8.2 Body Image Issues

What do you daydream about?

—Amanda (quoted in Martin, 1996, p. 36)

Puberty is a time of intense physical preoccupations, and there is hardly a teenager who isn’t concerned about some body part. How important is it for young people to be generally satisfied with how they look?

Consider this finding: Susan Harter (1999) explored how feeling competent in each of her five “self-worth” dimensions—scholastic abilities, conduct, athletic skills, peer likeability, and appearance (recall Chapter 6)—related to teenagers’ overall self-esteem. She found that being happy about one’s looks outweighed anything else in determining whether adolescents generally felt good about themselves.

This finding is not just true of teenagers in the United States. It appears in surveys conducted in Western countries among people at various stages of life. If we are happy with the way we look, we are likely to be happy with who we are as human beings.

Feeling physically appealing is important to everyone—for boys, surprisingly, one study suggested, more than for girls (Mellor and others, 2010). But, girls (no surprise) are prone to be especially unhappy with their looks (Lawler and Nixon, 2011; Warren, Schoen, & Schafer, 2010). One reason for pervasive body dissatisfaction comes as no surprise—the intense cultural pressure to be thin.

The Differing Body Concerns of Girls and Boys

The distorting impact of the thin ideal, or pressure to be abnormally thin, was graphically suggested in an Irish survey. The researchers found that 3 out of 4 female teens with average BMIs felt they were too fat. An alarming percentage—2 out of 5—of underweight girls also wanted to shed pounds (Lawler & Nixon, 2011). While some boys (those who were genuinely heavy in this study, for instance) also worried about their weight, especially in our twenty-first century culture, males have another concern: They want to build up their muscles—spending hours at the gym, sometimes using dangerous anabolic steroids to increase their body mass (Parent & Moradi, 2011; Smolak & Stein, 2010).

When did our culture develop the idea that women should be unrealistically thin? Historians trace this change to the 1970s, when extremely slim actresses like Audrey Hepburn became our cultural ideal. More recently, as you can see in the second photo, similar body pressures have infected the other sex, causing this vulnerable eighth-grade boy to struggle to attain the muscled male shape that is our contemporary cultural ideal.

Flirt/Flirt/Superstock

Page 245

These preoccupations may be set in motion by biological forces. As you will see in the next chapter, the hormonal changes of puberty prime pre-teens to be unusually sensitive to social cues. New research suggests that the female obsession to be thin may have roots even before we emerge from the womb. In one incredible study, scientists found female twin pairs were more apt to develop unhealthy dieting practices at puberty than females in fraternal twin pairs where the other twin was male—suggesting that testosterone (given off by the male twin’s body) may dampen down the female tendency to become weight obsessed during the pubertal years (Culbert and others, 2013).

Still, even if the signal “be supersensitive to your body” is hormonal, outer-world pressures prime the pump: Pre-teens love to tease one another about weight (“Ha, ha, you are getting fat!”) (Compian, Gowen, & Hayward, 2004; Jackson & Chen, 2008; Lawler & Nixon, 2011). When children are already unhappy, this teasing can provoke an obsession with dieting—for either sex (Benas, Uhrlass, & Gibb, 2010; Hutchinson, Rapee, & Taylor, 2010).

A primary culprit is the media, for its regular drumbeat advocating the thin ideal. As early as preschool, one study showed, girls have internalized the message, “You need to be thin” (Harriger and others, 2010). Digitally altered images beamed from TV, the Internet, and magazines set body-size standards that are often impossible to attain (López-Guimerà and others, 2010). So it’s no wonder that being shown snapshots of ultra-thin women activates body dissatisfaction in temperamentally vulnerable teens and adults (Anschutz and others, 2011; Roberts & Good, 2010).

Interestingly, due to an epigenetic process, this fraternal twin girl may be more insulated from developing an eating disorder as a teen by simply being exposed to the circulating testosterone her brother’s body is giving off.

Anna Azimi/Shutterstock

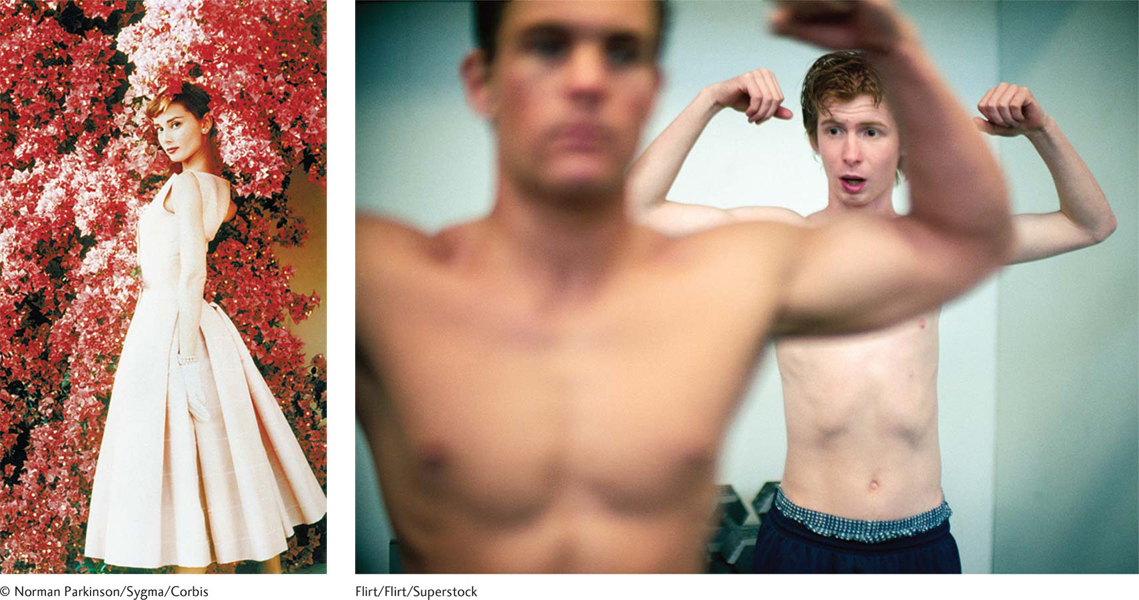

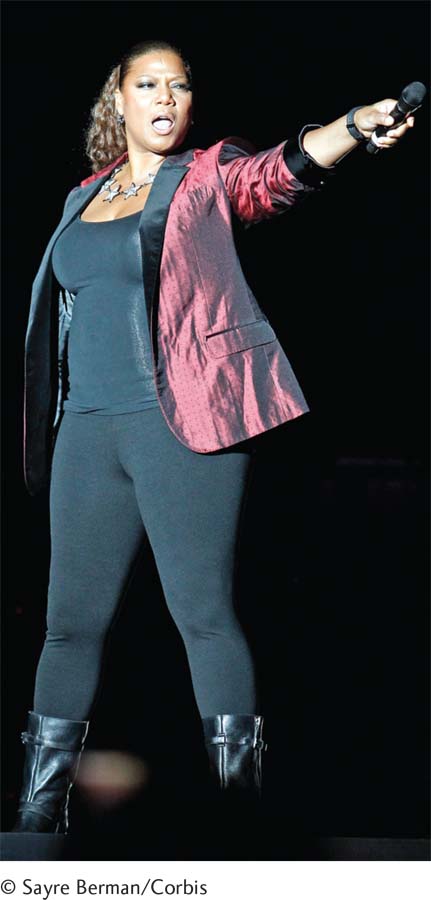

Still, some children are less susceptible to the media messages. In Albert Bandura’s social learning framework, for instance, African American and Latino girls should be more insulated from the thin ideal because their media role models, such as Queen Latifah and Beyonce, demonstrate that beauty comes in ample sizes. As one young African American woman in an interview study explained: “I feel like . . . for the woman of color . . . the look is like thick thighs, you know fat butt . . . (men) like, like want you to have meat on your body” (quoted in Hesse-Biber and others, 2010, p. 704).

Page 246

Does this mean that, unless they are obese, Latino and African American teens don’t worry about their weight? No! If an ethnic minority girl identifies with the mainstream, Western thin ideal, she is just as vulnerable to developing eating disorders as any other teen (Sabik, Cole, & Ward, 2010). What exactly are eating disorders like?

Queen Latifah embodies the fact that bodies are beautiful at every size. Not only is she a role model for women of color, but for every woman in our culture.

© Sayre Berman/Corbis

Eating Disorders

In the morning I’ll have a black coffee. At noon I have a mix of shredded lettuce, carrots and cabbage. At around dinnertime I have 9 mini whole-wheat crackers. On a bad day I may have. . . . with my (morning) black coffee an egg white, . . .

(adapted from Juarascio, Shoaib, & Timko, 2010, p. 402)

Scales are evil! But I’m obsessed with them! I’m on the damn thing like 3 times a day!

(adapted from Gavin, Rodham, & Poyer, 2008, pp. 327–328)

As these quotations from “pro-anorexia” social network sites show, eating disorders differ from “normal” dieting. Here, eating is the sole focus of life. Imagine waking up and planning each day around eating (or not eating). You monitor every morsel. You are obsessed with checking and rechecking your weight. Or you have the impulse to gorge every time you approach the refrigerator or buy a box of candy at the store. Let’s now explore three major forms these total food fixations take: anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder.

Anorexia nervosa, the most serious eating disorder, is defined by self-starvation—specifically to the point of being 85 percent of one’s ideal body weight or less. (This means that if 110 pounds is the ideal weight for your height, you would now weigh less than 95 pounds.) Another common feature of this primarily female disorder is that leptin levels have become too low to support adult fertility and the girl has stopped menstruating. A hallmark of eating disorders—among both girls and boys—is a distorted body image (Espeset and others, 2011). Even when people look skeletal, they feel fat. They often compulsively exercise, running miles for hours, abandoning their other commitments to spend every day at the gym (Holland, Brown, & Keel, 2014). They may be disconnected from reality, denying that their symptoms apply to them (“Oh no, I don’t binge and purge”) (Gratwick-Sarll, Mond, & Hay, 2013). Sometimes they literally don’t see their true body size: As one girl named Sarah commented: “I remember . . . passing an open door and saw myself in the mirror . . . and thought “Oh gosh, she is thin!” but then when I understood that it was actually me, I didn’t see me as thin anymore” (quoted in Espeset and others, 2011, p. 183).

Anorexia is a life-threatening disease. When people reach two-thirds of their ideal weight or less, they need to be hospitalized and fed—intravenously, if necessary—to stave off death (Diamanti and others, 2008). A student of mine who runs a self-help group for people with eating disorders provided a vivid reminder of the enduring physical toll anorexia can cause. Alicia informed the class that she had permanently damaged her heart muscle during her bout with this devastating disease.

Bulimia nervosa is typically not life threatening because the person’s weight often stays within a normal range. However, because this disorder involves frequent binging (at least once weekly eating sprees in which thousands of calories may be consumed in a matter of hours) and either purging (getting rid of the food by vomiting or misusing laxatives and diuretics) or fasting, bulimia can seriously compromise health. In addition to producing deficiencies of basic nutrients, the purging episodes can cause mouth sores, ulcers in the esophagus, and the loss of tooth enamel due to being exposed to stomach acid.

Binge eating disorder, which first appeared in the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) in 2013, involves recurrent out-of-control eating. The person wolfs down huge quantities of food and then is wracked by disgust, guilt, and shame. This mental disorder was added to the DSM-5 because (no surprise) it is intimately tied to obesity and so presents a serious threat to health (Myers & Wiman, 2014). Binge eating disorder, like anorexia and bulimia, can wreak enduring havoc on the person’s life (Goldschmidt and others, 2014).

Page 247

How common are these mainly female disorders, which most frequently erupt in the early twenties or late teens? In one eight-year-long community survey, binge eating disorder was most prevalent, affecting roughly 3 in 100 young women over that time; bulimia ranked second (at 2.6 in 100). Thankfully, the most serious condition, anorexia, struck only 8 out of a thousand girls. The bad news is that subclinical (less severe) forms of eating disorders may affect an astonishing 18 million people in the United States at some point in life (Forbush & Hunt, 2014).

A temperamental tendency to be anxious, low self-efficacy, a great need for approval, and the inability to express your legitimate needs. These poisonous forces, plus a commitment to the thin ideal, may have produced this child’s eating disorder. Moreover, because whenever she feels bad about herself, she automatically thinks, “I’m too fat”—self-starvation has become her main mode of dealing with stress.

Jamie Grill/The Image Bank/Getty Images

What causes these conditions? Twin studies suggest anorexia and bulimia have a hereditary component (Striegel-Moore & Bulik, 2007). One nonspecific risk factor is prior internalizing symptoms—a tendency during middle childhood to be anxious and depressed (Touchette and others, 2011). At puberty, if these “I hate myself” attitudes translate into a commitment to the thin ideal, an obsession with dieting or binge eating and purging can result (Espinoza, Penelo, & Raich, 2010; Stice, Ng, & Shaw, 2010).

Researchers find teens and young adults with eating disorders have other psychological symptoms: insecure attachments, an extreme need for approval (Abbate-Dega and others, 2010), or rigidity (Masuda, Boone, & Timko, 2011). They often have trouble expressing their needs (Norwood and others, 2011). One hallmark of eating disorders is incredibly poor self-worth, that is, feeling like a terrible human being (Fairchild & Cooper, 2010). At bottom, these teens have low self-efficacy—feeling out of control of their lives.

If a young person develops anorexia or bulimia, how do these feelings get channeled into an obsession with being too fat? Hints come from an experiment in which researchers told girls with an eating disorder and others a comparison group to think about an event in which they felt useless or incapable. After the “feeling incompetent” instructions, the girls with an eating disorder automatically focused on their body flaws (McFarlane, Urbszat, & Olmsted, 2011). So when girls are temperamentally prone to low self-esteem and believe that the key to happiness is being ultrathin, negative emotions may be displaced into feeling “I’m too fat,” and warded off by extreme measures to control one’s weight.

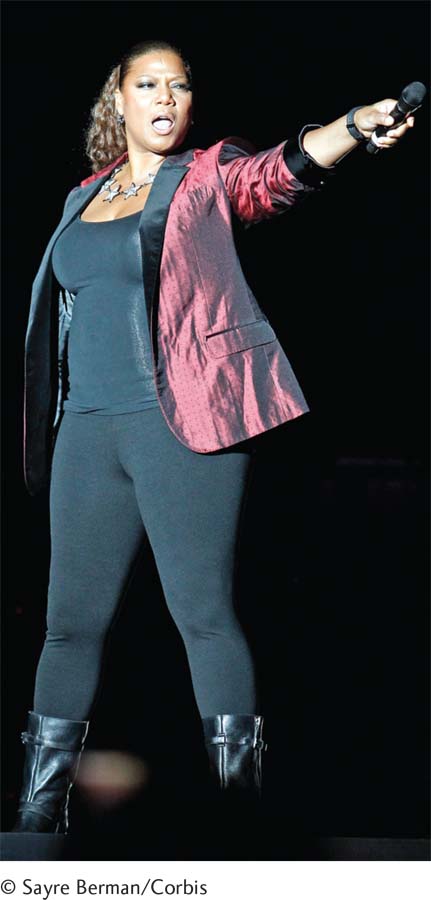

Table 8.2 offers a summary checklist for determining if a teenager you love is at risk for serious body dissatisfaction. Still, if you know a young person who is struggling with an eating disorder, there is brighter news. Most adolescents grow out of eating problems as they get older and construct a satisfying adult life (Keel and others, 2007). Moreover, contrary to popular opinion, therapy for eating disorders works!

Page 248

INTERVENTIONS: Improving Teenagers’ Body Image

Perhaps the first place to begin to treat young people with eating disorders is to examine how girls who embrace their bodies reason and think. As one interview study suggested, these teens do not deny their “imperfections,” but they discount negative comments and focus on their physical pluses. Yes, they do care deeply about their looks, but they view being beautiful as taking care of their physical health—eating nutritious foods, exercising, appreciating what their bodies can do (Frisén & Holmqvist, 2010). These adolescents are often spiritually oriented (Boisvert & Harrell, 2013). They understand what really makes people beautiful in life. As one woman named Heather put it: “You have to remind yourself that even though (the thin ideal) is what (the media are) . . . promoting, self-esteem really looks the best” (Wood-Barcalow, Tylka, & Augustus-Horvath, 2010, p. 115).

Heather’s remarks explain why a popular eating-disorder treatment (called dialectic behavior therapy) teaches meditation, as well as strategies to promote self-efficacy (feeling in control of one’s life) (Lenz and others, 2014). Therapists have devised other creative approaches, such as repeatedly exposing women to video images of themselves, to train them to see their real body size (Trentowska, Svaldi, & Tuschen-Caffier, 2014).

One innovative therapy ignores any underlying psychological causes. Arguing that eating disorders are totally biologically based, therapists have had success by keeping the girl’s body temperature warm and training her in the appropriate amount to eat via a scale under a plate that measures her intake (Bergh and others, 2013).

While, as I just mentioned, eating disorders have the reputation of being hard to cure, the reverse seems true. This may explain why therapists who treat these young people have lower burnout rates than do their colleagues (Thompson-Brenner, 2013; Warren and others, 2013) and find such personal meaning in this work (Zerbe, 2013).

The same upbeat message is typical of much (but not all) of the research relating to our final topic: teenage sex.