28.2DNA Unwinding and Supercoiling Are Controlled by Topoisomerases

DNA Unwinding and Supercoiling Are Controlled by Topoisomerases

As a helicase moves along unwinding DNA, the DNA in front of the helicase will become overwound in the absence of other changes. As discussed in Section 4.2, DNA double helices that are torsionally stressed tend to fold up on themselves to form tertiary structures created by supercoiling. We will first consider the supercoiling of DNA in quantitative terms and then turn to topoisomerases, enzymes that can directly modulate DNA winding and supercoiling. Supercoiling is most readily understood by considering circular DNA molecules, but it also applies to linear DNA molecules constrained to be in loops by other means. Most DNA molecules inside cells are subject to supercoiling.

834

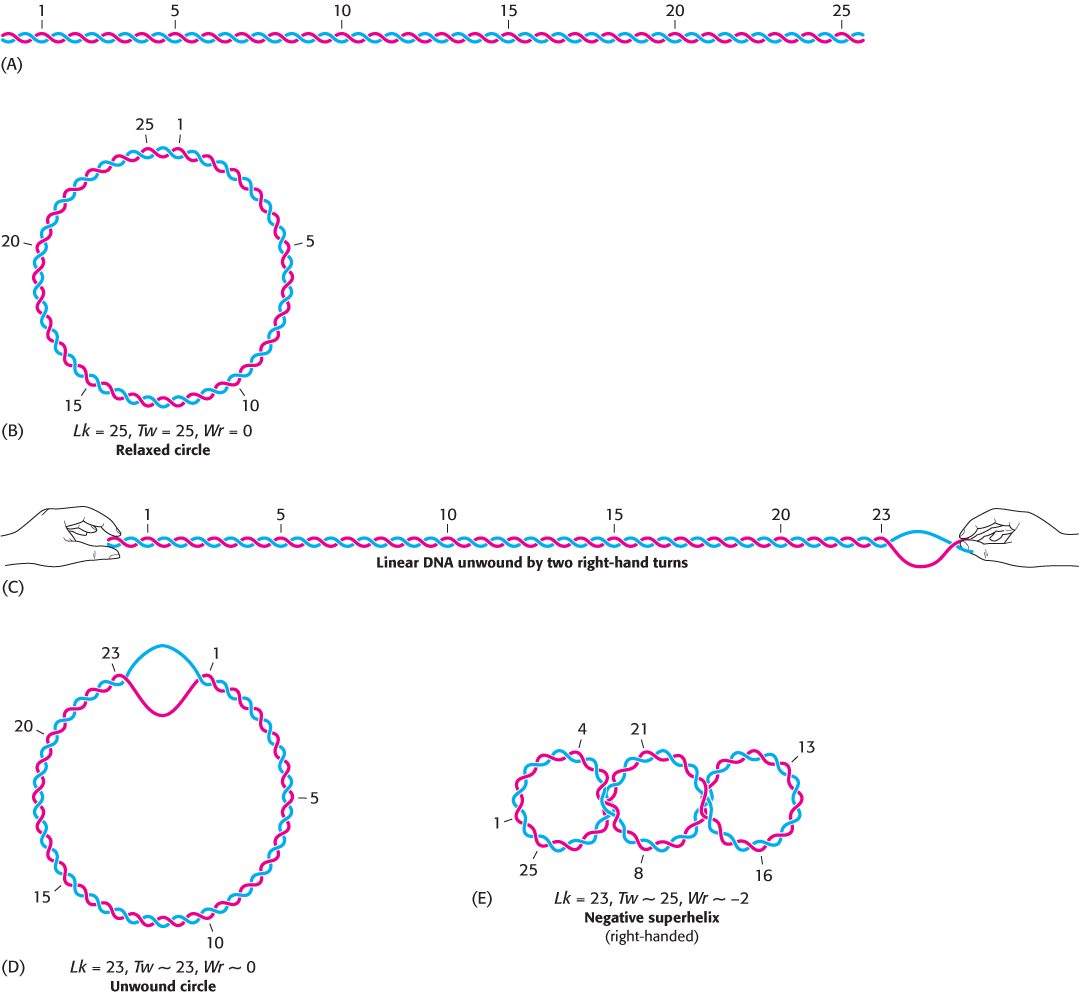

Consider a linear 260-

835

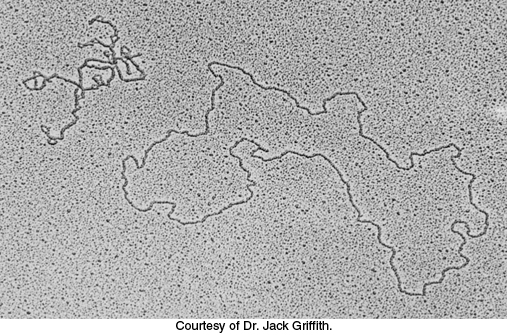

Supercoiling markedly alters the overall form of DNA. A supercoiled DNA molecule is more compact than a relaxed DNA molecule of the same length. Hence, supercoiled DNA moves faster than relaxed DNA when analyzed by centrifugation or electrophoresis. Unwinding will cause supercoiling in circular DNA molecules, whether covalently closed or constrained in closed configurations by other means.

The linking number of DNA, a topological property, determines the degree of supercoiling

Our understanding of the conformation of DNA is enriched by concepts drawn from topology, a branch of mathematics dealing with structural properties that are unchanged by deformations such as stretching and bending. A key topological property of a circular DNA molecule is its linking number (Lk), which is equal to the number of times that a strand of DNA winds in the right-

The unwound DNA and supercoiled DNA shown in Figure 28.15D and E are topologically identical but geometrically different. They have the same value of Lk but differ in twist (Tw) and writhe (Wr). Although the rigorous definitions of twist and writhe are complex, twist is a measure of the helical winding of the DNA strands around each other, whereas writhe is a measure of the coiling of the axis of the double helix—

Is there a relation between Tw and Wr? Indeed, there is. Topology tells us that the sum of Tw and Wr is equal to Lk.

In Figure 28.15, the partly unwound circular DNA has Tw ~ 23, meaning the helix has 23 turns and Wr ~ 0, meaning the helix has not crossed itself to create a supercoil. The supercoiled DNA, however has Tw ~ 25 and Wr ~ −2. These forms can be interconverted without cleaving the DNA chain because they have the same value of Lk—namely, 23. The partitioning of Lk (which must be an integer) between Tw and Wr (which need not be integers) is determined by energetics. The free energy is minimized when about 70% of the change in Lk is expressed in Wr and 30% is expressed in Tw. Hence, the most stable form would be one with Tw = 24.4 and Wr = −1.4. Thus, a lowering of Lk causes both right-

836

Topoisomerases prepare the double helix for unwinding

Most naturally occurring DNA molecules are negatively supercoiled. What is the basis for this prevalence? As already stated, negative supercoiling arises from the unwinding or underwinding of the DNA. In essence, negative supercoiling prepares DNA for processes requiring separation of the DNA strands, such as replication. Positive supercoiling condenses DNA as effectively, but it makes strand separation more difficult.

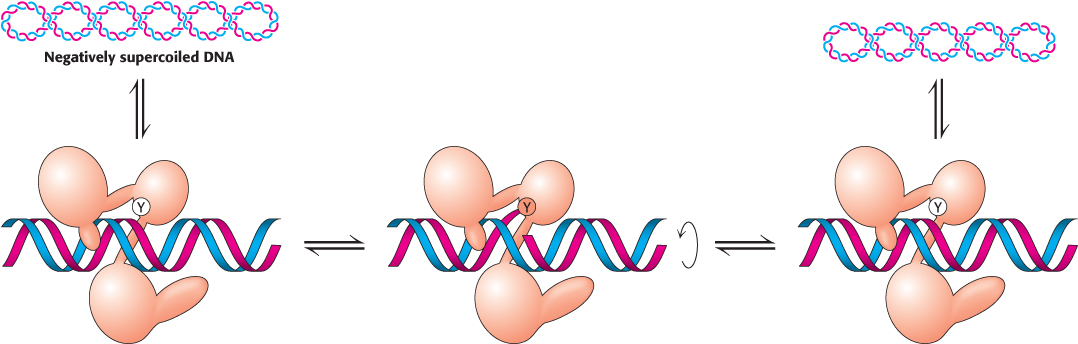

The presence of supercoils in the immediate area of unwinding would, however, make unwinding difficult. Therefore, negative supercoils must be continuously removed, and the DNA relaxed, as the double helix unwinds. Specific enzymes called topoisomerases that introduce or eliminate supercoils were discovered by James Wang and Martin Gellert. Type I topoisomerases catalyze the relaxation of supercoiled DNA, a thermodynamically favorable process. Type II topoisomerases utilize free energy from ATP hydrolysis to add negative supercoils to DNA. Both type I and type II topoisomerases play important roles in DNA replication as well as in transcription and recombination.

These enzymes alter the linking number of DNA by catalyzing a three-

Type I topoisomerases relax supercoiled structures

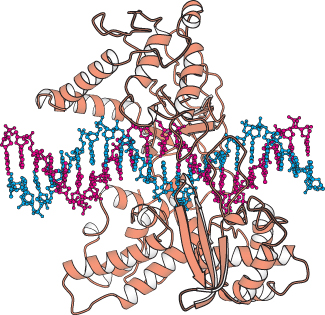

FIGURE 28.17 Structure of topoisomerase I. The structure of a complex between a fragment of human topoisomerase I and DNA is shown. Notice that DNA lies in a central cavity within the enzyme.

FIGURE 28.17 Structure of topoisomerase I. The structure of a complex between a fragment of human topoisomerase I and DNA is shown. Notice that DNA lies in a central cavity within the enzyme.

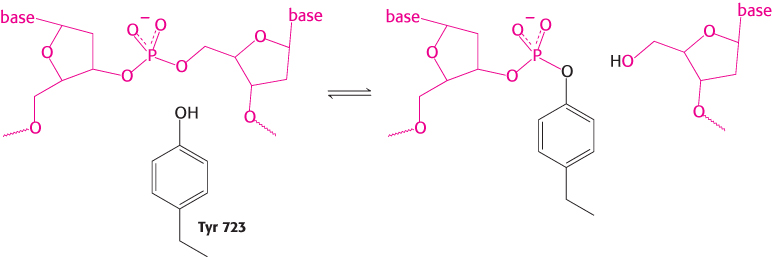

The three-

837

From analyses of these structures and the results of other studies, the relaxation of negatively supercoiled DNA molecules is known to proceed in the following manner (Figure 28.18). First, the DNA molecule binds inside the cavity of the topoisomerase. The hydroxyl group of tyrosine 723 attacks a phosphoryl group on one strand of the DNA backbone to form a phosphodiester linkage between the enzyme and the DNA, cleaving the DNA and releasing a free 5′-hydroxyl group.

With the backbone of one strand cleaved, the DNA can now rotate around the remaining strand, its movement driven by the release of energy stored because of the supercoiling. The rotation of the DNA unwinds the supercoils. The enzyme controls the rotation so that the unwinding is not rapid. The free hydroxyl group of the DNA attacks the phosphotyrosine residue to reseal the backbone and release tyrosine. The DNA is then free to dissociate from the enzyme. Thus, reversible cleavage of one strand of supercoiled DNA allows controlled rotation to partly relax the supercoils.

Type II topoisomerases can introduce negative supercoils through coupling to ATP hydrolysis

Supercoiling requires an input of energy because a supercoiled molecule, in contrast with its relaxed counterpart, is torsionally stressed. The introduction of an additional supercoil into a 3000-

838

Supercoiling can be catalyzed by type II topoisomerases. These elegant molecular machines couple the binding and hydrolysis of ATP to the directed passage of one DNA double helix through another, temporarily cleaved DNA double helix. These enzymes have several mechanistic features in common with the type I topoisomerases.

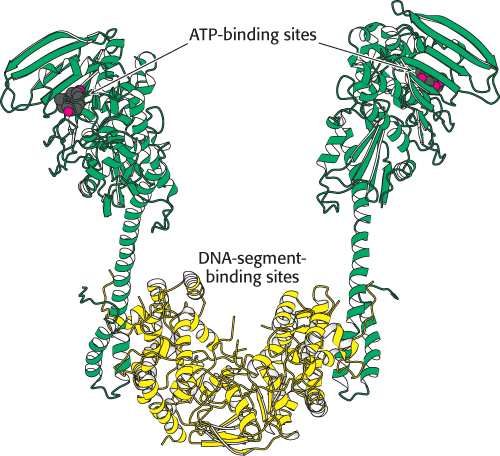

FIGURE 28.19 Structure of topoisomerase II. The dimeric structure of a typical topoisomerase II, that from the archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae. Notice that each half of the enzyme has one domain (shown in yellow) that contains a region for binding a DNA double helix and another domain (shown in green) that contains ATP binding sites.

FIGURE 28.19 Structure of topoisomerase II. The dimeric structure of a typical topoisomerase II, that from the archaeon Sulfolobus shibatae. Notice that each half of the enzyme has one domain (shown in yellow) that contains a region for binding a DNA double helix and another domain (shown in green) that contains ATP binding sites.

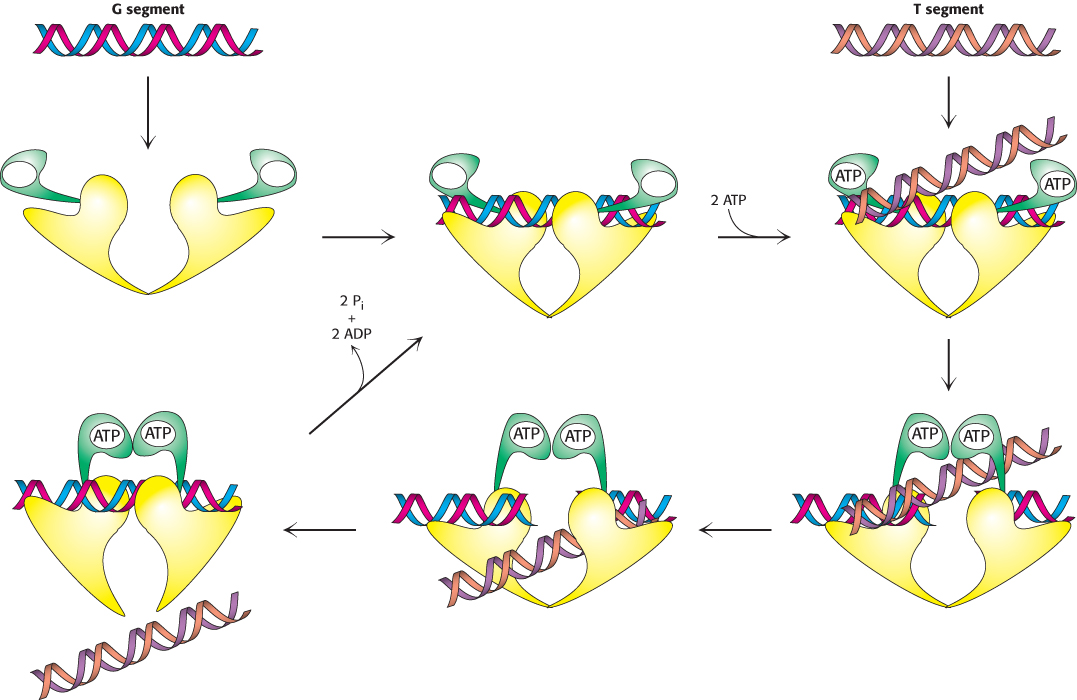

Topoisomerase II molecules are dimeric with a large internal cavity (Figure 28.19). The large cavity has gates at both the top and the bottom that are crucial to topoisomerase action. The reaction begins with the binding of one double helix (hereafter referred to as the G, for gate, segment) to the enzyme (Figure 28.20). Each strand is positioned next to a tyrosine residue, one from each monomer, capable of forming a covalent linkage with the DNA backbone. This complex then loosely binds a second DNA double helix (hereafter referred to as the T, for transported, segment). Each monomer of the enzyme has a domain that binds ATP; this ATP binding leads to a conformational change that strongly favors the coming together of the two domains. As these domains come closer together, they trap the bound T segment. This conformational change also forces the separation and cleavage of the two strands of the G segment. Each strand is linked to the enzyme by a tyrosine–

839

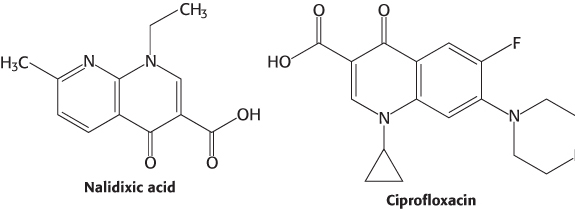

The bacterial topoisomerase II (often called DNA gyrase) is the target of several antibiotics that inhibit the prokaryotic enzyme much more than the eukaryotic one. Novobiocin blocks the binding of ATP to gyrase. Nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin, in contrast, interfere with the breakage and rejoining of DNA chains. These two gyrase inhibitors are widely used to treat urinary tract and other infections including those due to Bacillus anthracis (anthrax). Camptothecin, an antitumor agent, inhibits human topoisomerase I by stabilizing the form of the enzyme covalently linked to DNA.

The bacterial topoisomerase II (often called DNA gyrase) is the target of several antibiotics that inhibit the prokaryotic enzyme much more than the eukaryotic one. Novobiocin blocks the binding of ATP to gyrase. Nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin, in contrast, interfere with the breakage and rejoining of DNA chains. These two gyrase inhibitors are widely used to treat urinary tract and other infections including those due to Bacillus anthracis (anthrax). Camptothecin, an antitumor agent, inhibits human topoisomerase I by stabilizing the form of the enzyme covalently linked to DNA.