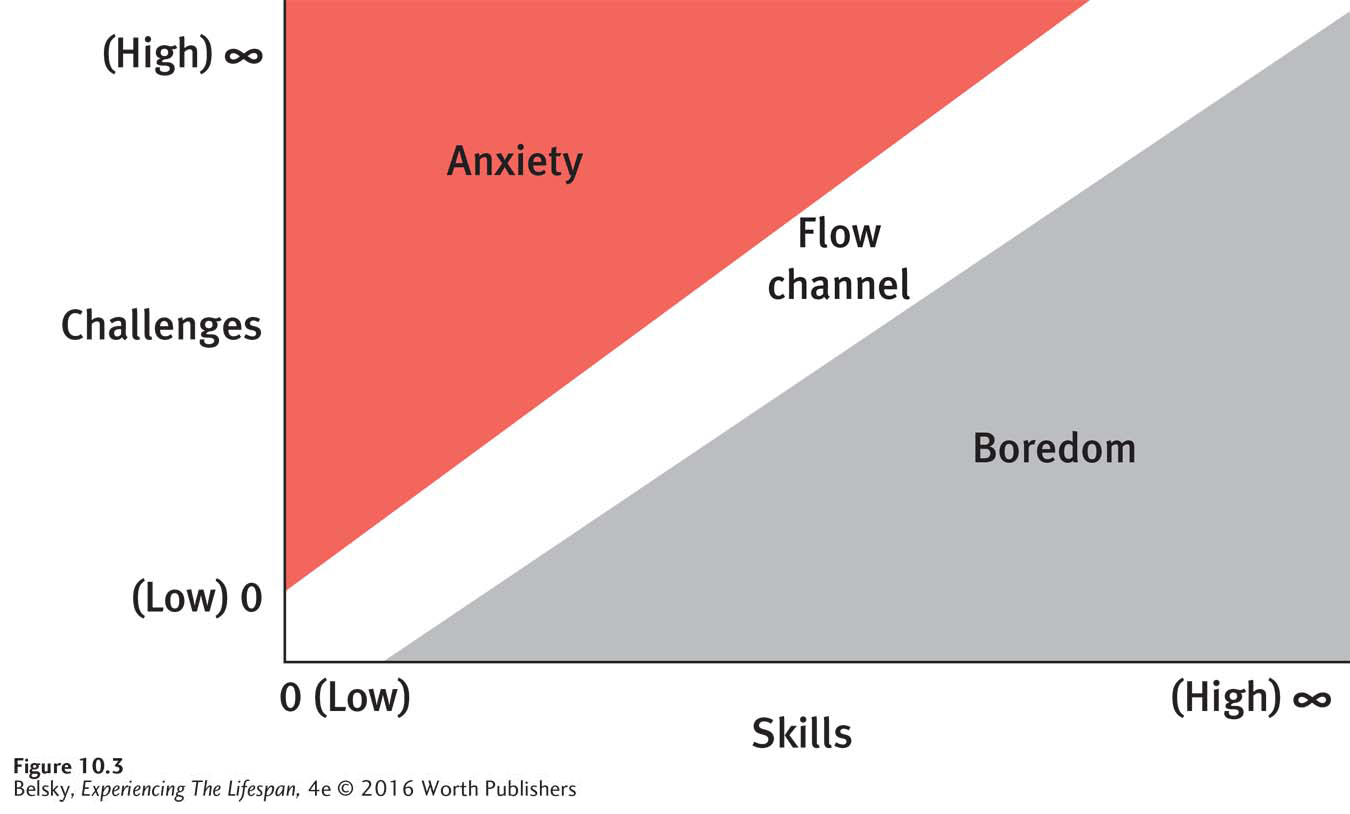

Think back over the past week to the times you felt energized and alive. You might be surprised to discover that events you looked forward to—

Flow is different from “feeling happy.” We enter this state when we are immersed in an activity that stretches our capacities, such as the challenge of decoding a difficult academic problem, or (hopefully) getting absorbed in mastering the material in this class. People also differ in the kinds of activities that cause flow. For some of us, it’s hiking in the Himalayas that produces this feeling. For me, it has been writing this book. When we are in flow, we enter an altered state of consciousness in which we forget the outside world. Problems disappear. We lose a sense of time. The activity feels infinitely worth doing for its own sake. Flow makes us feel completely alive.

Csikszentmihalyi (1990), who has spent his career studying flow, finds that some people rarely experience this feeling. Others feel flow several times a day. If you feel flow only during a rare mountain-

Flow depends on being intrinsically motivated. We must be mesmerized by what we are doing right now for its own sake, not for an extrinsic reward. But there also is a future-

For example, the idea that this book will be published two years from now is the goal that is pushing me to write this very page. But what riveted me to my chair this morning is the actual process of writing. Getting into a flow state is often elusive. On the days when I can’t construct a paragraph, I get anxious. But if I could not regularly find flow in my writing, I would never be writing this book.

Figure 10.3 shows exactly why finding flow can be difficult. That state depends on a delicate person–

Vygostky

Drawing on the concept of flow, my discussion of identity, as well as recent economic concerns, let’s now look at two career paths emerging adults in the United States follow.

Emerging into Adulthood Without a College Degree (in the United States)

“I never want this kind of job for my kids.” This comment, from a 35-

People in the United States who don’t go to college or who never get their degree can have fulfilling careers. Some may excel at Robert Sternberg’s practical or creative intelligence (described in Chapter 7) but do not do well at academics. When they find their flow in the work world, they blossom. Consider the career of that college failure, the famous filmmaker named Woody Allen, or even that of Bill Gates, who found his undergraduate courses too confining and left Harvard to pioneer a new field.

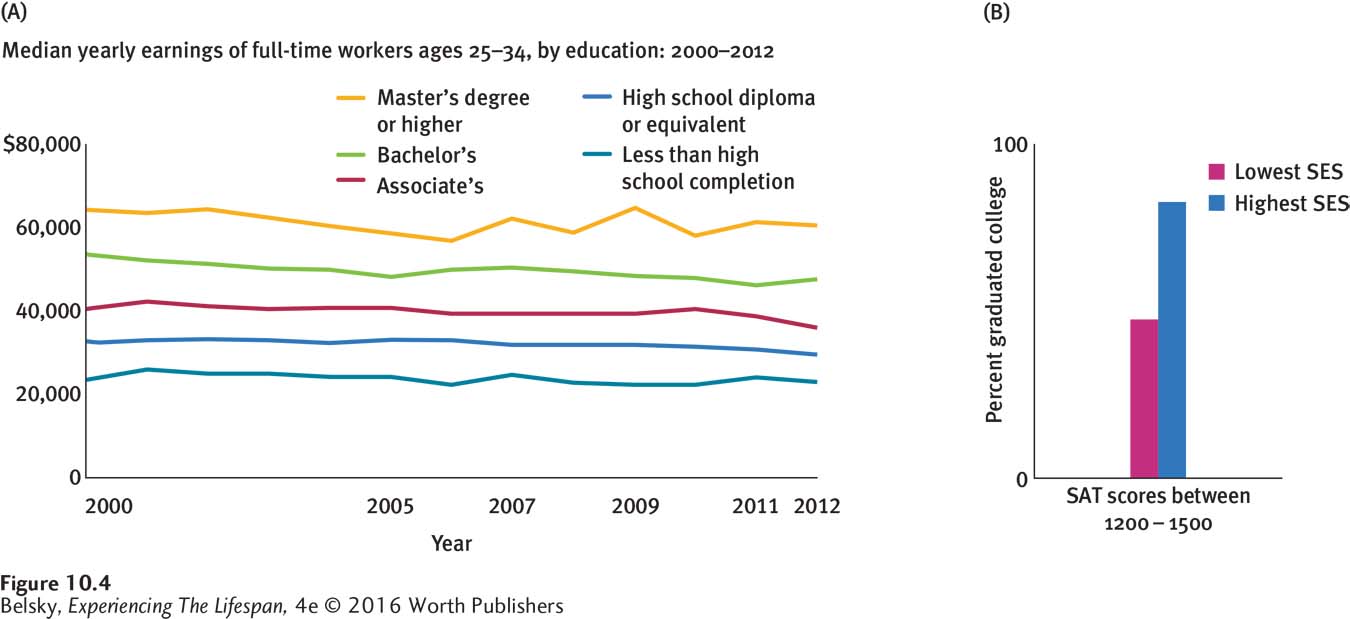

Unfortunately, these famous college dropouts are a statistical blip. The bleak reality is that non-

Given these realities, why do many emerging adults drop out of school? Our first assumption is that most of these people are not “college material”—uninterested in academics, poorly prepared in high school, and/or can’t do the work.

True, to succeed in college, prior academic aptitude is important. As a C student in your public school class, your odds of getting a bachelor’s degree are less than 1 in 5 (Engle, n.d.). But, as Figure 10.4B shows, economic considerations matter greatly. The unfortunate reality is that talented, low-

When the Gates Foundation commissioned a survey of more than 600 young adults ages 22 to 30 who had dropped out of college, they discovered the same message—

The silver lining is that most of these people did plan to return. And, as many nontraditional student readers are aware, there can be emotional advantages to leaving and then coming back. In Sweden, the social clock for college is programmed to start ticking a few years after high school (Arnett, 2007). The reasoning is that time spent in the wider world helps people home in on what to study in school.

Moreover, as you saw in the beginning chapter vignette, emerging adults can sometimes advance in their careers without a college degree. Employers look for reliability and a good work ethic, virtues that can be demonstrated once someone gets his foot in the door. When British researchers explored the qualities that distinguished people who left school at l6 and had gone on to do well economically during midlife (granted, during better economies), the main predictor that stood out was prior academic skills (Schoon & Duckworth, 2010). So, if a non-

INTERVENTIONS: Smoothing the School Path and School-to-Work Transition

Still, we can’t let society off of the hook. The fact that financing college is difficult for U.S. young people is a national shame. The standard practice of taking out loans means that young people face frightening economic futures after getting their degrees. In 2012, more than half of U.S. emerging adults left college owing the government and private lenders $20,000 or more. Moreover, in the same poll, more than 1 out of 2 graduating seniors searching for a full-

What can colleges do? Rather than having students languish, unproductively shifting from major to major, offer centralized advising to get students on the right track during the freshman year (Kot, 2014). As of this writing, states are experimenting with low-

Most important, we need to rethink our contemporary emphasis on college as the only ticket to a decent life. As some people are skilled at working with their hands, or excel in practical intelligence, why force non-

Germany, like other Western countries, has a youth unemployment problem. But because its apprenticeship programs offer young people careers outside of college, this nation helps undercut the unproductive ruminative-

How many young people are locked in diffusion or moratorium because the United States lacks a defined school-

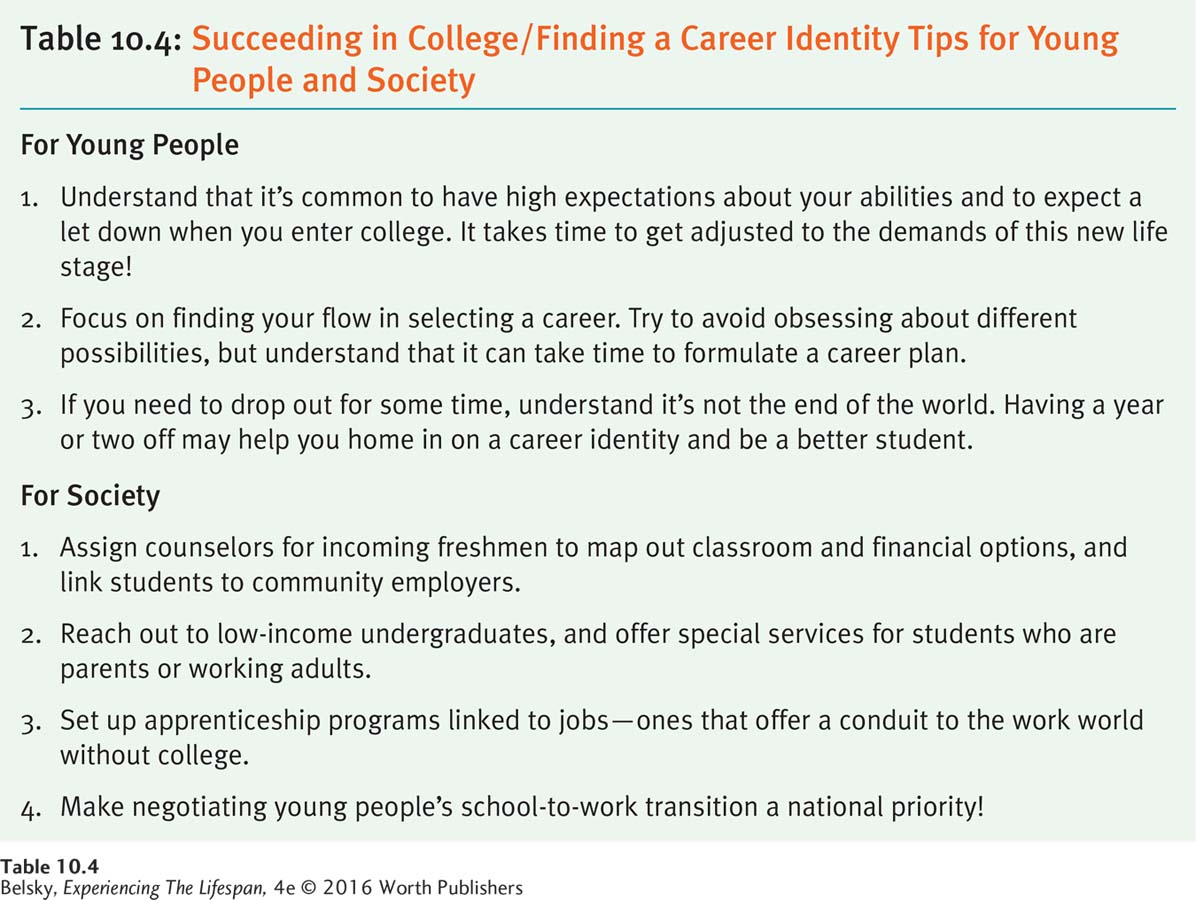

Table 10.4 summarizes the main messages of this section, by offering suggestions for emerging adults and society at large. Now, it’s time to immerse ourselves in the undergraduate experience.

Being in College

So far, I’ve been implying that the only purpose of going to college is to find a career. Thankfully, in surveys, most U.S. college graduates disagree. They report the main value of their undergraduate years was to help them “grow intellectually and personally” (Hoover, 2011).

How does this inner growth progress during college? According to William Perry (1999), freshmen come in blindly accepting the facts that authorities hand down, and then they move to relativism (understanding that there are multiple truths); by senior year, they make their own ethical commitments in the face of appreciating diverse points of view.

Perry’s findings are based on studies conducted with Harvard undergraduates 40 years ago. But another longitudinal study (granted, also at a selective university) confirms that this inner development occurs—

If you are a traditional college student, here are tips to make your college experience an inner-

INTERVENTIONS: Making College an Inner-Growth Flow Zone

GET THE BEST PROFESSORS (AND TALK TO THEM OUTSIDE OF CLASS!). It’s a no-

From a Harvard senior:

He began by asking me which single book had the biggest impact on me. He was the first professor who was interested in what matters to me. . . . You can’t imagine how excited I was.

(quoted in Light, 2001, pp. 82–

From a community college student:

You know, what he does more than anything else is that . . . he really listens. I was in his office last semester and I was telling him how I was struggling. . . . He really let me talk myself into doing what I needed to pass. It’s like, you know he gives a damn.

(quoted in Schreiner and others, 2011, p. 324)

CONNECT YOUR CLASSES TO POTENTIAL CAREERS. Professors’ mission is to excite you in their field. But classes can’t provide the hands-

IMMERSE YOURSELF IN THE COLLEGE MILIEU. Following this advice is easier if you are attending a small residential school. The college experience is at your doorstep, ready to be embraced. At a large university, especially a commuter school, you’ll need to make efforts to get involved in campus life. If possible, spend your first year living in a college dormitory. Join a college organization, or two, or three. Working for the college newspaper or becoming active in the drama club not only will provide you with a rich source of friends, but can help promote your career identity, too.

CAPITALIZE ON THE DIVERSE HUMAN CONNECTIONS COLLEGE PROVIDES. As you saw in previous chapters, the peer groups we select help shape who we become. At college, it is tempting to find a single clique and then not reach out to other crowds. Resist this impulse. A major growth experience college provides is the chance to connect with people of different points of view (Hu & Kuh, 2003; see also Leung & Chiu, 2011). Here’s what another Harvard undergraduate had to say:

I have re-

(quoted in Light, 2001, p. 163)

But this community college student summed it up best:

When I come home and have all these great stories; they think college is the most amazing thing . . . and that’s because of all the people I’m surrounded with.

(quoted in Schreiner and others, 2011, p. 337)

Being surrounded by interesting people has another benefit: It smoothes the way to Erikson’s other emerging adult task: finding love.

Tying It All Together

Question 10.9

Your 17-

Overly high

Question 10.10

Juan has just turned 19; all of these forces predict he may have high self-

Juan is a “worker,” a person who thrives on mastering challenging tasks.

Juan gets good college grades.

Juan puts off having a close love relationship during these years.

c. Juan might do best if he finds a close caring relationship during these years

Question 10.11

Hannah confesses that she loves her server job—

flow

Question 10.12

Josiah says the reason why his classmates drop out of college is that they can’t do the work. Jocasta says, “Sorry, it’s the need to work incredible hours to pay for school.” Make each person’s case, using the information from this chapter.

Josiah might argue that prior academic performance predicts college completion, with low odds of finishing for high school graduates with a C-

Question 10.13

Your cousin Juan, who is about to enter his freshman year, asks you for tips about how to succeed in college. Based on the information in this section, pick the advice you should not give:

Get involved in campus activities.

Search out friends who have exactly the same ideas as you do.

Select the best professors and reach out to make connections with them.

b