10.4 Finding Love

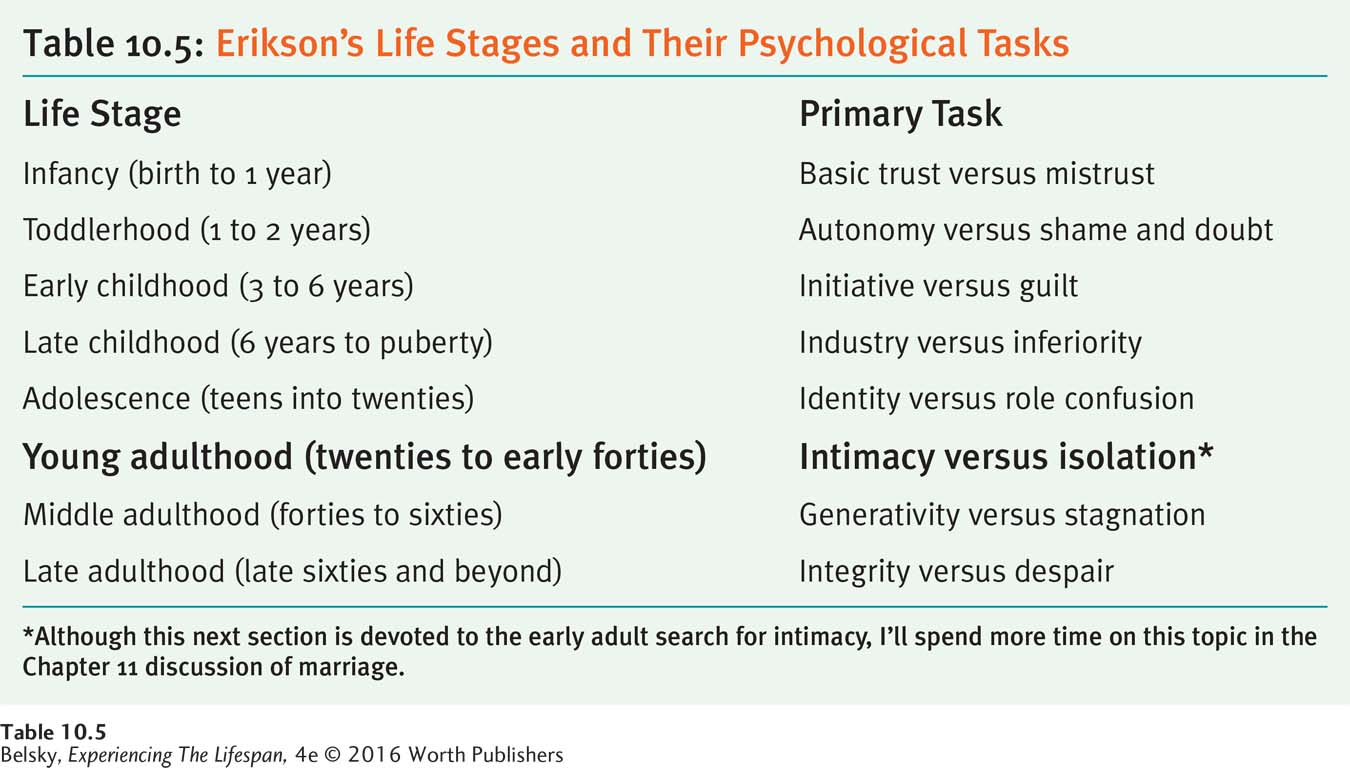

How do emerging adults negotiate Erikson’s first task of adult life (see Table 10.5)—intimacy, the search for love? Let’s first explore two major cultural shifts in the ways we choose mates before turning to our main topic: finding fulfilling love.

Setting the Context: Seismic Shifts in Searching for Love

The following quotations perfectly introduce our first total transformation in how we search for enduring love:

Daolin Yang lives in Hebie Province, China. . . . At age 15, he married his wife Yufen, then 13. . . . A matchmaker proposed the marriage on behalf of the Yang family. They have been married for 62 years. . . . He says that they married first and dated later. It is “cold at the start and hot in the end.” The relationship gets better and better over the years.

(Xia & Zhou, 2003, p. 231)

I got married a month ago to the woman . . . I met on Match a year ago. I met my wife just a week after setting up my profile, and we have been together ever since . . . Thanks to the profiles, local singles matching, and easy chats, I found the girl of my dreams.

(Adapted from, Top 10 Best Dating Sites, 2014)

Many More Potential Partners

Throughout history, as I just illustrated in the first example, in many regions of the world, parents chose a child’s marital partner (often during puberty), and newlyweds hoped (if they were lucky) to later fall in love. Today, even in places like India, where, until recently, arranged marriages had been standard, many people accept freely choosing a mate (Gala & Kapadia, 2014, more about this topic in the next chapter).

Moreover, until very recently, romantic choices were confined to our own social network. People searched for their soul mates at parties, at school, or at synagogue. Often, they relied on family and friends to fix them up.

Today, with the explosion of on line dating, as we all know, the Internet has globalized the search for love. By the second decade of the twentieth century, an incredible 1 in 3 married couples in the United States had met on-

At the same time, since the 1960s lifestyle revolution, Western young people are far more willing to date outside of their own ethnic group. By the turn of the twenty-

Interest in dating and/or marrying outside one’s own ethnicity varies from person to person. In one survey of on-

Religious attitudes also make a difference. Contrary to popular opinion, one national U.S. poll found that having a strong religious faith might not matter. But if someone is White and accepts the bible as literal truth (and doesn’t attend a multiracial congregation), this person is apt to be more opposed to this widening of love choices (Perry, 2013).

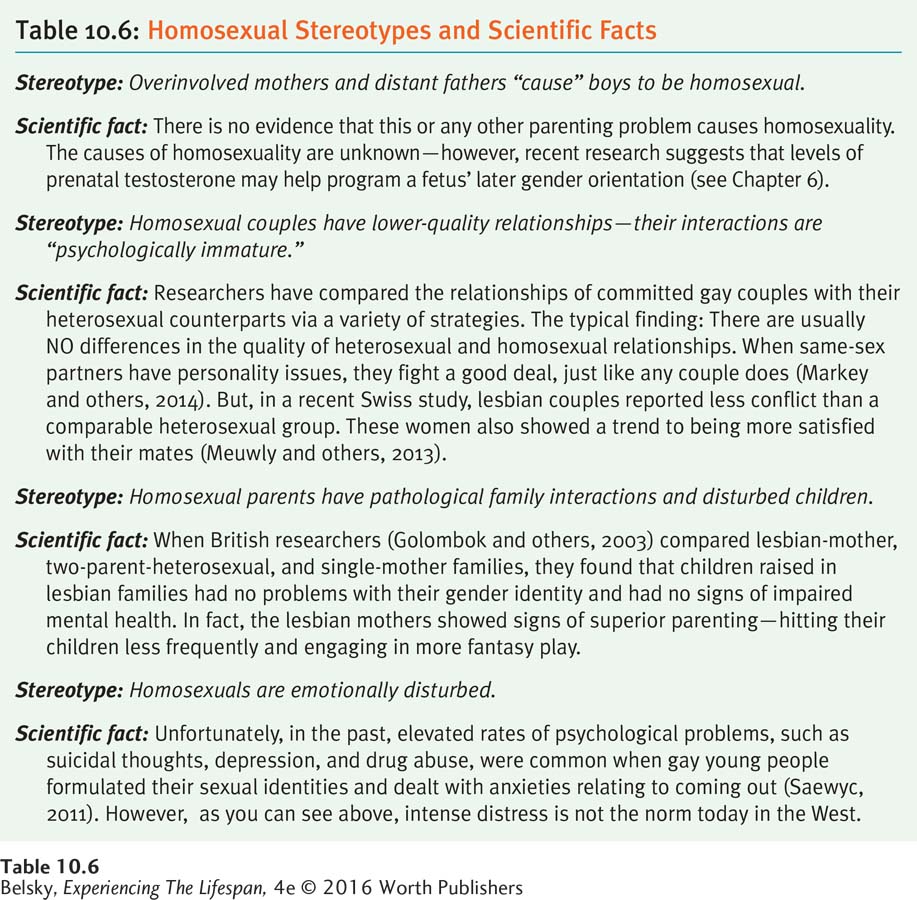

Christians who believe biblical injunctions must be obeyed word for word are particularly aghast (no surprise!) at that other contemporary expansion in the landscape of love: same-

Hot in Developmental Science: Same-Sex Romance

In the 1990s, when I began teaching at my southern university, I remember being disturbed by the snickering that would erupt when I mentioned issues related to being gay. No more! Although the gay rights movement exploded on the scene in the late 1960s in New York City, its most revolutionary strides took place during the early twenty-

This is not to say that homophobia, fear and dislike of gays and lesbians, is rare. Despite our landmark U.S. strides in legalizing same sex marriage in all 50 states—

Given this continuing (although more covert) social scorn, it makes sense that sexual-

Another at-

Again, I think this research underlines the importance of being identity achieved in a positive way. Once you embrace your identity (or self), whether as a gay person or ethnic minority, there is a feeling of self-

A More Erratic, Extended Dating Phase

Unfortunately, however, as I implied earlier in this chapter, romantic moratorium is built into Western society because the untethered dating phase of mate selection lasts so long (Shulman & Connolly, 2013). As the average age of marriage has shifted upward, people not only are delaying making serious love commitments, but younger emerging adults are even putting off getting romantically involved.

In tracking over 500 economically diverse young people from age 18 to 25, U.S. researchers found a fraction—

When emerging adults do find romance, they may have off-

This extended finding-

What happens when young people delay making love commitments? We might think that having casual sexual encounters is a risk-

At the risk of going out on a limb (your class can debate this point), I’m going to agree with Erikson that finding intimacy—

Similarity and Structured Relationship Stages: A Classic Model of Love, and a Critique

Bernard Murstein’s now-

When we start actually dating, we enter the value-

So, at a party, Aaron scans the room and decides that Samantha with the tattoos and frumpy-

The “equal-

Most important, Murstein’s theory suggests that opposites do not attract. In love relationships, as in childhood and adolescent friendships, the driving force is homogamy (similarity). We want to find a soul mate, a person who matches us, not just in external status, but also in interests and attitudes about life.

The principle that homogamy promotes happiness (the eHarmony, Match, and Christian Mingle approaches to love) has scientific truth. Late-

The Limits to Looking for a Similar Mate

But should couples be similar in every respect? When psychologists asked undergraduates to describe their ideal mate, in accordance with the homogamy principle, people selected someone with a similar personality. But, in actually examining happiness among long-

Logically, matching up two strong personalities should be unlikely to promote romantic bliss (people would probably fight). Two passive partners might frustrate each other. (“Why doesn’t my lover take the lead?”) Yes, in general, similarity is important. (Birds of a feather should flock together!) But, as in the other familiar saying, “opposites attract,” couples can mesh best when they have a few carefully selected opposing personality preferences and styles.

Moreover, suppose a given couple is very similar but in unpleasant traits, such as their tendency to fly off the handle or be pathologically shy. What really matters in happiness is not so much objective similarity (the eHarmony approach of matching people whose personality test scores agree), but believing that one’s significant other has terrific personality traits. People who see their partner as outgoing and emotionally stable (“He is a real people person, and open to new things”) have better relationships over time (Furler, Gomez, & Grob, 2013; Furler, Gomez, & Grob, 2014).

The bottom-

Actually rather than “objectively” matching up, happy couples see their mates through rose-

The Limits to Charting Love in Stages

As soon as I met R, . . . he was just so kind and thoughtful and he was considerate. So we started talking on email and the phone and when I got back from the trip, and he came over a month after the cruise . . . I knew like right away . . . It was just like kind of a confirmation that, I don’t know, we were meant to be together.

(quoted in Mackinnon and others, 2011, p. 607)

This quotation implies that, by viewing mate selection in defined steps, Murstein is also missing the magical essence of real-

While turbulent relationships can spark passion, especially for men (that’s the thrill of the chase), one study found that married couples who recalled their courtship as accelerating in a positive direction were more likely to report being happy with their mates (Wilson & Huston, 2013). Happily married spouses, it turned out, recalled having similar levels of love as their relationship developed. They were on the same page about how their feelings progressed. Still, even though we should become surer of our love over time, any romance has some doubts and ups and downs.

To get insights into this ebb and flow, researchers asked couples who were seriously dating to graph their chances (from 0 to 100 percent) of marrying their partner (Surra & Hughes, 1997; Surra, Hughes, & Jacquet, 1999). They then had the young people return each month to chart changes in their commitment and asked them to describe the reasons for any dramatic relationship turning points, for better or worse.

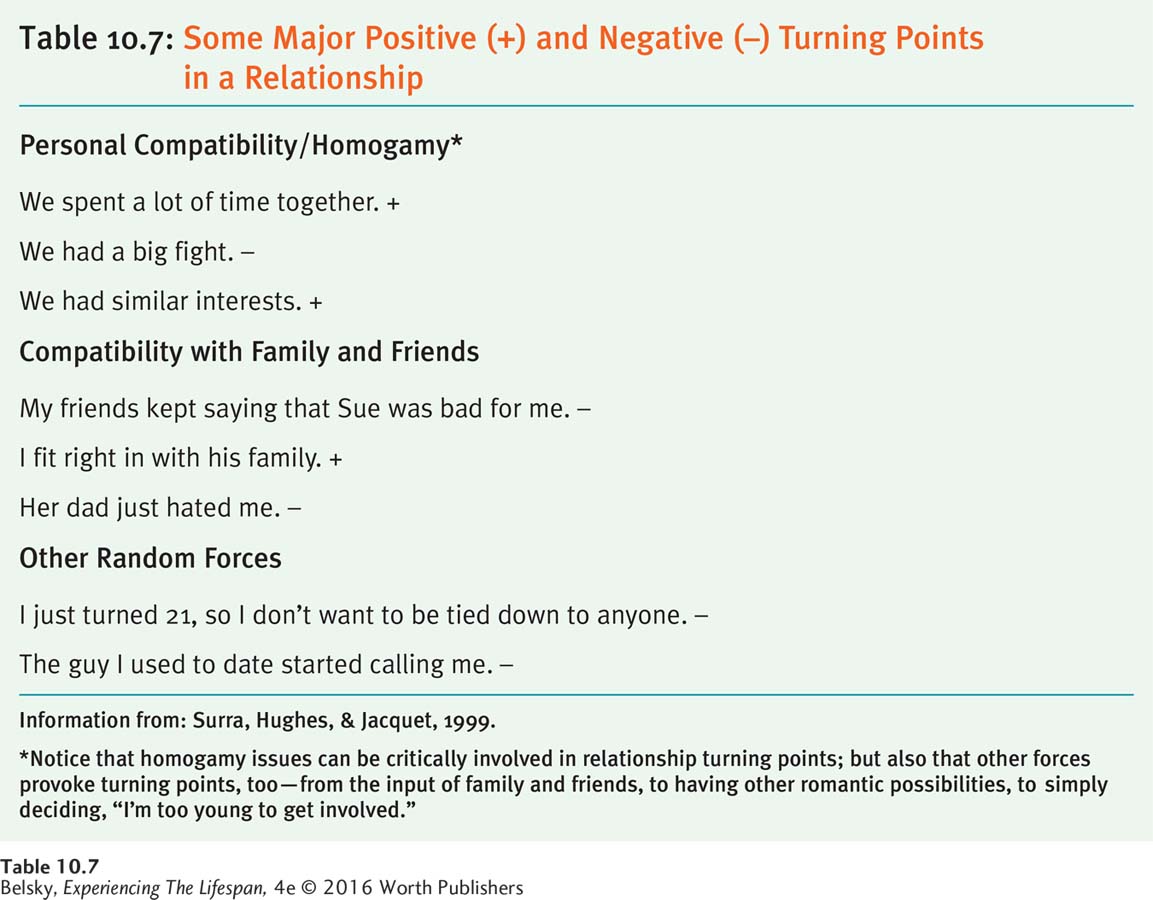

You can see examples of these turning points in Table 10.7. Notice that relationships do often hinge on homogamy issues (“This person is really right for me”). Other causes may be turning points, too—

Hot in Developmental Science: Facebook Romance

Facebook is a double-

In one focus-

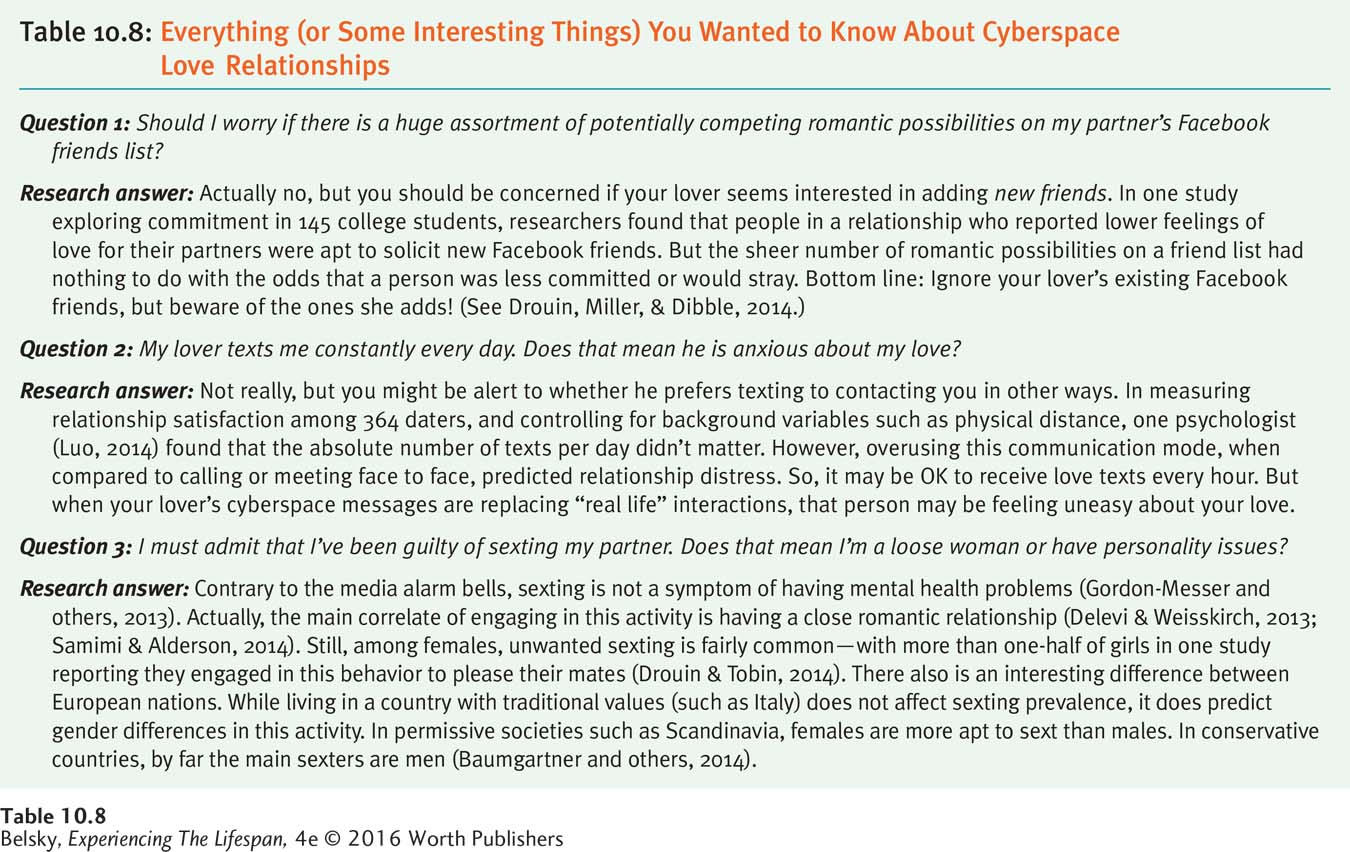

The universal perception of the young people in this study, however, was that, in their words: “Facebook is a trap”; “It’s a total . . . train wreck”; “It’s not going to make a relationship better but it could make it worse” (quoted in Fox, Osborn, & Warber, 2014, p. 531). Unfortunately, however, everyone still felt wedded to this technology. In spite of reporting numerous negative experiences, 46 of these 47 young adults still maintained a Facebook page. The one emerging adult who had deleted his profile was reconsidering getting a new one, ironically, “just to keep tabs on his girlfriend” (p. 533). (Check out Table 10.8 for other interesting research facts related to romance in the on-

Although it makes romance (in Facebook terms) “complicated,” the on-

Love Through the Lens of Attachment Theory

Think back to Chapter 4’s discussion of the different infant attachment styles. Remember that Mary Ainsworth (1973) found that securely attached babies run to Mom with hugs and kisses when she appears in the room. Avoidant infants act cold, aloof, and indifferent in the Strange Situation when the caregiver returns. Anxious-

People with a preoccupied/ambivalent type of insecure attachment fall quickly and deeply in love (see the How Do We Know box). But, because they are engulfing and needy, they often end up being rejected or feeling chronically unfulfilled. Adults with an avoidant/dismissive form of insecure attachment are at the opposite end of the spectrum—

HOW DO WE KNOW . . .

that a person is securely or insecurely attached?

How do developmentalists classify adults as either securely or insecurely attached? In the current relationship interview, they ask people questions about their goals and feelings about their romantic relationships; for example, “What happens when either of you is in trouble? Can you rely on each other to be there emotionally?” Trained evaluators then code the responses.

People are labeled securely attached if they coherently describe the pluses and minuses of their own behavior and of the relationship, if they talk freely about their desire for intimacy, and if they adopt an other-

This in-

Secure attachment

Definition: Capable of genuine intimacy in relationships.

Signs: Empathic, sensitive, able to reach out emotionally. Balances own needs with those of partner. Has affectionate, caring interactions. Probably in a loving, long-

term relationship.

Avoidant/dismissive insecure attachment

Definition: Unable to get close in relationships.

Signs: Uncaring, aloof, emotionally distant. Unresponsive to loving feelings. Abruptly disengages at signs of involvement. Unlikely to be in a long-

term relationship.

Preoccupied/ambivalent insecure attachment

Definition: Needy and engulfing in relationships.

Signs: Excessively jealous, suffocating. Needs continual reassurance of being totally loved. Unlikely to be in a loving, long-

term relationship.

Securely attached people are fully open to love. They give their partners space to differentiate, yet are firmly committed. Like Ainsworth’s secure infants, their faces light up when they talk about their partner. Their joy in their love shines through. Decades of studies exploring these different attachment styles show that insecurely attached adults have trouble with relationships. Securely attached people are more successful in the world of love.

Securely attached adults have happier marriages. They report more satisfying romances (Feeney, 1999; Mikulincer and others, 2002; Morgan & Shaver, 1999). Avoidant husbands are disengaged when their wives get upset (Barry & Lawrence, 2013). Perhaps because they are so frightened about being left, anxiously attached spouses are more apt to have affairs (Russell, Baker, & McNulty, 2013). Insecurely attached people get far more dissatisfied with their lovers over time (Hadden, Smith, & Webster, 2014). But, securely attached adults hang in during difficulties. They freely support their partner in times of need. Using the metaphor of mother–

Recall that Bowlby and Ainsworth believe that the dance of attachment between the caregiver and baby is the basis for feeling securely attached in infancy and for dancing well in other relationships in life. If you listen to friends anguishing about their relationship problems, you will hear similar ideas: “The reason I act clingy and jealous is that, during my childhood, I felt unloved.” “It’s hard for me to warm up and respond to kisses because my mom was rejecting and cold.” We already know that attachment styles can change throughout childhood and adolescence (see Chapter 4). In fact, a better predictor of being securely attached in your twenties is not your attachment status during infancy, but maintaining close friendships as a teen (Fraley and others, 2013; Pascuzzo, Cyr, & Moss, 2013). Once entering adulthood, how much can attachment styles change from year to year?

To answer this question, researchers measured the attachment styles of several hundred women at intervals over two years (Cozzarelli and others, 2003). They found that almost one-

One reason attachment styles stay stable is that they may operate as a self-

By now, you are probably impressed with the power of the attachment-

Still, as a framework for understanding people (and ourselves), the attachment styles perspective has great appeal. Who can’t relate to having had a lover (or friend or parent) with a “dismissing” or “preoccupied” attachment? Don’t the defining qualities of secure attachment give us a beautiful roadmap for how we personally should relate to the significant others in our lives? Attachment theory allows us to look at every love relationship through a fascinating new lens.

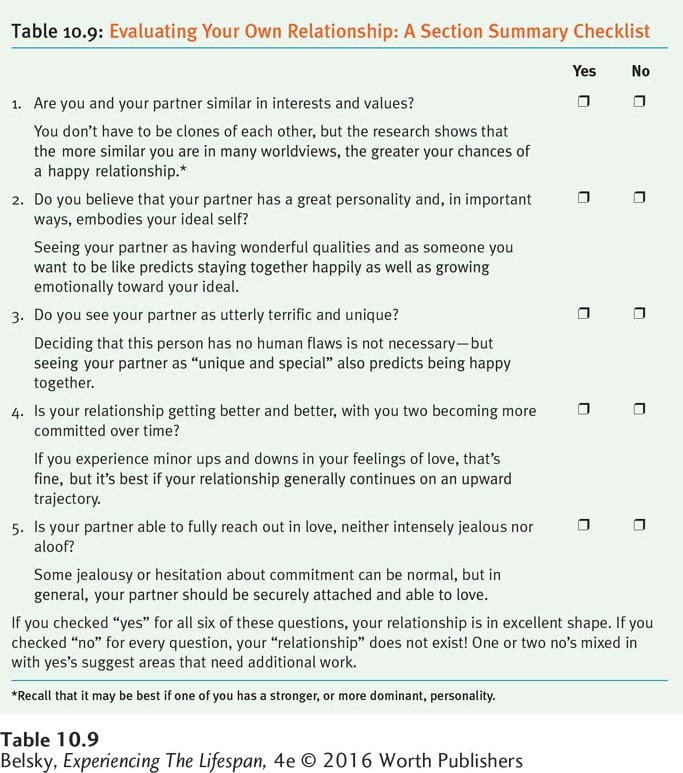

INTERVENTIONS: Evaluating Your Own Relationship

How can you use all of the insights in this section to ensure smoother-

So far, I have just begun my exploration into those adult agendas: love and work. In the next chapter, we’ll focus directly on that core adult love relationship—

Tying It All Together

Question 10.14

If Latoya is discussing with James how relationships have changed in recent decades, which two statements should she make?

There is now more interracial and interethnic dating.

Same-

sex relationships are now much more acceptable. Homophobia is now rare.

a and b

Question 10.15

Today, relatively few/many single people are open to Internet dating, and on-

Today many people are open to internet dating and on-

Question 10.16

Natasha and Akbar met at a friend’s New Year’s Eve party and just started dating. They are about to find out whether they share similar interests, backgrounds, and worldviews. This couple is in Murstein’s (choose one) stimulus/value-

value-

Question 10.17

Catherine tells Kelly, “To have a happy relationship, find someone as similar to you as possible.” Go back and review this section. Then list the ways in which Catherine is somewhat wrong.

Actually, people who have dominant personalities might be better off with more submissive mates (and vice versa). Respecting a partner’s personality is more important than being alike in every attribute and trait. Rather than searching for a clone, it’s best to find a mate who is similar to one’s ideal self. Overinflating that person’s virtues helps tremendously, too!

Question 10.18

Kita is clingy and always feels rejected. Rena runs away from intimate relationships. Sam is affectionate and loving. Match the attachment status of each person to one of the following alternatives: secure, avoidant-

Kita’s status is preoccupied. Rena is avoidant/dismissing. Sam is securely attached.