11.4Lectins Are Specific Carbohydrate-Binding Proteins

Lectins Are Specific Carbohydrate-Binding Proteins

The diversity and complexity of the carbohydrate units and the variety of ways in which they can be joined in oligosaccharides and polysaccharides suggest that they are functionally important. Nature does not construct complex patterns when simple ones suffice. Why all this intricacy and diversity? It is now clear that these carbohydrate structures are the recognition sites for a special class of proteins. Such proteins, termed glycan-

334

Lectins promote interactions between cells

Cell–

We have already met a lectin obliquely. Recall that, in I-

Lectins are organized into different classes

Lectins can be divided into classes on the basis of their amino acid sequences and biochemical properties. One large class is the C type (for calcium-

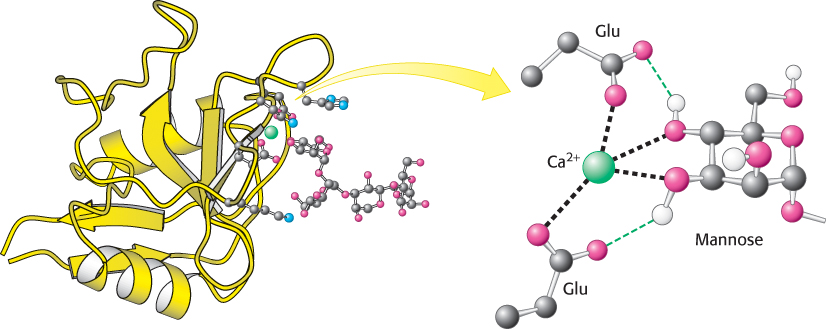

FIGURE 11.30 Structure of a carbohydrate-

FIGURE 11.30 Structure of a carbohydrate-A calcium ion on the protein acts as a bridge between the protein and the sugar through direct interactions with sugar OH groups. In addition, two glutamate residues in the protein bind to both the calcium ion and the sugar, and other protein side chains form hydrogen bonds with other OH groups on the carbohydrate. The carbohydrate-

335

Proteins termed selectins are members of the C-

Another large class of lectins comprises the L-lectins. These lectins are especially rich in the seeds of leguminous plants, and many of the initial biochemical characterizations of lectins were performed on this readily available lectin. Although the exact role of lectins in plants is unclear, they can serve as potent insecticides. Other L-type lectins, such as calnexin and calreticulin, are prominent chaperones in the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum. Recall that chaperones are proteins that facilitate the folding of other proteins.

Influenza virus binds to sialic acid residues

Many pathogens gain entry into specific host cells by adhering to cell-

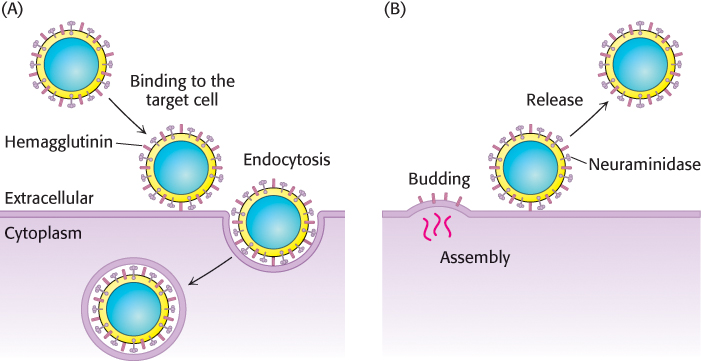

Many pathogens gain entry into specific host cells by adhering to cell-

After binding hemagglutinin, the virus is engulfed by the cell and begins to replicate. To exit the cell, a process essentially the reverse of viral entry occurs (Figure 11.31B). Viral assembly results in the budding of the viral particle from the cell. Upon complete assembly, the viral particle is still attached to sialic acid residues of the cell membrane by hemagglutinin on the surface of the new virions. Another viral protein, neuraminidase (sialidase), cleaves the glycosidic bonds between the sialic acid residues and the rest of the cellular glycoprotein, freeing the virus to infect new cells, and thus spreading the infection throughout the respiratory tract. Inhibitors of this enzyme such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are important anti-

336

Viral hemagglutinin’s carbohydrate-

Plasmodium falciparum, the parasitic protozoan that causes malaria, also relies on glycan binding to infect and colonize its host. Glycan-